TAR-BABY

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

Ron Stahl

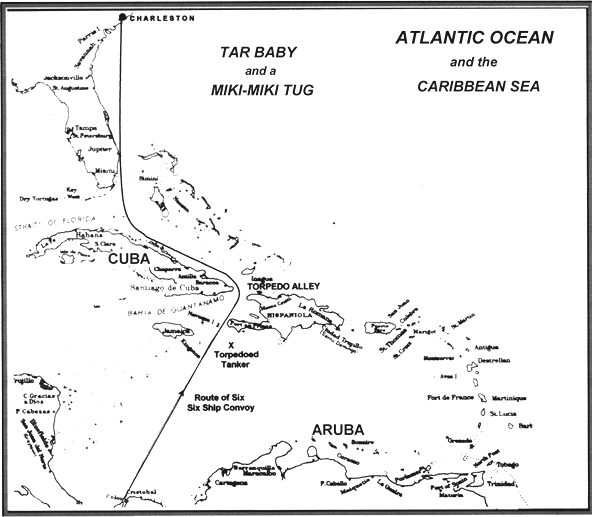

We were steaming at a good clip for a seven ship convoy, originating out of Christobal, Canal

Zone. Our greatest fear lay ahead at the 60 mile gap between Cuba and Haiti, named the Windward Passage but better known by merchant seamen as the beginning of “Torpedo Alley”.

The afternoon of our third day out was miserable; the wind freshened to 20-30 knots and the seas were coming over our starboard rails. We couldn’t maintain the pace or the course, so our Captain informed the convoy leader, by blinker light, that we must adjust our heading and reduce speed for our ships safety.

The afternoon of our third day out was miserable; the wind freshened to 20-30 knots and the seas were coming over our starboard rails. We couldn’t maintain the pace or the course, so our Captain informed the convoy leader, by blinker light, that we must adjust our heading and reduce speed for our ships safety.

Of the six other ships, four resembled C-1s and C-2s, one was an old tanker, and one a passenger vessel of the type that plied the waters of Puget Sound. We were just a 127 foot ocean going wooden MIKI-MIKI type tug, en route from San Francisco, to be delivered to Brooklyn, New York for the Army Transportation Service, with a crew of fourteen men aboard.

After receiving permission to withdraw from the convoy we changed course to a more easterly direction to take on the large seas at a quarterly approach, and at a reduced speed hoping to come into the lee of Haiti during the coming evening. We also started monitoring the radio more seriously since we were now on our own.

On the 4-8 watch we heard a Mayday distress call, coming in over the radio, giving his position some 30 miles to the south of our position. We could hear a dog barking in the background. The poor fellow was trying to tell the name of his ship but all we could hear that was recognizable was something that sounded like “Point Saint Cir”. He kept repeating his latitude and longitude coordinates but he kept mixing them up. He said they were hit in the engine room at the stern with a torpedo and that they were two days out of Aruba.

We changed our course and with all the speed we could muster, dashed toward the area mentioned, when another radio broadcast came through warning all vessels to disregard the previous Mayday.

They explained it as a hoax by enemy subs to lure unsuspecting single traveling vessels into a trap, only to be attacked and sunk.

Our skipper had suffered wounds at the outset of the war from German aircraft bombing in the Mediterranean. His wounds had healed to the extent that he could return to coastwise duty; hence his assignment to our ship as a delivery Captain.

His reaction to the recall announcement was displayed by cursing the idiots on the radio and stamping his feet on the deck, pacing back and forth in the wheelhouse. “Can’t those idiots tell that the call was authentic? Didn’t they hear that dog barking in the background? No way they’d have a dog aboard a sub.”

The Captain was almost in a state of frenzy. He turned to me and shouted an order to steer a particular course, then blew into the engine room voice tube to raise the Engineers (he blew so hard you could hear the whistle even above the storm outside). “Can you get anything more out of her?…I want all she’s got!”

We were diving into each swell, and anything not secured was thrown from one end of the bridge to the other. Thank God I had the wheel to hang onto. Forget trying to steer a compass course, it was gimbaling all over the place. Just an occasional reference of our heading as the magnetic compass card spun from one direction to the other, no gyro compass nor power steering on this ship….manual only.

One moment the wheel would spin nice and easy, a moment later it took every muscle you had to turn it. As the bow dug into the oncoming swells the stern would lift out of the sea, the ship would shake and shudder as the props would spin free out of the water. This went on for three hours and the wheelhouse was filled with everyone aboard ship who were off watch.

Lookouts were stationed on the widows-walk and boat deck. Someone spotted a flicker of light ahead off in the distance. I adjusted my course and we traveled a good half hour before we could make out what the light was. From a distance you could just make out the lines of a ship awash, with her bridge house and bow above water. The seas around her had scattered groups of fires but the wind blew the patches of oil away from the ship even though she was still spilling her guts out.

We spotted a life boat and a raft tied together. We took aboard twelve poor souls covered with heavy molasses like goop all over them. The heavy seas were calmed by the oil laden water. We scoured the whole area, circling the tanker, everywhere we thought we saw something. We would drift with our engines shut down, to listen for any hailing and were about to give up the search when we heard what sounded like a dog barking near the sinking ship. A life ring with a man….and a little dog was on top of him barking like crazy. Both were covered with this black tar-like goop. As we brought them aboard we found the man was already dead.

We stayed as long as we could but many of the survivors needed medical attention, so we made a down-hill run for Jamaica which, considering the weather, was the fastest and closest opportunity for assistance. The crew of the sunken ship was English and the ship was British registered. Of the twenty brought aboard our ship, only sixteen later survived. The crew estimated twelve were killed outright in the initial blast, because it happened at the change of watch with two crews in the engine room at the same time. The blast knocked out the generators, pumps, and steam smothering system, making it impossible to try to fight the fires and save the ship.

On the way to Kingston we tried to clean the tar from the men using Diesel oil and kerosene….nothing seemed to work until the cook tried lard. It not only cleaned but it soothed the burns, not just the fire burns but the tar had an acid that was irritating the skin.

After getting off watch I helped where I could. The mess area was jam-packed with people; injured and those trying to help clean them up. After a while I went aft to the towing-winch house just to relax, when I heard a whimpering from under the towing engine. I had forgotten all about the dog. I started talking softly to it and reached in and pulled the little tar-ball out from under the machinery. It was a she-dog, only the eyes and mouth distinguished it from a pile of tar soaked rags.

I babied her and tried to clean her up. I tried everything I could think of to get the black stuff off her until I realized that her fur coat was naturally jet black. All the while I felt guilty doing for an animal when men in need of this same attention were lying on the galley decks. She must have swallowed a lot of oily water, for she kept dry-heaving and shivering uncontrollably. She was about the size of an over-grown cat, similar to a Boston Terrier, short hair, two pointy ears, one drooped down with a chunk missing (lost in a fight no doubt) and the other stood straight up at attention. I got a cup of water, a can of cream and the makings for a sandwich, but she just picked at the stuff.

The weather moderated, not near as much wind, and as we traveled down-wind with the following seas it gave a feeling of a gentle swaying motion that would put any man to sleep, especially after standing two four hour watches with another coming up in two hours. So I laid down in the winch compartment deck with the dog (I called her TAR-BABY) curled in my arms and we must have both fell sound asleep.

The mutt formed an attachment for me, it tried to follow me everywhere, even when I went on watch. She couldn’t climb the ladder to the wheel-house so she whined for me to carry her up.

Late the next morning we pulled into Kingston, Jamaica flying the “Quarantine” pratique flag along with the “Need Medical Assistance” flag, requesting a pilot to take us in to a dock. It turned out to be quite a fiasco. Sunday morning working people do not function at their best, especially when subordinates are in charge and the command set is at church or preparing for tea.

We blinked our needs to a tower at the entrance of the harbor but they misinterpreted our call for help as having a deadly disease aboard. The Harbor-Master came out in his shiny motor launch but wouldn’t get close enough to communicate by voice, he wanted to communicate by blinker light only. We finally got through to them that we had survivors from a British ship, and that they were in need of immediate assistance. Once our situation became clear to them they came from every direction and couldn’t do enough for us or be more hospitable.

We were led to a dock where a crowd started congregating. Many were in their Sunday-go-to-meeting clothes but that didn’t slow them down when it came to lending assistance where they could, helping to off load our unfortunate passengers into ambulances, trucks and automobiles. Every time a stranger stepped aboard, “Tar Baby” would bark a string of staccato yelps and at the same time kick back about two inches with each bark. She was all bark but no bite.

Some English officers came aboard and requested a briefing of the events with our crew, and to a man the story was the same….had that dog not barked over the radio there would not have been any survivors, based on the U.S. Navy=s order to disregard that MAYDAY transmission.

It broke my heart to make her go ashore with her own crew but she belonged with them and they assured us that she would be well provided for.