THE F BOATS

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

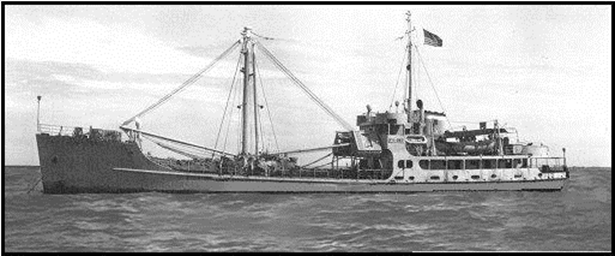

They were called by many names, F’s, FP’s, FS’s, AKA’s. Every branch of the armed services, including the Army, Navy, Coast Guard and even the Army Air Corps, had large numbers of them. Do you remember the USS Pueblo or the ship in the movie “Mr. Roberts”? What sleek little freighters they were, ideal for inter-island duty.

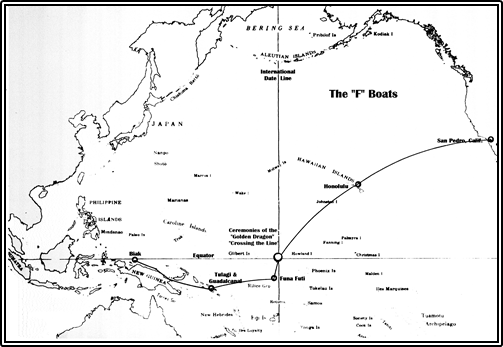

I joined my first FS boat at Wilmington, California in October, 1944, almost one year from the time I signed on the Miki-Miki tug out of the same office. Because of my previous towboat experience my first duty was to assist rigging up a towing arrangement for a wooden 85′ high speed QS boat to the South Pacific.

Prior to leaving on our trip a mate asked me to inspect and change, if necessary, all the black-out lights. The lights were just inside the entry hatches from the weather decks (these lights came on when as all the other lights went off when a door or hatch was opened, so we wouldn’t show any lights to the enemy subs). There were so many bulbs to prepare that I decided to set up a production line to paint them. I strung out a string of twenty bulbs tied so they would hang down, and then, by dipping them in a coffee can of what I thought was dark blue lacquer, they would dry hanging in place. That evening I replaced all the bulbs and waited for dark to put them to the test.

Men were in the mess playing cards when I decided to try the lights out. I opened the door; the overhead lights went out….but not even a hint of a faint blue light. I thought the switch gave out so I fiddled with that, but to no avail. All the while I was getting razzed for interrupting their card games. I tried another bulb, same thing, but I did see a hint of light near the socket. I scraped some of the lacquer off the bulb. I had indeed made blackout lights. In fact, they were so good no one could see the lights! Since, I had used all the spare bulbs in inventory. I found out that once black lacquer sets it’s very hard to scrape it off a fragile light bulb.

We left in a convoy of three similar ships, a Coast Guard FP which was a sister ship to us, and another FS belonging to the Army Air Corps which was modified to be a small aircraft repair vessel. Both the FP and our FS were towing QS boats. The other, a flush deck FS did not, as she was the convoy leader. All vessels except the Coast Guard were manned with Army Transport Service civilian seamen.

About six hours into the trip, we were notified by blinker light that the Engineer on the QS we were towing had crushed his foot while trying to secure the propeller shafts from turning. The message indicated that it looked very serious and that they couldn’t control the injured man’s bleeding.

Our Captain, after conferring with the convoy leader, ordered us to start retrieving the towing wire. We slowed just enough to maintain headway and then lowered our whale boat to pick up the injured man and take him to the Coast Guard FP, as they had a hospital corpsman aboard. Unable to adequately tend to the injury without surgery, the corpsman recommended returning the man to a hospital ashore.

Our QS tow was now under her own power maintaining her position with the rest of the ships. It was decided that the QS, being a fast boat, should return to port with the injured man and that we would continue at a slow pace, awaiting their return. The other ships were to go on at a reduced speed in hopes that we could catch up with them later.

The transfers were made from the Coast Guard FP to the QS. We then took aboard our whaleboat and watched the rest of the ships take off towards Hawaii.

A QS with her two 1500 HP gasoline engines could normally get up and plane at seventeen knots with a flank speed of about twenty-four knots, so we figured on four to five hours for her to make the trip to port and back if no problems arose. We were not disappointed. About six hours later we saw the QS on the horizon, and a short while later we were hooked up and chasing after our convoy. We caught up with them the next day.

The only other problem encountered on the trip was on our approach to the Hawaiian Islands. The seas were estimated to be running about 30 feet and the QS, because of her flat hull and the drag of the towing wire pulling her along, would surf almost up to us, and then as we started on the sleigh ride you could see the wire come taught and snap the QS’s bow around with a tremendous jerk. We finally told her to cast off the wire and go in under her own power.

Of about twelve QS’s towed across, our tow was one of the few boats that didn’t burn up the bearings in the engine or gear box, for most of the other QS’s did not clamp-lock their shafts as ours had. Most of the other boats just engaged the clutches to stop the spinning and burned up the engine bearings, as the lube oil pumps worked only with the engines running.

We spent a great liberty week in Honolulu. The storm that created the huge seas on our arrival was battering the north coasts of Oahu. We drove up to Waimea on an alligator truck that the Air Force repair ship had stowed on her deck, and watched the monstrous waves form way out, and then come pounding onto the beaches. I had never seen such action before, not even at the California beaches where I grew up.

We left Hawaii still towing the QS boat, with the flush deck FS boat as escort. The Coast Guard FP boat remained behind. Many years have elapsed so now admitting to a slight alteration in our primary course shouldn’t disturb anyone, but we did alter our course to cross both fences of where the 180th meridian and the Equator meet….and at 12 o’clock noon. Not many can claim that! (For whatever “THAT” is worth.)

Funa Futi, a tiny speck just off the Equator, was our destination. After arriving at the atoll we found it hard to believe that this had been a major base just a short time before. The island’s dimensions were something like three quarters of a mile by just a few hundred yards wide. Several smaller islands nearby had a few palms and bushes but no sign of life.

While looking for anchorage at Iron Bottom Bay, just off the coast of Guadalcanal, a comical scene developed, at my expense. After several attempts to take lead soundings (to determine the depth of the water) and ending in failure each time, the Captain asked me to show the seamen how it’s supposed to be done. The men either hadn’t been throwing the lead out ahead far enough or allowed it to cross the bows. I swung the lead in large arc and then with a mighty heave the lead weight took off on a beautiful flight as all the line trailed out behind, I just stood there… watching as the bitter-end of the lead-line followed and disappear into the sea! Naturally, not a spare could be found. The Captain expressed his admiration for my skills by congratulating me over the P.A. system, loud and clear for all to hear.

We refueled over at Tulagi and were on our way again. Our orders were to deliver the QS boat to Biak. The Air Force FS went on ahead. She could do twelve knots and we were lucky to get eight knots, besides their ship was needed up at the war area around Northern Luzon in the Philippines.

While anchored in the little bay of Biak, surrounded by a coral reef, a lone Japanese bomber followed a C-54 in to the landing strip, shot the transport plane down, and dropped about five Daisy-cutter bombs on the Air Transport Command quarters, killing many pilots and wounding several hundred people. (A Daisy-cutter is a bomb that is scored much like a hand-grenade, with deep criss-cross patterns on the shell. The bomb is fused to explode about 50 feet above the ground and will cut foliage, people and structures to shreds.)

Everyone aboard ship rushed topside after feeling the concussion of the bomb blasts. I was on anchor watch and rushed to the bow to either trip the pin at the bitter end and slip the chain, or begin raising the anchor on orders from the bridge. Finally, a full two minutes after the bomb blasts, three red tracers were shot into the sky and a few minutes’ later three white tracers were fired and the all clear was sounded. Unfortunately my watch Officer, while trying to prepare the windlass to take in the anchor chain, dropped the clutch bar in the wildcat and gear assembly. He had to extend his body reaching for the bar, lost his balance, and fell among the gears. Several ships in the immediate area already had their lights on, so I used my flashlight to assist the mate and also to try to locate the clutch bar. All of a sudden I felt a hard pressure against my head and a startling order to “Shut that dammed light off or I’ll blow your head off”. The Captain was holding a .45 caliber automatic pistol against my head. I dropped the light and it fell into the winch mechanism still shining bright. I fell flat on the deck, afraid that any minute I’d be shot.

I was placed under arrest and confined to the pantry. During the night the entire crew came by to wish me luck. The next morning I was taken ashore and charges of “Insubordination” were filed. An Army officer asked for my version of the events and I told him to go and talk to the mate I was on watch with.

The Army officer interviewed some of the crew and concluded that the problem was attributed to a malfunction of the PA system. The captain had repeatedly broadcast orders over the PA to all of us who were standing ready at the anchor winch. Receiving no response to his orders, the Captain thought we were ignoring him. He just blew his stack, came charging off the bridge, stumbled over gear on the deck, and the flashlight was just another element to enrage him. An understanding of sorts was made, but I felt I wouldn’t feel comfortable sailing with him. I requested a transfer and wound up serving the rest of the war out in the back waters of the South Pacific along the New Guinea coast and the islands of the Southern Philippines.

A call was put out for blood transfusions. They even offered fresh eggs, any style, to all who would donate. Who could resist! While I was donating blood a group of entertainers attached with the Bob Hope tour, en-route to their next performance, were in the medical compound also giving blood. They volunteered to give a special performance to all who donated blood. What a show….What a group….and what a crowd!

I was assigned as skipper of an MTL (46′ motor tow launch) used to ferry crews back and forth to their ships. The harbor master also used it to inspect vessels in the harbor. We had an LCM and a small wooden ST in our little fleet, and I was having a ball because everyone wanted to go on my MTL instead of the other boats. I had a cot and mosquito bar, for sleeping aboard, but it was too hot and too much trouble to fold up the cot and stow it away every morning. I was instructed to bivouac at an infantry camp just a short distance from my boat dock. I slept, showered, and ate there, and met some great guys who later saved my life.

A good movie was showing at a Quarter-master camp on another part of the sprawling base several miles away. A group of us hitch-hiked to the movie site, saw the movie and were hoofing it back on a lonely dark road to our camp. Suddenly shots rang out, followed by at least five minutes of rapid automatic fire….and we were caught right in the middle of it! I started running down the middle of the road trying to leave the scene, when someone tackled me just as a few rounds went over our heads. I thought he was Japanese, so was fighting him with all I had until he cold-cocked me, put his hand over my mouth and at the same time put a strangle hold around my neck until I relaxed. We landed in a ditch on the side of the road under some foliage eating coral dust when I finally realized he was one of the men from the infantry camp. We stayed there a good ten minutes, petrified, barely breathing until a convoy of 6X6’s and jeeps with machine guns came by and stopped just up the road from us. They unloaded a few rounds and the 6X6’s started to play their lights on the hill above us.

The next morning the whole island was talking about the attack. A sentry had discovered somebody running from the huge supply depot, leaving a trail of cast-off food stuffs; it was thought to be a group of Japanese too proud to surrender.

A patrol, made up of GI’s from our infantry camp, were told to form up and hop in the trucks for a work detail. I was coaxed to go along. We stopped at the supply depot, loaded boxes of rations of every sort, medical supplies, and bags of rice. We hopped onto the trucks again then took off in a convoy of weapon carriers and well armed jeeps for the back country. We left the road and headed for a gully where we off-loaded the supplies and started carrying them on our backs. We must have traveled into the brush a mile or so until we came on a wide opening of foliage and trees, where we deposited the supplies. We then retreated back the way we came leaving the supplies for the starving Japs.

Nothing lasts forever, so they say, and one day the transportation officer handed me a travel order which stated the destination as a “Ship FS1A…………1st available land, air or sea transportation, Priority 1.” He wasn’t sure but thought the ship might be at Morotai, and a flight was leaving within the hour.

While going through the ATC boarding procedures I noticed I was being treated different from normal, as I had to pay cash for meals and other expenses. On the travel order I was classified as a deck officer. I soon found out that officers pay for everything as they go, then get reimbursed later.

I arrived at Morotai, but no ship. Seven stops and two days later I had no money left to eat on. The odd thing was the response of the ATC flight personnel. They had never seen travel orders with a ship as the only destination, without a base or port name. They seemed to have fun trying to send me off on wild-goose chases. They even considered trying to send me around the world. They finally radioed Biak for advice and the ship was found tied up to a dock in northern Mindinao, with Zamboanga the closest ATC air base. I stayed aboard a sistership FS13A for a few days until my boat arrived. Less than six months later, FS13A blew up at the dock at Manila, losing several of her crew. Avgas and smoking do not mix.

NAUTILUS SHELL

SHOWING CHAMBERS