A MIKI-MIKI TUG

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

I lost my job as a machinist helper at Los Angeles Shipbuilding and Dry-docking (Todd Ship) for fighting. I also lost the right to live at Wilmington Hall, a housing development for defense workers.

I.U.M.S.W.A. Local 9 sent me over to Long Beach for a job interview. I boarded the big red Pacific Electric street car in San Pedro and struck up a conversation with a gentleman seated next to me. He introduced himself as a Captain of a new ocean going tug. After listening to my woes he suggested that if things didn’t pan out I should get in touch with him, and he gave me his card with directions to his ship sketched on the back.

After filling out applications and interviewing for several jobs it was obvious no one wanted to hire a trouble maker. I was out of money, no job and no place to stay. I thought I’d look the Captain up, so boarded the ferry to Terminal Island and followed the directions on the back of his card. I came to the front gate of Hodgen-Greene-Haldeman Boat Works and showed the Captain’s card to the guard. He pointed out a path through the new hulls in various stages of completion, past the shops, then to the docks.

There she was laying along side the wharf; a dark green vessel with workmen climbing all over her decks and house. On the dock were piles of rope and boxes stacked many high. I approached a group of men near the gangway and asked if they knew where I could find the Captain.

One fellow in dirty coveralls said “Hi Kid, what took you so long?”

From that moment….my life changed completely, a transition from a 17 year old kid lacking in values or obligations and no doubt heading for trouble, to a life of adventure and excitement.

The Captain took me to the yard office and had me hired as a watchman since the Army had yet to take possession of the ship. He also showed me to a berth in the fo’c’sle and outlined my duties, which included making rounds checking and securing mooring lines as the tides changed, taking soundings of the water depth in the bilge, and standing fire watch. The ship was launched in late October; I came aboard shortly after and before any crew was assigned.

“She”, a U.S. Army L.T., was a 127 foot ocean-going wooden tug of the “Miki-Miki” class, twin screws, powered by two 700 h.p. Fairbanks Morse Diesels. One of the very finest tugs built for the war effort.

The name MIKI-MIKI sounds like the sing-song language of the Islands. Someone said that it meant something on the order of “hurry-up” or “be on time” in Hawaiian. The crew figured that if MIKI-MIKI referred to a tug with twin screws then one MIKI meant a single screw tug.

Hard physical labor was never one of my strong suits, and outfitting a new ship was as hard a chore as anything I had ever done. We manually carried all the stores, supplies and equipment aboard and then stowed them in their proper places; and did this while the shipyard workers were all over the place putting on their finishing touches.

After a couple of weeks the Captain took me to the Los Angeles Port of Embarkation to sign me up in the Army Transport Service as a crewman. I then went to the Post Office in San Pedro to pass a physical, get my seaman’s Passport and Endorsement Certificates. How proud I was! I couldn’t wait to get my seaman’s fold up wallet with the chain attached, an obvious symbol worn by all merchant seamen on the waterfront.

The crew started reporting aboard and I signed on as a messman. We had 14 men in the crew. Sea trials went well and we were waiting for our first assignment. The weather turned bad; drizzle, wind, and cold as hell. Nothing is so boring as just sitting and waiting. Finally our first job: down to San Diego.

Every one was excited to finally be on our way. We took off before dawn, which seems to be a pattern for ships, to always leave early in the morning.

Making coffee, setting the mess table, serving meals, cleaning the mess area, doing dishes, pots and pans, and cleaning officers cabins; it kept me busy but I really liked it. I felt I was finally contributing to the war effort.

We were underway for an hour or so when I noticed it was getting harder to keep my balance. Things were falling all around me and the mess deck was really a mess. The crewmen were coming in with wet foul-weather gear dripping all over and were saying how bad the weather was. The ladder to the wheel house came down into the center of the mess area, and down came the first casualty. Seasick as anybody could be, he got to the bottom of the ladder and then gave it up in front of everybody. Have you ever seen someone yawn? How contagious that can be? Well, sea-sickness has the same effect. Over half of the crew got sick at that very moment. I was almost finished cleaning the mess when the Captain yelled down for relief on the wheel. I went to the wheel house and the same scene met me there. I was asked to clean it up. I found some pine oil and ammonia, it was all I could do to keep from joining the rest of the men. When I finished cleaning the bridge the Captain asked me to take the wheel. I stayed on it for close to four hours and had one hell of a good time trying to surf along in the following sea. Since it was too rough to cook a full meal and no telling how many would show up eat it anyway, the captain told the cook to make sandwiches…. and that I was the new deck hand as of that moment.

I had been (at one point in my young life) a deckhand on a commercial jig boat out of Santa Monica. My chore was to grind mackerel and tin foil into 55 gallon drums for chumming. When we were out fishing I’d flip it on the water’s surface to attract the tuna, and sometimes they’d school so tight you could walk on them. The crew of the Marianna III (which later went aground and broke up under the Santa Monica pier during a storm) jokingly called me the “Master-baiter”. Thus, my “sea legs” were well developed long before my trip on this tug.

The Captain wouldn’t let the seasick deckhands back in the wheelhouse. They stayed out on the “Widows Walk”, a built-up, stanchioned walkway around the outside of the wheelhouse. They were trying to convince him that they were over being seasick, soon the seas subsided and we were approaching Point Loma. The Captain finally relented and called someone in to take over the wheel and then he told me to go below and turn in.

I heard the engine room telegraph bells but took no notice of them. I was almost asleep but I could feel the vibrations of the engines maneuvering. I thought we were docking, and they sure didn’t need me up on deck, so I just rolled over and fell into a deep sleep.

To be awakened by suspension in freefall then slammed to the head of your bunk is as subtle as being hit by a freight train. All hell broke loose. I thought we collided with another ship or hit a dock going full speed. The violent motions brought me to my senses and I glanced around and saw that no one else was in the fo’c’sle. Were we sinking? Just then we dove into another wave. I tried to go up through booby hatch but a wall of water tried to come in as I opened doors to the deck. My only chance was to go through the engine-room passage way and then on up to the deck. My primary concern was if I had time to get out before the ship sank. Not more than one minute passed from the time I was awakened to getting to the bridge. A deckhand was at the wheel and no one else was around.

“Where the hell is everybody” I screamed.

“Back aft at the towing winch!” the helmsman replied.

Just then a heavy wall of sea crashed into the wheel-house breaking out two windows on the port side. Glass scattered every where. I remember stepping on one piece and sliding across the bridge pulling charts, books and whatever else I could grab for, trying to keep from falling on the glass shards on the deck. I told the helmsman I’d go aft and tell the skipper of the damage.

About five men were working with pry-bars around the towing winch and another cluster of men were trying to get a chain stopper on the two and a quarter inch towing wire. I spotted the Captain and told him of the trouble in the wheelhouse. He said he didn’t have time to go forward and ordered me to grab a hammer, nails, and boards off some crates from the engine stores and board up the windows.

I stopped by the winch and found out that the automatic tensional and retrieval mechanism failed, causing an over-ride of the wire through the level-wind. Only then did I realize that a huge ship I caught sight of was not following us, but that we were towing it. I found out later that a couple of tugs had been standing by with her just inside the harbor awaiting us. It was just a simple matter to hook her up and go. “Her” being one of the largest concrete tanker ships ever built at the Kaiser Yard at National City, 245 feet, with a donkey boiler to work her cargo pumps.

I was able to rip enough crate tops off and make my way to the wheelhouse. The helmsman said a couple of waves had already crashed through, and would I hurry the *@!#!! up. The Captain had told him to hold a course just off the direction of the oncoming seas, but favoring to the starboard. Our speed was just enough to maintain headway and keep from being overrun by the tow; a dangerous situation as many tow-boatmen know. The Mate had control from the after maneuvering station and could telegraph the bells to the engine room. But he couldn’t steer, he could only send a rudder angle by a repeater to the helmsman.

My first trip on the widow’s walk confirmed why it was so named. Luckily I left the boards in the bridge to be handed out as I needed them. One eye on the oncoming sea, one hand to hang on with, and one hand to place the board, place the nail, and drive it with the hammer, all this with a bulky life jacket, sopping wet and freezing cold. There were a few spooky moments but all went well. The squall passed and everything settled down.

The Engineer was able to ship the level-wind fairlead to one side and disable its driving gear. He was also able to get the winch to pay out and retrieve manually, requiring a man to stand by on the ready.

There is some law that says “If something can go wrong, it will”. And it did.

Every one congregated in the mess rehashing the night’s efforts. So many things had gone wrong. I served coffee and sandwiches, I was still doing messman chores but I was now in the log as a deckhand.

The Captain was generous in his praise to all, as everyone contributed heroic efforts to overcome the many problems that developed that night. He even admitted he had been ready to write the crew off just a few hours earlier. He reassigned sea watches to provide a man to stand a towing-winch watch, I was on the 12-4; it was then 2100. I thought I’d go below to get on some dry clothes and lay down for a little shut-eye before my watch. With the rhythmic drone of the engines as we gently rose and fell with each swell, I was soon sound asleep.

Bells started ringing. We were being tossed about just as we had been before, but this time it caught us all in our bunks. Good thing I had hit the sack with my clothes on. I was up the ladder and out on deck just as the tanker barge went by on our port side. We were trying to retrieve our tow-wire without wrapping it up in our props. After reeling in the wire we found the bridle had parted near the flounder plate.

The skipper had a trumpet to his mouth shouting orders to the men at the rail. “We’ll make a pass….As soon as you think you can make it, “JUMP!!”

The plan was to get two men on the tanker-barge to take lines and secure them to the bits to control the barge’s heading until help could arrive or we could make into L.A. Harbor.

“Ready now…OK…JUMP!” came the order from the bridge. The Bo’s’n jumped, but the second man didn’t….he must have chickened out.

We could see that the Bo’s’n had fallen and hurt himself. He lay on the deck grabbing his ankle and when the Captain asked how bad he was hurt, the Bo’s’n pointed to his ankle then held up both fists and jerked them as if he was breaking a twig, leaving little doubt as to what happened. He got up and tried to hobble around but he shook his head and sat down.

We were making another pass at the barge, the mate told us to stand by and the Captain was again yelling through his trumpet. To this day I would swear the Captain was looking straight into my eyes. “When we get along side, jump!” So help me, I thought he was yelling at me. I thought I was being called on to do a dangerous feat. I had to rescue that poor soul who had broken his ankle. My moment to shine and I wasn’t going to fail. I was psyching myself up for the big leap and I didn’t pay attention to any thing else around me. I was standing on top of the bulwarks holding tight to the house overhang. The tug was rocking, the wind was increasing and the barge was getting closer. I could hear the telegraph bells responding back and forth. The engines would stop then start again. The tug would vibrate. We were closing fast…. and then I heard the order.

“JUMP!!” yelled the captain.

I timed it perfectly, I almost flew across…. but I did notice something….or someone….going the other way.

“What the hell are you doing over there? You stupid @!*!!, who told you to go!” It wasn’t a question it was more of a threat.

On the deck of the Miki-Miki tug was the whole crew, looking at me shaking their heads, even the injured Bo’s’n. Everyone, with the exception of the Captain, was laughing. I felt so stupid. Somehow I had missed out on the plan of action. After much maneuvering and cussing the captain worked the tug close enough to the tanker so I could jump back aboard.

Another tug soon came on the scene and we were blinking back and forth with the signal lamps. The seas settled down to a gentle swell and it was about time for me to go on watch.

I wasn’t looking forward to facing the Captain and luckily for me he was more concerned with assisting the other tug to get lines aboard, and heading for L.A. Harbor than he was in chewing out his new deckhand.

The rest of the trip was uneventful. We went into the shipyard for three days of repairs, then picked up the same tanker ship and headed for San Francisco without any further crisis. We also signed on a new messman.

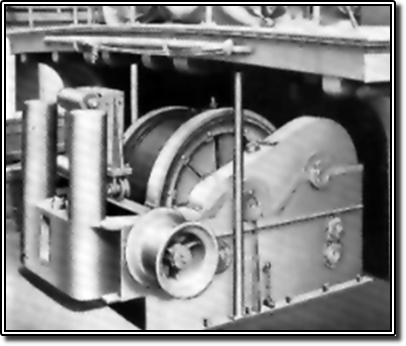

Photo at right shows a

MIKI-MIKI TUG’S

towing winch.