ABOUT

The following events are my personal recollections about the little known quasi-military organization that I served with, its ships, and the men that sailed them.

During World War II the U.S. Army Transportation Service, which later became the Army Transportation Corps (Water Division), was the largest sea-going force on earth; larger even than the U.S. Navy at its peak. It included more bottoms (hulls)…greater tonnage, and operated around the globe in more areas than any other maritime entity.

Many crews of the ATS vessels were of mixed nationalities; in instances that I was very familiar with, several Swedish officers said that to be allowed to sail aboard American vessels they had to change their identities to Norwegian because Sweden was a neutral nation (mentioned in the stories (ATLANTIC CONVOY and MULBERRY). There were Aussies and New Zealanders (OCEAN LIGHTER and ZAMBOANGA MONKEY CAPER), Chinese (OCEAN LIGHTER), and Filipinos (FITCH the BITCH). I’ve heard of many other nationalities serving on the American flagged “LITTLE SHIPS”.

What is amazing….as I understand the law which passed in 1987 giving veteran’s status to merchant seamen…any foreign seamen who sailed under our flag were granted, by our government, the same military veteran recognition and privileges as native or naturalized Americans, even if their own country didn’t recognize their war-time service. I can only surmise that it was because the foreign seamen were compelled to sign Civil Service documents pledging their allegiance to the U.S. during their tours of service.

During the war newspapers were filled with tales of merchant seamen earning astronomical wages and being paid off with huge bonuses. I certainly did not….and I never knew or met anyone who did. I don’t know who to credit with those lies but lies they were.

I first signed on a ship as a mess-man in 1943 on a wooden Miki-Miki Large Tug. As I upgraded to more responsible positions and sailed into combat zones I earned better pay. But consider this; a deck sea watch on a mid-size freighter would consist of a Mate, one or maybe two Able Seamen, and an Ordinary. Engine department watches consisted of an Engineer, Oiler, Fireman/Watertender, and maybe a Wiper. Compare that to the watch assignments of the Navy. I am not talking about combat ships but I am comparing two identical service ships doing essentially the same duties. The Navy will have two to three times the men per watch. In our case, with fewer men on watch and more chores to tend to, the burden of responsibility drastically increases. That, in my opinion, would justify our earnings, plus, we received no fringe benefits or allowances…WHATSOEVER. If you were in the hospital or on the beach, your pay stopped.

Within the Army Transportation Service there was a separate entity called the Water Department (small boat division), affectionately dubbed “THE LITTLE SHIPS” by those of us that sailed on any of the myriad of vessels that plied all the waters of the world.

To list them all here would duplicate the wonderful job that David H. Grover did in his pictorial review U.S. ARMY SHIPS and WATERCRAFT of WORLD WAR II published through Naval Institute Press Annapolis, Maryland. There were many vessels constructed in foreign countries for very specific and unique duties. Only the men who sailed on those vessels would recall their designations such as: OL A’s, OL B’s, OL W’s, FS’s, FP’s, FS-A’s, FS-B’s, ST’s, TP’s, T-boats, MT’s, etc. Many of these were older vessels or were purchased overseas during the war to provide emergency service. An American flag was planted aboard and crews were assigned through military manpower pools in all the major ports of Great Britain, Australia, New Guinea, and the Philippines. At times the deck crews would consist of Civilian Officers and regular U.S. Army GI deck-hands who were made up from several Army Transportation Corps, “HARBOR CRAFT” or the Army’s “SHIP AND GUN CREW.” This last group was assigned to man the guns; a counter-part to the Navy’s “Armed Guard” who crewed on the larger civilian merchant ships.

The engine crews would at times be a greater mix. I remember on one 112′ Australian built Fairmile “B” (FS A) that no experienced gasoline Engineers were immediately available in the area and a U.S. Army Air Corps Sergeant was temporarily assigned as the Chief Engineer. I became his assistant only because it took four hands and four feet to handle the throttles, clutches and Johnson bars (shifting levers) for the two-high-octane gasoline, high-speed Sterling aircraft engines.

While serving in certain forward combat areas we were required by either the area’s military commander or our vessel’s skipper to wear undress army uniforms. In several instances while ashore I was challenged for inappropriate attire, they found it hard to believe that I was a civilian and not G.I.

Our mail and payroll records were always late or lost when sent to an old APO address to New Guinea and wouldn’t catch up to us in the Philippines for months, forcing us to draw only small advances from our ship’s emergency fund.

I’ll wager many men who sailed with the War Shipping Administration are shaking their heads as they read this wondering how so many of us could get caught up in such an off-beat organization but I am damned proud to have been a part of it. I had only one good eye and as the war progressed I was forced to stay behind and watch all my high school buddies join up. I felt I was as good a man as any of them, and it hurt to be rejected by all the services.

I knew that while working in the shipyards I was performing a patriotic duty, as the construction of ships was vital to the war effort. What we did not realize was just how important our shipyard work was because our government refused to release the tally on the slaughter of merchant ships and men by the U-Boats on the East Coast and North Atlantic. A damned good exposé of the ineptitude at the time by those in charge is divulged in Michael Gannon’s “OPERATION DRUMBEAT,” published by Harper & Row.

There were many men in similar circumstances to my own. They were either too young, too old, or had physical deficiencies. It was said that if a man had at least one good eye, one good leg and one good arm, and not necessarily in that order, the ATS would hire him.

Just why I stayed with the “LITTLE SHIPS” is not hard to explain but there were times when I did try my hand on the big ships (PIERHEAD JUMP or FITCH the BITCH) plus there were others I’d rather forget. I think it was a case of having had responsibility for the first time in my life and having other people willing to rely on my performance and not being just another small cog on a huge gear. Besides, where else could a man sail in every capacity aboard every kind of vessel and on every ocean of the world…without the need of a license?

It was customary to sign up for a one year contract. You agreed to crew in any capacity, on any vessel. It was not uncommon to be assigned to several ships for very short periods of time. Sometimes it was to replace men heading home, taking a promotion to another ship, or going to the hospital; it didn’t matter and technically we couldn’t refuse to transfer from ship to ship. I personally found it exciting to cover new ground, especially if it meant a promotion or going to a new ship or new area of duty.

The “LITTLE SHIPS” were scattered around the world. They were in Alaska, Scotland, England, through-out the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, China Seas, and all over the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Any activity involving the Army or the Army Air Force meant the ATS was near-by. Supply ships, repair ships, air/sea rescue, tugs, mine layers, target towing, self-propelled cranes, troop transports, hospital ships, communication vessels, dredges and salvage ships…we had them all.

General MacArthur considered the ATS his own private Navy.

A few shining moments of World War II that were kept secret long after that war was over, occurred during the Normandy invasion, June 6th 1944. Two important operations that contributed to the success of that landing were code named “CORNCOB” and “MULBERRY”, both involving civilian merchant seamen. Civilian Crews of the first operation “CORNCOB”, scuttled their still functioning ships in rows off the invasion beaches to provide shelter for the landing crafts; all the while drawing fire from the German shore batteries. Among the scuttling “Corncobs” were six ST’s (Small Tugs) manned by ATS civilian seamen who aligned the Corncobs for their scuttling.

“MULBERRY” was a massive secret operation in which large concrete caissons were constructed in Scotland and England and towed to Channel ports to await their delivery for the construction of the “Eighth Wonder of the World”: two artificial harbors of enormous proportions. They were designed to provide shelter for the landings until a major seaport could be secured. Tugs of every size and description, flying many flags, civilian merchant seamen and navy manned, and of course the “LITTLE SHIPS” were well represented.

When we arrived home and told of our experiences no one wanted to believe that civilians were involved in the invasion. Our government kept “OPERATION MULBERRY” a secret for many years but merchant seamen and the men of the ATS were to eventually receive recognition for that service, albeit some 45 years later.

A supporter in the cause for Army Transport Service recognition is the noted historical writer, Charles Dana Gibson. Mr. Gibson has researched the “Army’s Navy” from day one of its inception during the Revolutionary War and has published several books covering several periods of its history. He also represented the ATS and was signatory to the negotiations granting us veteran status.

While researching material for his documentary of the ATS in World War II he was informed that the ship logs of the “small boat division” were destroyed, intentionally or otherwise, no reason was ever offered. So it’s no wonder that no one has ever heard of us. His book, “The Ordeal of Convoy NY 119”, epitomizes in great detail and pulls no punches regarding both the high and low character of the “LITTLE SHIPS” and of its crews. I oft-times have envisioned myself being in the midst of all that turmoil.

I admit to having led a less than a stellar seagoing career. Maybe the liberties ashore with a few bucks burning a hole in my pocket, mixed with a bit of youthful exuberance, led me in directions that I can only remember now as exciting experiences which, over the years, I have jotted down for someone to read and enjoy long after I’m gone.

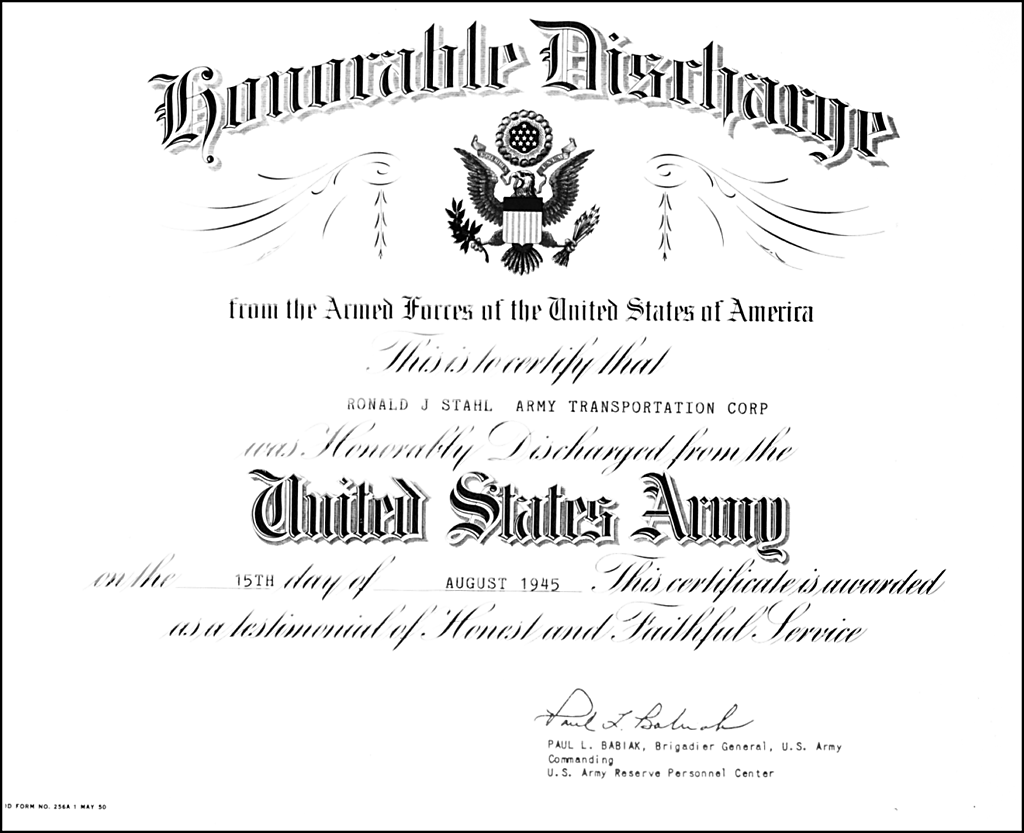

Ron Stahl, Army Transportation Corps