H.M.S. PRIMROSE

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

H.M.S. PRIMROSE

Destination Murmansk

This tale is of an American merchant seaman whose ship was sunk by a Nazi U-Boat in a previous convoy when approaching the western waters off Iceland. After having been adrift on a life raft for two days he was rescued by the long-range armed trawler, HMS Primrose. This tale could have been told by any number of survivors of the North Atlantic convoys who were rescued by one ship only to suffer more terror when their rescuing vessel also came under heavy attack.

*****

Two days adrift on a raft on the frigid waters of the North Atlantic seemed like an eternity, especially after being warned not to succumb to “that everlasting frozen sleep.” After all hope of rescue appeared to be waning as each day went by, our survivor entered that realm of hallucinations, dreaming of snuggling down in his watch-coat and foul-weather gear, damp as they were, but staying warm with what little heat his body had to offer from the chilling wind. That was the last he remembered…until…he first heard voices and tried to roll over. Something was restricting his movements, panic overtook him and he started fighting and thrashing about, struggling against the many hands that seemed to be holding him in check.

“Easy Mate you’re in good hands now,” a comforting voice spoke out. “Take it easy; here, have a ‘cuppa’, it’ll do you wonders.”

His eyes opened and met the gaze of several faces staring at him. He tried to pucker his lips to the cup but they were cracked and swollen. He bolted back from the cup causing some of the warm tea to splash on his chest and uttered, “God that feels good,” then tried to show a smile but that opened another painful crack in his lip.

“You’re a very lucky man,” said a voice with a heavy Scot brogue, “We almost passed you by thinking you were a goner, so no reason to risk our ship by stopping to pick up another corpse. We unloaded a few rounds to sink your raft so no U-boat can lurk beneath it to surprise another unsuspecting rescue vessel. We’ve sent for the skipper… Here, let me help you sit up. Are you hurting anywhere laddie?”

“I seem to be in one piece,” the survivor uttered, squeezing one arm and then the other. “What ship is this? How long have I been out?”

A youthful ruddy-complexioned officer with a neatly trimmed beard and mustache, wearing a naval officer’s blue jacket with two thin rows of interwoven gold lace on its sleeves, elbowed his way through the helpful throng in the very close quarters. “Welcome aboard. You appear to have come through your ordeal in fair shape. I’m Lieutenant Leland Perry, Captain of the HMS Primrose…What ship were you on? When and where did it get hit? I need the information for my log.

We went through everything you had with you. We found papers on you that indicated that you are second officer Theodore Dominy, is that so?”

“I go by Ned Dominy, second mate of an old Standard Fruit ‘reefer’, S.S. Lake Passaic out of Charleston, bound for the UK by way of Halifax. We had an overheated Kingsbury thrust and were trying to nurse it on into Reykjavik. We left our convoy during the night. My last D.R. was about 80 miles Southwest of Reykjavik. I can’t remember if we got hit on the night of the 2Oth or the 21st. I was just going out on the starboard wing when the whole ship seemed to explode. The next thing I knew I was pulling myself aboard a raft…the ship went down almost immediately…I doubt if many of our crew got off in time…I kept yelling and blowing my whistle…but….”

“At the moment we are quite busy trying to organize our convoy. I’ll send my Yeoman down to get any further information you may have overlooked. As soon as you’re able…get up and enjoy the freedom of the ship. She’s tiny but very able.” With that and a nod of his head, the youthful skipper left the compartment.

Other than the slightly numb and chapped hands and lips, plus an ever-desire for a warm drink, Ned could find no other major body hurts or pains. Thank God for good foul-weather gear. He slid out of the tiny pipe rack with only a blanket around his body and started stretching and doing knee bends. Though painful in knee and elbow joints he felt to be in one piece. One of the crewmen tossed him a pair of shorts, socks and wool trousers; another gave him a turtleneck sweater. When Ned went into the head and saw himself in the mirror he couldn’t believe the ugly image he was staring at. Open sores gaped on his forehead and cheeks, his lips looked like inflated sausages and he had the start of a scraggly beard from days without shaving. Gingerly, avoiding the sores on his cheeks with great care, he proceeded to make himself as presentable as he could with the proffered razor, toothbrush, comb and a half-bucket of fresh water to bathe in.

Ned was tall, six feet plus, of slight build and had a head of curly black hair that contrasted with his fair skinned frame.

A crewman escorted Ned to the Petty Officers mess and on the recommendation of the ship’s cook that he should begin eating lightly at first so as not to get constipated, Ned devoured a bowl of mush with condensed milk and a hot biscuit with marmalade; the tea was the most desirable of the lot.

Several men were playing Cribbage at the other end of the long table with their incessant rhyming “fifteen-two fifteen-four and the rest don’t score” as they counted the holes before planting the peg.

A player looked up and called out to Ned, “Hey Yank…’ow’s it feel to be aboard our little cork in this big ocean after coming off that giant cargo ship you were on?”

“If you mean my ship, she was only a few feet longer than this ship of yours at 250 feet and I’ll bet a hell of a lot less stable,” Ned replied, not knowing if the seaman was serious or just offering conversation. Of course, the remark could have been sarcastic as a lot of Brits still resented that the Americans were letting England take the brunt of the war. The bombing of Pearl Harbor several months ago still didn’t erase that resentment. A crewman wearing a shirt, black tie, and jacket with red chevrons under crossed quills and a crown on its sleeve (an unfamiliar rank to Ned) sat down next to him and opened a round tin of balm and offered to spread some on the sores on his face. “This should relieve the soreness and help heal the chapped areas, Yank. What part of the states are you from? I’m Jimmy Richards….Leading Yeoman ‘signals’…everyone calls me ‘Flags’.”

“Glad to meet you Flags,” Ned said extending his hand. “Your skipper said you’d be down to get any information I may have forgotten. My home is in Port Townsend, Washington but I ship out of New York. We were heading for Liverpool with a load of frozen meat and chilled fruit and vegetables when we got hit. When do you think we’ll make port?”

“Sorry to tell you the bad news,” Flags offered as he carefully spread the balm on Ned’s face, “but we’re just starting on a new assignment and have yet to receive our final sailing instructions. So it looks like you’ll be with us for awhile.”

Suddenly the ship heeled over to one side and stayed there for what seemed a long minute. Ned braced himself as best as he could as all the cups and condiment articles that were not confined slid from the tables to the deck. The fore part of the ship rose and for the longest time seemed suspended in mid-air then dropped, slamming down hard as if going aground; a typical experience when a small vessel comes about and heads into heavy oncoming seas.

“Get used to it Yank, we ‘aven’t ‘it no weather yet. Wait ‘till you ‘ave to lash yourself in your bloody sack,” mouthed the Cockney-accented grump playing Cribbage.

Ned thought for a moment for a proper reply and was about to unload when Flags interceded in his behalf, “Come off of it Charlie, don’t take your hate of the Yanks out on this man. Ned nearly gave his life trying to get supplies to us. Just because your sister got knockered by a Yank doesn’t mean they’re all bastards.” That outburst answered several questions for Ned and relaxed the tension in the mess.

Flags, now ignoring the cribbage player, filled Ned in on a bit of the history of the little Primrose. “She was launched in early 1937 to be used as a service and supply vessel for a fleet of long-range fishing trawlers. She proved to be a very able escort but the cost of operating her in that manner was most prohibitive when the selling price of landed cod was so depressed. The Primrose is 162 feet in length over all; she has two oil-fired water tube boilers and a powerful triple expansion engine that permits her to cruise for extended stays at sea. Her heavy displacement hull makes her quite sea kindly even when cruising at near twelve knots.

“Early 1939 the Admiralty had put her in a yard for a refit. They beefed up and enclosed her forward well deck, extending the new forecastle deck aft of the stack thus allowing for more usable crew accommodations then added a three inch dual-purpose gun just forward of the wheelhouse and quad-mounted two-pounder Pompom atop the after house, several 20mm Oerlikons, and a rack for depth charges, a towing winch, and accommodations for a crew of fifty-plus. Seamen and stokers are berthed forward, slinging their hammocks above their mess tables. She became the design leader for her five little sisters, H.M.S.’ Compass Rose, Cottage Rose, Winter Rose, Village Rose, and Wind Rose. Many of Primrose’s innovations were incorporated in her subsequent larger sisters, ‘The Flower Class’ Corvettes, which became the venerable workhorses of convoy duty worldwide.

“One bit of irony,” Flags continued, “is the fact that nearly a year ago, in June of 1941, several of Primrose’s sisters were sent to provide escort duty not only to British flagged vessels that were bringing much needed supplies to the UK and were sailing from British territories in the Americas, such as the Bahamas, Jamaica, British Guinea and several other smaller possessions, but to all allied flagged vessels entering and leaving these ports. Because of an agreement between nations, America was supposed to supply safe passage to these vessels as far as Iceland. However, a top Admiral of the US Navy had said he didn’t have enough patrol craft to guard his own coast or his own merchant ships….let alone enough escort vessels to protect any foreign-flag ships that were entering and leaving American ports. But his rational was not surprising since he didn’t believe in the convoy system even to protect his own ships.”

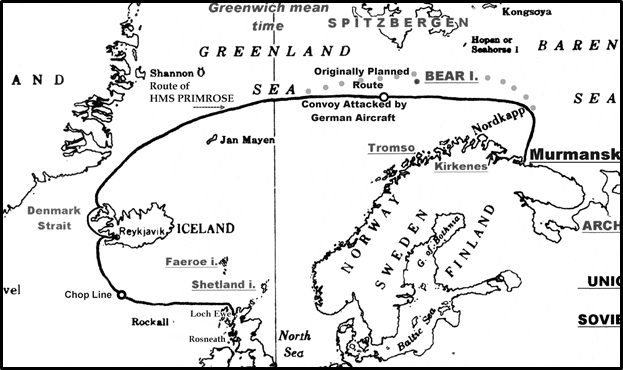

The Primrose had arrived off Iceland a few days earlier after escorting a convoy from Loch Ewe, on the west coast of Scotland. They turned over several of their charges to the Royal Canadian Naval escorts at the chopline (CHange of OPerational control) for that convoy’s final dash to the so-called safety of North American waters. Primrose along with the other escorts herded the remainder of the group to a fjord on the west side of Iceland.

The talk now amongst the crew was that they had expected to return home to the U.K., hopefully escorting another convoy east as they usually did. However, entering the fjord and topping off with bunkers, water and rations (a procedure they hadn’t done before) gave rise to a rumor that something important was brewing.

***

Ned hadn’t been aboard 24 hours and the crew already had gone through several air and surface attack drills. He soon learned the difference between that of a merchant ship and a Navy ship’s way of life. Not only were the drills unsettling to him but also to the crew, which harped incessantly when coming into the mess area after each exercise.

The loudest complainer, of course, was always Charlie, the loud-mouthed Cribbage player. He continued to gripe about everything to all who would listen or sit near him. When he looked up and saw Ned he challenged him in his heavy Cockney accent, “I’ll bet ya don’t ‘ave drills like these buggers on that fancy civilian merchant ship of yours!”

Ned allowed that utterance to pass without comment. After all he was a guest aboard, and that fact soon became a problem for him. When the drills started he was told to keep out of the way. Everyone was racing around lashing up the P. O. berths to provide more room in the passageways and passing up ammunition through a hatch from a magazine deep in the bowels of the ship. He offered his services to the mess crew to assist turning the P.O. mess area into an emergency medical facility. The process was precise and interesting; unopened stretchers were placed on the mess tables, a large locker was swung open exposing a massive variety of bandages, splints and surgical instruments, another locker held medications, and battery operated battle lamps were hung from the overhead. When the all clear was sounded the preparations had to be reversed and the area returned to the crew’s sanctuary.

Ned found the rapport between the officers and the crew was at times testy and wondered if it was because the British Navy considered Officers a privileged class. Ned found it so much more noticeable aboard this ship and very unlike any relationship between licensed and documented crewmen aboard American merchant ships. But then it could be that the skipper was putting the crew through very hard training for an assignment only he was privy to.

After supper Flags appeared in the P.O. mess, pulled Ned aside and whispered that his presence was requested in the officers’ wardroom.

Ned made himself as presentable as he could before going aft into officer’s country. On entering the wardroom, a white-jacketed steward asked what his preferences were and Ned said, “Tea would be fine.”

Two ‘off watch’ ship officers stood as the skipper made introductions; then returned to their seats around an oblong table designed for six people.

“Sorry to have taken so long for us to meet with you. We’ve been busier than usual as you could probably tell…not easy trying to organize a convoy with a bloody bunch of independent-minded ship’s Masters…oops…I forgot you’re one of them…forgive me…please take a seat.” Smiling, the skipper pointed to a vacant seat at the table, “Our chief cook said you volunteered to help out in the mess. I must say, that was most gracious of you.”

“I felt like I was in the way and couldn’t find a corner to hide in; mainly did it for self defense. It was quite an education.” Ned took his seat between the two young officers. “The scuttlebutt is that this may be an extended voyage and if I might be of any assistance I beg for the opportunity.”

“I don’t know how they do it; the lowest rate in the fo’c’sle usually knows more of what’s going on even before a Captain gets his orders.” The skipper smiled and then added with a serious tone, “Normally we prefer not get too involved or familiar with survivors that we rescue, after witnessing a survivor’s physical condition and sharing their experiences, it becomes an emotional burden. We really want to help, but it does tend to distract us from our duties.”

Ned became uncomfortable with the Captain’s remark and thought to himself, “Why in hell did they invite me up here?” He was at a loss as how to respond and squirmed in his seat, showing his discomfort.

The skipper saw the puzzled look on Ned’s face and hurriedly said, “Please Mister Dominy, I didn’t mean to imply that status to our present circumstance. We’ve just received a reply from our escort commander regarding your rescue. They indicated that a transfer to another ship at this time is out of the question; first, because of the weather and second, if we were to slow down to launch our motor whaler or ask the receiving ship to do likewise, that exchange might provide a U-boat with just enough opportunity to put a torpedo into either of us. As you’re going to be with us for a while, the ship’s officers and I were wondering if you might consider joining us as an observer. It would be a shame to waste your bridge experience sitting below in the crew mess.” He then added, “Of course it all depends if you feel healthy enough.”

“I accept…I would be honored sir,” Ned hastily replied.

“Good, I have arranged for you to share a cabin with Sub-Lieutenant Barstow; he’ll help familiarize you with our procedures.” The skipper turned to Barstow, “See that Mister Dominy is made aware of our ward-room protocols and the different attack stations and duties.” He then added a flippant remark that could only be interpreted as a shipboard jibe at the Sub-Lieutenant. “Now you’ll be able to share some of your Academy training with someone other than us.”

Everyone guffawed and someone made a mock toast, “To poor Mister Dominy!”

Flags entered the wardroom and handed the skipper a typed sheet of paper with several rows and columns of assorted letters, then left. After scanning the message the skipper mulled it over for a few moments, then rose and announced to all, “It’s time for us to start earning our keep!” Then, turning to his Number One, Lt. Bridges, he said in a serious tone as he left the cabin, “I’ll meet you in ciphers in two minutes.”

Ned followed Sub-Lieutenant Barstow through a passageway and entered a small cabin that measured maybe 5 feet by 8 feet at the most. Two bunks were stacked one on top of the other, two lockers at the foot of the bunks, and a small desk and chair sat at the head of the bunks. In the space at the end of the bunks and on the bulkhead hung an odd looking washbasin like those found on some old passenger trains. The basin had to be lifted out of the bracket on the wall and slid onto a hanger clip; a rubber hose served as a drain to God only knows where. Lt. Barstow remarked with a smile, “That is a wash basin….not a urinal.” Then he added, “I’ve been using the bottom bunk but if you’re still sore, I’ll swap.”

They heard a knock on the door and someone called out, “Mr. Dominy, the Chief Engineer wanted me to bring up your duds. They’re all clean. We rinsed out the salt in warm freshwater from the hot-well and hung them to dry in the fire room.”

“Can’t get any better than this,” Ned said with a smile to the Stoker. “A deluxe suite with running water, valet service and the top bunk, please relay my compliments to the Chief.” Time was nearing twenty hundred hours (8 pm civilian time) and it was still daylight out. Barstow suggested Ned put on the warm clothes and heavy parka that was delivered because it was just about time for the evening surface attack drill. As he struggled into his clothes he found they had shrunk considerably and was on the last button when the bells began ringing. The ship suddenly came alive.

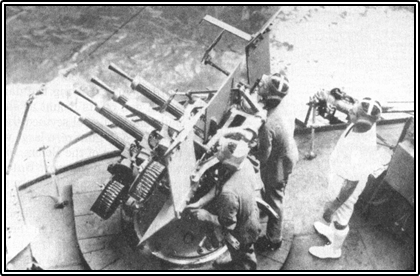

Photo at right is of a

Quad-mounted

Two Pounder Pom-Pom

Barstow yelled, “Follow me!” and they took off towards the stern and the after pompoms. “This is our action station here commanding this gun and the after emergency helm.” Then he turned to the gun crew who were rushing to their stations, “Let’s show Mr. Dominy how fast we can put her on line.” He watched the sweep-second hand on his watch, which he started at the moment the alarms sounded. The crew removed the covers from the gun and attached the heavy spiral ammo magazines. Barstow then announced to the messenger wearing a headset with earphones and mouthpiece, “Number two gun loaded and ready. After steering station manned and secured….one minute and twenty seconds. Relay that to the bridge.”

The command came down to the messenger from the bridge saying, “Fire all loaded rounds, clean and service all weapons then stand down.” The Primroses’ position in the convoy was at the tail end and between columns. Her official assignment was to act as a rescue vessel and, if necessary, take a distressed vessel in tow. This was in addition to her myriad of other duties as close-in convoy anti-aircraft defender and anti-sub trawler; she wasn’t rigged with the ‘ASDIC’ apparatus but did have the very latest sensitive underwater hydrophones.

They were one day out and two ships had already dropped out of the convoy. One went aground on leaving the fjord and the other was seen straggling behind. Primrose dropped back to assist the straggler, but the crippled ship’s Captain said he must return to Iceland for needed repairs.

Ned was allowed on the upper bridge, directly above the wheelhouse a very small area of maybe twelve feet fore and aft, the bridge wings extended to the extreme width of the ship. A binnacle with compass and azimuth stood on a raised platform that permitted an unrestricted view all around. Two inverted bell-shaped brass voice pipes were attached, one led to the helmsman below in the wheelhouse and the other down to the engineering spaces. For protection from wind and sea spray and errant shell splinters a metal dodger of sorts stood about shoulder high along the front edge of the bridge and partially along the side, the upper twelve inches was slanted forward at twenty or thirty degrees with blue colored glass on the top edge to ease any glare from the oceans surface. Aft on the bridge were two flag lockers with halyards leading down from the yardarms. In most conditions and at action stations the Captain, Watch Officer and a signalman with headset would man this area. Below in the wheelhouse was the Coxswain at the engine room telegraph, a helmsman and another signalman who would relay messages to all sections of the ship by a handset or the array of voice pipes attached at the forward bulkhead upon receiving any order from above. At the rear of the small wheelhouse was a ladder-way leading down to the lower deck separating the Captain’s small day cabin and the Navigator’s chartroom.

Ned, off to one side of the open bridge, was searching the horizon and spotted several large naval escort ships joining up with their convoy. One of the Corvettes was bearing down and as she closed she hailed, “Primrose you will retire and provide assistance to the straggler. She is eight miles distance at 160˚ magnetic. Confirm.”

The skipper’s bullhorn bellowed, “We left her twenty minutes ago. We offered assistance…her master said his vessel could make it back to port safely.” The sleek looking Corvette turned on her heel and headed back in the direction of the other escorts.

The crew was abuzz when the course “North” became general knowledge. That could only mean one thing…the dreaded run to Murmansk. The official designation for convoys going north was P-Q, so named after Commander P. Q. Russell attached to an office in the British Admiralty. The return trip from North Russia had the reverse designation of Q-P.

Ned learned from Flags that the skipper and a few of the crew had made previous runs to Murmansk on other naval vessels. Some of those crewmen still found it hard to understand why Britain was giving away arms to such an unfriendly nation as Russia when British troops in North Africa were in much greater need. Besides, the Ruskies in the two northern ports never showed any appreciation for the arms and supplies they received or were they aware of the danger the ships and their crews had to go through to get them there. Not one word of their supply effort was told to the Russian citizens. Flags added a few of his own opinions about their system of government, “If any of the socialists or communists at home could see just how depressed and miserable those people were they would become staunch conservatives overnight.”

(An Ironic footnote; Britain had built wharfs and docks only twenty-some years before at Archangel during the 1st World War and they were only in use for a short period before the Russian revolution forced them to sue for a separate peace with the Germans. Both the Americans and Brits continued to stay on in North Russia to keep all the delivered material from falling into unfriendly hands. The allies also provided food, clothing and bare essentials to the disenfranchised people who were confused and wondering if they were to consider themselves White Russians (Czarists) or Red Russians (Communist).)

***

In the several days since Ned’s rescue the convoy had steamed close to Greenland’s outer ice shelf, which was evident to the naked eye. What appeared to be large icebergs off in the distance were in fact the solid icepack with some very high peaks. In an area about a half-mile wide was a pastel green belt with large chunks of ice; Ned recognized the belt as the icy slush he had seen along the glacial coasts in Alaska. Today the sea was as calm as a lake, the light grey overcast blended almost perfectly with the color of the sea and it was hard to distinguish where the horizon started and the sea ended. The temperature was well below freezing with not a hint of a breeze. Any smoke or steam escaping from the ships’ funnels was going straight up and drifted along with the ships, giving the appearance that the ships were hanging in suspension by a thin rope; creating a phenomenon hard to believe let alone explain. Handrails and decks were beginning to ice up. Men on watch had ice forming on their beards and eyebrows. One of the watch-standers had a long knitted watch cap pulled down over his face with a large hole cut out for his eyes. Around his mouth and nose area was a solid crust of ice formed from the condensate of his warm breath.

The Commodore fired a cannon indicating a special flag hoist ordering all ships to change course eastward by 30 degrees. Primrose’s skipper was unaware of any reason for this sudden change in course. Ned overheard him discussing this new turn of events with his Number One, Lt. Bridges, and the consensus was it could be that the convoy’s screening Sloops and K-boats had picked up soundings of U-boats far up ahead of the convoy. Or, it could be that it was nearing time to lay for the ice-free passage between Spitzbergen and Bear Island.

Lookouts were doubled and then tripled. At one point a huge dark object bore down on Primrose but she was able to maneuver out of a certain collision at the last moment. The skipper hailed the ship with his megaphone and the response from the cargo ship’s master was that he had no idea where he was.

“Change your course to seventy degrees magnetic….hold your present speed….what ship are you…what is your station?” bellowed Lieutenant Perry.

“Cape Flattery…Pedersen, Master…aught one…aught three,” was the response.

“Damn fool,” mumbled the skipper. Then turning to Ned added, “This is an example of those independent minded merchant masters I referred to when you first came aboard.”

“With all due respect sir, I know of Captain Harold Pedersen. He sails out of my part of the world and is highly regarded,” Ned said in defense of the old West coaster, then added. “Cape Flattery is a new 16 knot C-1 and usually sails unescorted. We’d all be upset if we sailed on a ship capable of out-running the U-boats but now has to be held in check to match the speed of the slowest bucket in the convoy, such as my old ‘Lake Passaic’; she was worn out and should have been broken up long ago. It took everything the crew had, from the Captain down to the Wiper in the engine-room, to keep her running.”

“Touché Mister Dominy, I’ll control my remarks in the future. Just in case it may be of any interest to you, I too sailed on civilian vessels for several years before the war while participating as a naval reservist. The RN is an entirely different way of life and discipline is the basic difference between it and the mercantile marine. I suppose the age of the ship and her condition could cause some consternation amongst the crews.” Throughout the morning and well into the evening Primrose was rounding up strays and placing them in their proper rows and columns, a chore much like that of a tenacious sheep dog nipping at the heels of its wooly chargers.

During a lull while escorting a stray back to the pack, the Primrose’s Captain renewed the conversation with Ned regarding the strict discipline required in the RN in contrast to that of the American merchant marine.

Ned responded, “A bill is being debated at this time in the US Congress to incorporate the Merchant Marine into the US Navy, on the order of your own Mercantile Navy, but opposition is coming from all sides. The Navy really doesn’t want us. The shipping companies don’t want to give up their control of ships. The Maritime Unions don’t want to lose their grip on their captive manpower and the poor seaman would have little say as to his wages, living conditions or freedom of expression. Plus, there are many seamen who couldn’t pass a physical because of age or handicaps…. even though they handle their duties very capably while at sea.” Then, as an after-thought, asked, “Captain Perry can you envision a man like Captain Pedersen of the Cape Flattery, at seventy-plus years, changing his opinions on how to command his own ship? I certainly cannot.”

***

With a light breeze over the stern dispersing the fog, at the start of daybreak, the convoy entered the Barents Sea to begin their eastward heading. The Commodore fired his cannon and signal flags were hoisted; all ships acknowledged the signal by duplicating the hoist. The flags warned of an “eminent submarine attack.”

Distant thunder could be heard far ahead of the convoy. Even the crew below decks could feel the concussions of what they feared might be depth charges. The lead screeners must have made a confirmed contact, and everyone knew it wouldn’t be long before the convoy could soon become the targets.

Many seamen fall into a common mode when they sense they are about to go into danger. They wrap their photos and important papers in waterproof packets, they suit up in clothing that they think will protect them…just in case, and many will not linger for any more time than is necessary below decks…opting to stay in the crews mess and pretend to play at cards. But what is most obvious are the hushed conversations; many just sit with their head buried in folded arms, wanting the time for themselves to think only of personal and private thoughts, and waiting for their turn to relieve those now on duty.

From the moment of that warning shot from the Commodore, Primrose took to her action stations. She came about and headed for her defensive position at the rear of the convoy and began zigzagging at a fair rate of speed to maintain hull speed for any eventuality, even the possibility of rolling off a few depth charges. She didn’t have long to wait; a tremendous explosion erupted near the head of the convoy. The smoke appeared to be coming from the area of column one. Ships were maneuvering radically to miss the partially submerged hull and men that were visible in the water. It took only a few minutes for the entire convoy to pass by the flotsam left by the torpedoed ship.

Primrose spotted a group of seamen struggling in the water around a raft. She passed them close by while still maintaining her hull speed. Lt. Perry hailed the group advising them that he would come about to rescue them. Several of the nimble escorts were scouring the area with their ASDIC’s. They appeared to be converging far off to the left of the convoy when one of the Corvettes must have made a fix; she hoisted a series of signal flags then proceeded with a depth charge run.

Convoy rules precluded merchant vessels from stopping to pick up survivors, leaving that task for the smaller close-in Rescue vessels. Word was passed to the Primroses’ crew to rig out the webbed scrambling nets and to prepare to take aboard survivors. She worked her way in close to the raft, which was overcrowded with shivering men. Several of Primroses’ crew now, wearing survival suits, jumped into the sea to help those unable to climb aboard the raft. They maneuvered the injured men so they could cling to the scrambling nets as men aboard the Primrose hauled on lines attached to the lower end, effectively rolling them up like pursing fish in a net. The whole operation took less than five minutes to save 47 men of Cape Flattery’s 64-man compliment, which had included 16 US Navy Armed Guard. Several of the men who didn’t survive were lost as a result of the extremely cold sea temperature. A man could last but a few minutes, unprotected, in those frigid North Atlantic waters. Primrose made several passes searching the area for more survivors without any success.

The skipper asked Ned to go below to see to the needs of those rescued and to temporarily act as a liaison between him and the ship’s survivors. He instructed him to get as much information as he could, so that the Primrose’s officers could keep to their action stations during this emergency.

As Ned entered the P.O.’s mess he was met with a most gruesome scene, men lying prostrate, in shock, on the deck. Others balled up, their bodies shaking uncontrollably, some thrashing about in agony. Others were sitting around dazed, puffing on cigarettes, still in their wet clothes; several who had bloody wounds were being tended to by their own shipmates and by Primrose’s Sick Berth Attendants.

The mess area was warm because of the piped in steam heat. Ned took off his watch coat and draped it around a shivering elderly gent with a bowed head and then introduced himself to the crowd, “My name is Ned Dominy, previously 2nd Mate of the Lake Passaic. Like you I am also a survivor. The Primrose’s skipper, Lieutenant Leland Perry, has asked me to see to your needs. He will come down as soon as the present emergency is over. Are there any officers among you or someone who can speak for your group?”

“Chief Mate here,” said a man holding up his hand. “That’s Captain Pederson over there,” he said, pointing to the man with Ned’s watch coat draped about him.

The trill of the Boatswain call bleated from the overhead speaker. “This is the Captain…one U-boat kill is confirmed.”

A weak cheer was raised in the mess. Most thought to themselves that it was a costly price to pay.

The Chief Mate handed over a roster he took from a waterproof envelope with all the names and classifications of both the merchant and naval crews aboard his ship. The heading at the top of the typed page, in larger print, was S.S. Cape Flattery, the vessel lost in the fog a day or so back.

The Primrose’s crew was working feverishly to care for those most in need according to the severity of their wounds or exposure. Blankets were passed around and the treated men were escorted to a very confined emergency berthing area with several sets of many-tiered racks chained up against the bulkhead, which, when lowered, appeared to have less than a foot clearance separating each rack.

Ned motioned for the Chief Mate of the Cape Flattery to follow him to his Captain, who was sitting, hunched over, clasping Ned’s coat around his shoulders. Ned offered the old man a cup of tea. “This was the first thing this crew offered me after they fished me out of the drink and it seemed to bring me back to reality. Like they told me, it’ll do you wonders.”

“Son…nothing can relieve the frustration I’m feeling. I was entrusted with the finest ship afloat. My crew was all dedicated old time merchant seafarers. Even the Navy boys showed tremendous promise and took great pride in being assigned to the ‘Cape’…but sailing in a slow convoy was like tying an anchor to a thoroughbred racehorse. The loss of so many men, it just was…not…necessary.”

*****

In the following days many alerts and reported sightings of periscopes and imaginary torpedo wakes kept all the crew on their toes almost to the point of exhaustion. Some reports had validity and caused extreme patrolling by the convoy escorts.

One incident had two ships leaving the convoy during the night to go on their own. They were chased down and were forced to return at the threat of being fired on by the escort leader. Word had drifted down to the Primrose that the Captains of the two cargo ships had suffered severe land-based air attacks during previous Murmansk runs near the same location that the present convoy was entering and felt that the safety of the crew and vessel was their first priority. They wanted to take a more circuitous route away from the German bomber bases at Tromso and Kirkenese.

No one disputed their logic until Lt. Perry let everyone know within earshot that he considered their action a selfish, undisciplined act. “Their armament,” he reasoned, “along with keeping the rest of the ships close together, offered the best defense for all ships with their concentrated anti-aircraft fire.”

“Proof” of the Primrose’s Captain’s reasoning came within hours. The Commodore fired his cannon and signal flags were run up, “Begin zigzag on my hoist.” As underlined and capitalized in the Commodore’s convoy list of instructions, the second hoist ordered all ships to “change course left thirty degrees.” The planes were several thousand feet up; out of the range of most of the convoy’s light Ack-Ack weapons, and all bombs fell harmlessly away, doing no damage. Unfortunately, that was just the first wave of six bombers.

The Commodore ran up another command, “cease zigzag” another hoist was run up on the other spreader to “steer due north.” He apparently was taking the convoy away from the air group’s point of origin. If the planes came from Tromso, a German airbase on the northwest coast of Norway, then that would indicate the enemy planes were almost at their extreme operational limits and the convoy might be able to steam outside their limit.

The change of course as ordered was not a column change but each vessel was to act immediately and independently on his command in an oblique maneuver, so they would wind up following behind the ship that was to their port side.

What really worried everyone was that the Germans now knew where the convoy was and how many ships there were. It was no longer “if” they would attack, but “when” and they didn’t have to wait long for “when”.

This time six more planes came in just above the wave tops. Every ship opened fired with everything they had as each plane sought its target. One plane was firing its cannons as it swooped in on a trail of splashes that led up to a new Liberty ship, the splashes turned to flashes, finding their target and raking the ship’s house and bridge. Just as the JU 88 rose to clear the Liberty ship’s cargo masts it released a bomb that found its mark, and a large eruption of water mixed with smoke sent debris high above the ship.

Dark smoke came out of the stack and the engine room fiddly skylights just aft of the stack, indicating damage within the engine room. Men were seen scampering over the already slung-out lifeboats, uncovering them.

The Liberty ship’s guns were sending up a heavy barrage. Hitting the planes was important but showing the enemy their enormous firepower should make the pilots think twice before planning another strafing run. Primrose also showed her ability to put up a decent barrage. The price was heavy for the enemy; three planes were destroyed. The rest broke off and headed for home.

Primrose approached the Liberty on that ship’s damaged starboard side and hailed the people on the bridge wing, “How serious is your damage…do you need assistance?”

“The engineers are returning to the engine-room to assess the damage. I’ll give you a report when they get back to me,” responded a voice from the Liberty’s bridge, and then added, “I do not require assistance at this time.”

White smoke was now rising out of the skylights, indicating someone was getting a handle on the fire, and a small jagged hole was visible just above the plimsol between the waterline and the rail. Steam was shooting out of the stack with a tremendous roar, probably from the lifted safeties on the boilers; no doubt a result of the fireman or water-tender being unable to tend the boilers. The ship was no longer under propulsion. The engineers had evidently shut off the steam supply to the engine thinking that the ship was mortally damaged; wanting to stop the propeller from rotating should she go down. She was losing headway and began to lie sideways and roll in the troughs. Men were forcing something that looked like a large wad of canvas or a mattress through the hole from inside the ship.

Flags reported that the Liberty now falling quite far astern of the convoy had raised the “in need of assistance” signal hoist. A British Destroyer circled the Liberty ship and was communicating by semaphore signal flags. The Primrose maneuvered close to the Liberty and was ordered, by the Destroyer, to provide a tow and render any assistance the damaged ship requested. “Confirm!” came the order from the Destroyer.

Ned thought he heard the skipper mutter under his breath “pompous bastard” and drew his own conclusion that the Destroyer’s skipper must have been Royal Navy and not an Volunteer Naval Reserve such as the Primrose’s Captain. He chuckled as he thought to himself, so much for the skipper’s personal discipline and control theory.

As the skipper brought his ship alongside the Liberty, he hailed short cryptic instructions “This is the HMS Primrose. We have been ordered to take you in tow…I will send you a messenger line by Lyle to your foredeck…You will bend on your longest mooring line…add on more line as necessary…We will bring it aboard our ship then attach our towing wire…You will winch your mooring line along with our wire and secure the wire, as you deem best…Any questions?”

“I understand,” replied the Liberty’s master, “If you could just head us out of these troughs, my engineers say they can make revs. We take on water every time we dip our beam-ends. Our generator flat is badly damaged…the fire is under control…we are on the Diesel stand by. We have casualties…they are being tended to.”

A loud report, not unlike the roar of cannon, was heard as the Lyle gun was fired sending the messenger line on its way, uncoiling itself from the round bale as it arched high overhead and disappeared between and beyond the Liberty ship’s masts.

For the moment U-boats were not a serious concern but getting caught by enemy aircraft in this almost slow motion scenario was uppermost in everyone’s mind. The Liberty ship was still digging out its mooring line, which seemed to take hours as Sub-Lieutenant Barstow kept time with the sweep second hand on his watch. Everyone on the upper bridge kept watching Barstow, he would hold up two fingers then three…. after fifteen minutes the Liberty started to winch aboard its mooring line and the Primrose’s wire.

Finally, after twenty-five minutes, the Primrose started moving, paying out her towing wire over the heavy pipe strong-backs at the stern as she moved ahead of the big ship. In the meantime the convoy was nearly ten miles distant and almost over the horizon. Two Corvettes could be seen prancing around in the neighborhood as if playing tag with some unseen objects. It was comforting to know they were nearby.

Slowly the bow of the big ship turned as the wire almost stretched taught and then sagged back down in the ocean. A sigh of relief, almost audible, drifted throughout the crew; even though they were making less than two knots…they were moving.

Everyone on the Primrose kept looking back at the Liberty for signs that she might, with some luck, get underway on her own. No smoke and no steam were promising signs and after twenty minutes of towing the wire no longer came taught, in fact Primrose was clipping along at five then six knots. Finally an Aldis lamp started blinking from the Liberty (forbidden while in convoy) saying that they were under their own power and thanked the Primrose for all her assistance. At the end of the message they added, “We’ll see you in Murmansk.” They then let the tow wire slide to the depths of the ocean and raced on ahead, tooting the whistle as she sailed by.

*****

The sixteen, eighteen and twenty-hour days of constant alert were taking their toll on the Primrose’s crew. Most just rolled out of their sack to go to action stations, to eat or to go on their regular watches, then they crawled back in the sack at the first opportunity to catch what sleep they could…. only to be called out again at sunrise or sunset, the two times of the day when most attacks, either by U-boats or aircraft, frequently occur. The crew was approaching the point of complete exhaustion, and what they were able to do was almost in an automatic response to their rigorous training. The ‘Cape’s’ survivors were given privileges to a mess table after some volunteered to help in the galley and others volunteered to help the black gang down in the engine-room. Lieutenant JG. Roemer, Commanding Officer of the US Navy’s Armed Guard, volunteered his men on the guns but the skipper was reluctant to allow them to participate other than to pass ammunition. His reasoning being that his crew was well trained as a team to man the weapons

A following sea developed as the convoy approached a change to a more easterly course while still keeping well offshore from Nordkapp. The lumpy seas were spreading out the convoy and, as the ships were unable to control their yawing, the convoy became so widespread that the Commodore released some of the faster ships for the short run on in to Murmansk. Already there were sightings of Russian Naval escorts and their aircraft, displaying a large red star, buzzing about in the area. Again Primrose took to the task of rounding up her straggling herd of unruly sheep…. just as a flight of Kraut bombers arrived.

This time the planes had a shorter distance to fly from their occupied base at Kirkenes, Norway, which was about a hundred miles distance. Captain Pedersen of the Cape Flattery, being of Scandinavian decent, had corrected everyone on the pronunciation of Kirkenese saying the Norwegians say what sounds like “Shirkneese”.

The Commodore hoisted the “Commence zigzagging” pennant. The outer convoy escorts made up of Destroyers, Sloops and Corvettes came in for close support of the convoy and began to put up a heavy wall of fire.

Primrose and her three other close-in support and rescue vessels were mixing among the now ragged scattering of ships trying to establish some sense of order. A lone fighter-bomber made a run from abeam of Primrose, kicking up sprays of water until its cannon projectiles began finding their mark, starting from the bow and ever so slowly working towards the stern. Explosion debris was flying everywhere; men could be heard screaming above the aircraft’s roar and the blasts of the cannon’s fire. In a short period of only five to ten seconds unbelievable damage and carnage was done to the little Primrose.

The bridge phone rang at the after helm station. Ned answered, taking the headset from the badly wounded signalman. The voice commanded, “Mister Barstow, report to the bridge, immediately!”

Ned responded, “Mister Barstow is badly wounded, as is the signalman and many of the Number Two gun crew. We need help fast!”

Lt. Roemer, of the US Navy Armed Guard, and his crewmen rushed aft to give help to the wounded and take over the unmanned gun; firing as if it were their normal assignment.

Ned noticed that the ship was maneuvering somewhat out of control. The phone rang and again Ned answered. The voice on the other end gasped, “You now have the con,” and the phone went dead.

Ned called to some men on the deck below, “Is anyone below in the emergency steering compartment?”

“It is buttoned up manned and ready, Sir,” someone hollered, “How is Mister Barstow?”

“I’m sure he’ll make it,” Ned answered, “I’ll send headings through the voice pipe until the skipper can come back and take over.”

Ned went to the after-command station, removed the hinged lid and blew into the voice pipe that lead down into the lazarette emergency steering compartment; he then put his ear to the bell of the voice pipe and heard, “Petty Officer Randall at the helm sir.”

Ned called for a twenty-degree right rudder and immediately the ship veered to the right as the Petty Officer called out the compass heading, confirming that the people below were receiving the directions. “Rudder amid-ship,” Ned ordered. The response was almost immediate, “Rudder is amid-ship…heading is steady at zero-nine-zero degrees, Sir.”

The ship held steady on a straight course. Ned’s view, however, was obstructed by the deckhouse and bridge and he couldn’t see what was going on up ahead of the ship; but by calling for different compass headings the ship responded by wiggling just enough allowing him to see ahead.

Ned uncapped and blew into the engine room voice pipe then put his ear to the flared end, listening.

“Engine room here,” came the response.

Ned advised the man at the other end that control of the vessel was now at the after-steering station.

Primroses second in command, Lt. Bridges, came aft and officially relieved Ned. Flags, meanwhile, was entering all the activity in the log, along with a description of the chaos that was evident around the Number Two gun station.

Ned observed a salute and handshake between Lt. Roemer and Lt. Bridges. He could only surmise that it was some form of an unwritten sign of recognition and appreciation between the two Navy men.

Steam had been escaping ever since the attack and Primrose’s progress was noticeably waning. When pounding was heard coming from the side of the ship Ned asked one of the survivor Engineers from the Cape Flattery, who had come up on deck for a quick breath of the cold air, what all the pounding was about.

The engineer replied, “We’re driving plugs in all the holes in the hull. Sometimes we have to drive in a steel drift to shape the hole so that it can take a wooden tapered plug. This ship is sure thin-skinned and she’s pissing streams of water everywhere. Both boilers were damaged. The Chief is going to shut one down. They appear to know what they’re doing and have it well under control.” Ned helped lift Lt. Barstow to his feet after he received his emergency first aid. He and a seaman helped him through the passage way and down the ladder into the PO’s mess where they were met with a scene reminiscent of just after the Cape Flattery incident.

A surgery was in progress on one of the tables and a familiar voice called out, “We need type ‘O’ blood, now! Who has type ‘O’?” The man wearing a surgical mask turned to Ned and asked, “Do you have type ‘O’ Mister Dominy?” Ned recognized the Scot brogue, the first man to greet him and offer that cup of tea that did wonders.

“I do!” Ned replied, “Who will take the blood?”

“I will,” said the Scotsman, “I’ll give a direct transfusion. The man has lost a lot of blood but I think with your help we’ll have it under control. Lay down on that stretcher next to that man over there while I get set up.”

Not wanting to look at the grisly blood-covered human being lying alongside him, Ned closed his eyes and prayed silently to himself that his blood might help the man to survive.

Scotty, the senior sick bay attendant did his best to stem the flow of blood from the injured man and performed the transfusion. He told Ned to lie quiet for a while to regain some of his energy. Ned glanced over and recognized the now cleaned arm and tattoo of the man who had received his blood. It was Charlie, the Cockney loud-mouthed cribbage player. Ned grinned and closed his eyes again, “Won’t he be pissed to know that the blood of a Yank is now flowing in his very own veins.”

The Scot showed that he was a capable medic. He communicated a comforting attitude as he saw to the needs of the injured men, encouraging them and offering each man a “cuppa” along with, “It will do you wonders.”

Feeling somewhat weak after giving the blood, Ned left the crowded mess to go to his cabin and relax for a few moments, or at least until the next attack, which was sure to come. On his way to his cabin he was amazed at all the damage in the wardroom and officer’s cabins. As he wandered about the mid-section of the ship he thought how lucky it was for any of those who were able to survive.

Ned decided to go topside for some fresh air, as he climbed the ladder to the wheelhouse he was confronted with a scene of total chaos. A hole in the forward bulkhead of the house, large enough for a man to walk through exposed the three-inch cannon that was now a grotesque shape of useless metal, as if a shell might have exploded in its barrel or breech. His heart ached for the poor devils that had been in the vicinity when the explosion occurred. And what about those commanding the ship, “Where are they?” he muttered, shaking his head.

Several seamen were clearing debris from the decks; others were throwing live ammo and spent casings over the side. Ned returned to the wheelhouse went down the ladder and thought he would pay a visit to the Captain. As he approached the Captain’s cabin a seaman on guard with a heavy ammo belt and side arm informed him that no one could enter the cabin. Ned asked if he could speak with the Captain for only a moment. The guard’s only response was, “That would be impossible.”

Making his way down the passageway to his own cabin, Ned tried to open the door. It wouldn’t budge; kicking and beating it with all his body-might was to no avail. He finally managed to kick out the lower panel then got down on his hands and knees and peered in to see that the lockers had fallen and were now jammed against the door. It would take some doing to unclog the mess and he was in no physical or mental condition to tackle it.

Ned went to the after steering station and met with Lt. Bridges and Flags, informing them of his experience at the Captain’s cabin. The two men pulled Ned aside, out of earshot of the seaman standing by the exposed emergency con.

“I am hoping to keep this from the crew until this crisis is over,” confided the now new commanding officer. “Lieutenant Perry was killed…. along with our gunnery officer, the Coxswain at the helm and the communicator. I had the Captains’ body placed in his cabin for the time being. Lieutenant Barstow is badly wounded and may not be able to return to duty for some while. We also had causalities in the engine room and you’ve seen the crew’s mess. It is like a London infirmary after an air raid.”

“There are capable officers among the survivors of the Cape Flattery who would be willing to step in and help if they were given the chance. Lieutenant Roemer is Navy he understands your regimen, look how he and his men relieved on the pompoms.” Ned stated this as a suggestion only, knowing that the new CO would now have to make decisions that must satisfy the scrutiny of his own superiors.

“I have been in communication with the Liberty and they are willing to take all survivors aboard. We will transfer after dusk when there are still traces of daylight; I’d say about twenty-two hundred. The wind and sea should be calm enough at that time so we can transfer directly ship to ship. I would appreciate it if you would go below and inform and prepare all the survivors for the transfer.” Lt. Bridges instructions were clear and precise.

Ned thought the new CO was being somewhat cold, but only until Flags pulled him aside and explained, “If we, as a ‘British’ ship, were to deposit you men as survivors on the dock in Murmansk or Archangel without proper identification such as seamen’s passports, country of origin, or other means of ID lost when your ship went down, your chances of getting repatriated soon would be slim to nil. and the Ruskies could even try to make you pay for your food and lodging out of your own pocket. However, if you enter any Russian port aboard an ‘American’ flagged ship and you are an American citizen they can’t stop you from returning to the states, post haste.”

These circumstances had never entered Ned’s mind, nor had he ever heard anyone mention any events pertaining to what Flags had just explained. Once he understood, his respect for Lt. Bridges grew immensely. Ned went below and passed the word around of the coming transfer and the reasons behind it.

While Ned was below he stopped in the hospital and asked the Scot medic about Charlie’s condition after receiving his blood.

The Scot responded, “He’ll pull through; possibly he’ll even get pensioned. When I told him that a Yank’s blood was now pulsing through his veins, all he could say was ‘aw bloody shit!’ ”

***

It was nearing the time for the transfer of the survivors to begin. Primrose was closing on the Liberty very cautiously to prevent any unnecessary damage to either vessel. The Liberty had large fenders and cargo nets over the side and there were several Jacob’s ladders dangling from the rails. Block and tackles were hanging from the pipe davits that were normally used for lowering the ship’s accommodation ladder. The davits would now haul aboard, in baskets, those too injured to make it up the nets and Jacob’s ladders. The baskets resembled Stokes Litters; a basket in the outline of a large man, tubular framed, with wire mesh, in which a patient could be strapped for safety and ease of transporting up and down ladders or hoisting to another ship or dock.

Many of the survivors were gathering topside; some were displaying bandaged wounds from their original ordeal in the loss of their ship and others were showing wounds from the more recent strafing attack. They were very fortunate that the Liberty was heavy laden, with little freeboard, making it a short distance to climb up to the deck.

Ned was saying his goodbyes to the crew and especially Flags and Scotty, who had been escorting those strapped in the litters. Scotty handed Ned an envelope with his recommendations for treating the worst of the injuries. Flags also handed Ned an envelope that he told him to read when he had a chance. He shook hands and disappeared below.

The transfer went well, more than anyone could have hoped for. Five of the badly wounded were taken to the Liberty’s officer’s mess so they could be watched over until an already over-crowded sickbay could be set up to receive them. Everyone else sought spaces wherever they could. Some went aft and down into the spaces near the magazine and after-steering compartment, others holed up in the engine-room machine shop. Some of the Liberty officers allowed their counterparts to use their cabins and bunks when not in use. The Armed Guard took care of their own and shared their all.

The following morning many of the original survivors remarked that as thankful as they were that the HMS Primrose rescued them they found it much more comfortable aboard the Liberty. This consensus was reached mainly because of all the unpredicted maneuvering the little ship went through doing her assignments.

Ned joined with several officers on the bridge as the convoy entered the so-called ‘safety’ of the harbor at Murmansk, just as an air raid was in progress. Little damage if any was reported. The Harbor Pilot passed it off as, “Just another nuisance raid.”Far outside the anti-sub net Ned saw a trawler. Looking through some binoculars he thought he saw Primrose…. and that reminded him of the letter from Flags. He dug the crumpled envelope out of his pocket; tore off the end, drew out the folded single-page message and read:

Ned,

Seldom in the last two years have I strayed more than a few paces away from my skipper, Lt. Bridges, and fate chose that one moment to call me away. Our two families were very close. The war has taken a good man and, for me, a good friend. He confided in me that he enjoyed the conversations he had with you, as did I, and that they helped him to have more respect towards the United States Merchant Marine.

Goodbye and good luck. “Flags”

James Richards, Leading, Petty Officer Yeoman (Signals)

A mist clouded Ned’s eyes as he thought of the many appreciative crewmen aboard this Liberty who had never heard of the trawler escorts or knew of their duties until they had to learn the hard way of their unheralded contribution to many seamen’s survival.