PEASOUP ON A POTATO PATCH

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

PEA SOUP

on the

POTATO PATCH

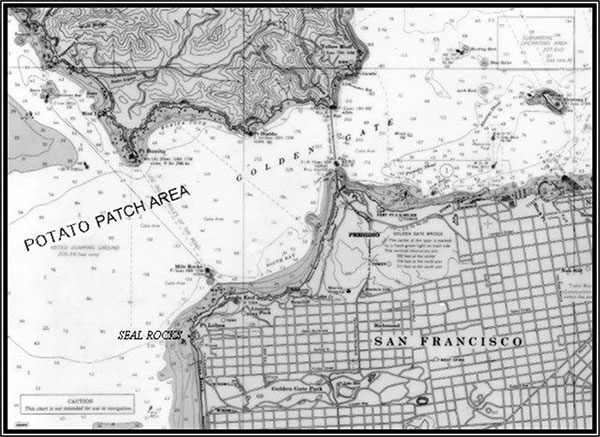

No, it’s not a menu item and it isn’t about food. But if you have ever sailed out of, or around, San Francisco Bay you should be familiar with the term “Pea Soup”, and you would certainly recognize the name “Potato Patch”, a large area on the left side when approaching the Golden Gate from the sea with its confused and bumpy waters.

Both of those terms, as told in this story, left such an indelible mark in my memory that I sometimes shudder when the thought crosses my mind and the scene again becomes all too vivid.

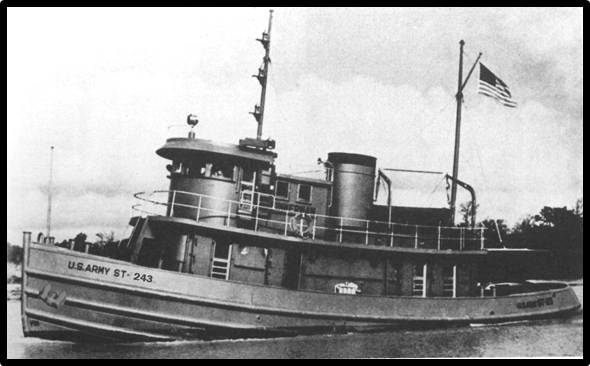

Monterey Bay in the summer of 1944 was a flourishing fishing port. It was also host to the large Army Training Center at Fort Ord, just to the north of town. Our purpose for being there was to hook on to two barges loaded with deck cargo of heavy duty army construction equipment that was too large for rail, truck or land transport destined for the Oakland Port of Embarkation, then to be loaded on a ship.

Being civilian crewmen on an Army ST (small tug) didn’t endear us to the Officers in command of this very formal military training center. Everything had to go by the book; signatures had to be affixed, but only after chasing down the responsible Officers. Manifests had to be checked and double checked, and all of this caused quite a delay to our getting under way for the estimated eight to ten hour trip. Our only critical period of the trip was to clear the ASW (anti-submarine warfare) nets before dark on entering beneath the Golden Gate Bridge. Otherwise we’d have to cruise offshore until daybreak.

Even with the late start, it was decided it was better to be on our way than to have to hassle with the system another day. We had both tows strung out behind and very little sea to speak of and the 600 HP Enterprise engine perked along beautifully.

According to our dead reckoning we showed five to six knots without any effort. We had just passed Santa Cruz in the late afternoon when a grayish-white solid wall started bearing down on us. It appeared as if a gigantic wave was about to engulf us. The seven of us who were in the wheel house couldn’t believe what we were seeing. And then it swallowed us up; a cold, damp, solid fog bank so dense you could hardly make out the barges strung out behind us. The fog soon became so thick we couldn’t see the bow stem from the wheelhouse, and a breeze was carrying it at a fast pace. Needless to say, this event put a crimp in our scheduling. We started reducing the engine revs and began sounding the horn at the proper intervals.

We continued to reduce our speed until we were barely making headway. We took in the towing wire to shorten the train just in case another vessel was in the vicinity. We had a choice of anchoring now or going on ahead hoping to come out at the other end of this thick fog bank. The skipper poured over the charts and decided to proceed until we were certain that we were out of the normal shipping lanes. Adjusting for our reduced speed, we plotted our last bearing fix and set a course for Pillar Point, a supposedly safe sheltered anchorage a short way up the coast, above Half Moon Bay.

Reaching the supposed destination by the running time and course plotted, we began taking soundings with the lead line and found a sandy bottom and decided to drop the hook. We continued with sea watches, ringing the bell at the proper sequences. After a while we began to notice an increase in the swell pattern.

During the night we felt uncomfortable with the thought that the anchor might be dragging, induced by the tows behind, so we payed out all the chain to give us a longer scope, which would give the anchor a better bite on the bottom. The skipper kept the main engine running at its slowest RPM’s and frequently telegraphed the engine-room to engaged the shaft in spurts to relieve the strain on the anchor. Unfortunately we could see nothing to help us determine if the anchor was even holding, our continuous lead line soundings indicated there was plenty of water.

The 4-8 watch has to be the longest of all the watches. On the evening watch daylight fades until darkness takes over. The morning watch starts dark and then the sunrise creeps up so slowly you think it’ll never get light. The only good portion of the watch is the relief for chow in the evening for dinner and in the morning for breakfast.

This morning was different. I came to the bridge searching for whatever was out there; I saw nothing. I climbed to the top of the wheelhouse for a look around. The binoculars didn’t help at all; I couldn’t even make out the barges. I did hear something that worried me though, the booming sound of the sea breaking on rocks or the beach….there was no denying that sound. I could feel the radical rise and fall of the tug as large sets of swells went past us, and then a few moments later I heard what I thought were waves crashing on the beach. At least I hoped it was the beach, as opposed to the large rocks and cliffs not far from this area.

I decided to call the skipper and was about to knock on his cabin door when it was slung open.

“Did you feel that?” He yelled just as another set of swells went by, followed by several more. “We’d better get the hell out of here!”

I told him that was the reason I was about to wake him.

After calling all hands to stand by, he ordered the engineer to increase the shaft turns and the ship sprung to life. Darkness had given way to the early morning haze of light but the fog was still with us.

We started retrieving the anchor chain. Three of us were in our foul weather gear but that didn’t help much because the bow dug into each swell. Solid water was coming over the stem and up through the hawse pipe. The windlass was taking her time retrieving the chain, making a clinking sound as each link bedded into the wildcat. We must have had well over 2 shots of chain out (one shot=15 fathoms=90 feet), and bringing it in as slow as it was going would take all morning. We were sopping wet and freezing operating the anchor windlass so we asked the skipper to have the engineer speed up the main engine so the power take-off would work the windlass faster. Then everything quit; both the winch and the main engine. The bow dove ever deeper into the on-coming swell, almost causing the swell to turn into a breaker as she went off our stern and on towards the barges strung out behind. I looked over the side and the chain was vertical, the anchor or the chain must have fouled on a rock or some other obstacle on the bottom.

I cranked the brake handle down and then disengaged the dog clutch to the winch to relieve any bind on the power-take-off. When the next set of swells came the slipping brake caused the chain to pay out on its own. I tightened the brake down harder, and threw over the chain stopper but the chain still payed out. I called for a pipe-wrench to use as a cheater on the hand-wheel, but the drag of the barges was too much for the brake on the windlass.

The air-injected engine coughed and fired for only a few turns a couple of times and then totally died. We waited a few moments as the auxiliary, now hooked up to the air compressor, was building up enough air pressure to crank the main engine over again. After what seemed an eternity we heard the Engineer injecting air to the engine, choo choo choo choo, in rapid succession as each cylinder tried to ignite. Then came that beautiful chipuka..chipuka..chipuka… There was no denying that rhythm….and the engine was off and running. The skipper engaged the prop shaft to assist breaking whatever was fouling the anchor on the bottom by powering the tug over the chain. This was a very risky maneuver, especially with the tows behind us. We over-rode the chain and tried pulling, then drifted back, but the chain-stopper was worn so much it couldn’t take a bite on the links. The grabber and brake couldn’t hold the strain and straightened out the grabber. The swells were increasing in size and frequency and we could hear the waves pounding on the beach, or rocks, behind us.

The moment of decision was upon us; “shit or get of the pot”. Should we run the chain out and lose our only anchor, or shackle and wire-clamp the barge towing wire to the anchor chain and then set all adrift. The bad part of that thought was that we didn’t know how far off the beach we were after the anchor had dragged during the night, and that we could lose some very important equipment if the barges were indeed that close to the beach.

The decision was left to the Captain and he decided to run the chain by removing the pin in the chain locker. That, in its self, was a dangerous task to have to physically climb into the large dark and damp tank-like chamber, move the chain aside until I could find the welded bale and shackle, and then with great effort unscrew the rusted shackle pin. When it was over it was easier than I predicted.

Once we were underway we stayed on a relatively safe but slow course in open water hoping for the fog to clear.

To be under way in a fog is risky business at best, but with barges strung out behind, it leaves a vessel no time or running room to maneuver should you hear another whistle out ahead, and we were hearing plenty of whistles and horns. We would stop the engine for silence in order to better locate where the horns were coming from. We would give the proper horn blasts to tell the other ships that we were towing; hopefully that would inform them to steer clear.

Our eyes kept playing tricks on us. We imagined seeing large dark masses off both sides and even tried to convince one another on lookout of what each of us “thought” to be a ship just a few hundred feet from us. There were three of us, including the skipper, on top of the wheelhouse, a man on the wheel, two men in the engine room to answer the telegraph bells, and the cook making coffee and sandwiches and bringing the food to those on duty. We were wet, cold, tired and scared to death, praying for the fog to lift.

We tried the radio direction finder but the stations that were powerful enough for us to get a bearing on were those that had moved their transmitters to other locations for security purposes. We couldn’t recognize the other radio beacons for they were coming in over the receiver weak or disrupted because of static caused by the dampness.

This was our first excursion outside the Bay. Usually we were on short runs inside harbor, from Fort Mason to Oakland and all the wharfs along the Embarcadero, with an occasional run to Sausalito, and when we saw fog start drifting through the Gate we would head for the nearest wharf and stay put until we could safely navigate. If we did get caught out on the Bay, many sounds were familiar and they would usually let you know where you were. The foghorn on Alcatraz was a good example.

By staying in open water the skipper felt as safe as anyone could hope to feel in our situation. If he could hear horns on either side of us then he knew we were in clear water….or those other ships were in serious trouble.

When you are in a dense fog your only communication with the rest of the world is by sound. You become very conscious of each horn or whistle; they each have their own distinctive characteristics. One off to port gurgled just prior to blasting with her deep bass sound that was so low you could feel the reverberations in your chest. Another tug was off to starboard with a tow heading south. She must have been Navy because she was moving along at a good clip, her speed indicated she must have had Radar or was using some new navigational aid. Ship traffic was surprisingly heavy, even for the entrance to San Francisco, but because of the dense fog we didn’t actually see a single ship.

Something happened that we thought would end it all for us. We heard it first, seals barking up ahead, and then silence. We shut the engine down and all was quiet except for a few horns and whistles off in the distance. Then we heard the barking again, and then once more it stopped. Just on a lark I thought I’d try a few barks to see if the seals would respond, a trick I learned while Commercial Fishing, and did they ever! It sounded like a whole colony of them, and all barking at once as if my barking had insulted them. This scared the hell out of us, as the only rocks in the area with seals were at Seal Rocks just offshore from the Cliff House or out near the Farallon Islands. Either way it would have meant that we were way off course, and therefore lost. A moment of panic set in. If we turned to the right we’d wind up on the beach at Flieshackers. If we turned left we were sure to go on the rocks at the Farallones.

We continued to drift, watching our stern for any sign of the barges and keeping an eye out on the towing wire so as not to foul our prop. Then we saw them. About twenty seals were fighting for space on a gigantic log, half submerged and floating free. The log had evidently been driven down from up north by the last storm. We didn’t have any way to destroy the hazard and just hoped that we would get clear from it without any damage, which, thank God, we did.

Ground swells are large bodies of water that are unable to make up their minds which way they should move; there is no pattern to their motion whatsoever. As we continued on a northerly course we could feel the change. A current suddenly began coming from the direction of the beach and the bouncing began. The swells increased in size, one moment we were in a hole and the next on top. Had there been a wind you would have said it was the start of a storm. Normally a seaman can anticipate the movement of his ship and allow for the diving or rolling, but not during a situation like this. Every step was like stepping in a hole, not knowing if there was a bottom or not. The snap rolling got to most of us. I had never been sea-sick in my life, but it was starting to get to me then and there.

Finally we felt a breeze over our stern and the fog started lifting. We could make out both of the barges behind us, but saw no sign of land. The ground swells had told us where we were, which was right on top of the Potato Patch bucking the current on the approach to the entrance of the Golden Gate.

Of course, being the “old salts” we all were, to anyone that asked us how our trip had been, we just shrugged and said: “Same old thing….just a routine trip”.

A LABORSAVING MECHANISM BEFORE

THE INTRODUCTION OF GEARED OR ELECTRICAL POWERED MOTORS.

FOUR TO EIGHT MEN, PUSHING ON BARS INSERTED IN THE PIGEON HOLES AT THE

HEAD WOULD HAUL IN ANCHORS AND OR

TRIM THE BRACES ON A SAILING SHIP