OPERATION MULBERRY

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

Notice rough sea at bottom of photo, then a first row of concrete caissons, followed

by a second row of sunken ships (corncobs) and then the calm waters inside the

Mulberry Harbor.

OPERATION

MULBERRY

A little known episode, not publicly acknowledged, was the participation of civilian Merchant Seamen during the Normandy invasion. Many were involved in one of the most secret of all secrets in World War II. Code named operation “Mulberry’’ and ‘‘Corncob’’, the formation of artificial harbors off the beachheads to protect the landings.

“Mulberry”: orderly lines of large concrete caissons placed end to end by tugs, most of which were crewed with civilian merchant mariners and civilian seamen of the U.S. Army Transportation Service. Tug crews of both the U.S. and British Navies along with crews of several foreign flag vessels received recognition for their participation. Civilian seamen, who did participate in that secret event, waited nearly 45 years to be recognized as “Veterans of World War II” and without any benefits.

I received an Honorable U.S. Army Discharge (without benefits) for my participation at Normandy and additional service in the Southwest Pacific.

“Corncob”: ships that were no longer useful because of their age, or otherwise damaged beyond repair, were sailed or towed, placed in position and then scuttled by their crews while receiving cannon fire from the German shore batteries.

As I recall now, 60 years later, our crew had no idea of the importance of our assignment or what that assignment might be. Only after the invasion started did we learn of its code name and the function it was to play at Normandy. To this day I don’t believe the ship’s officers were informed of “Mulberry” until long after its execution.

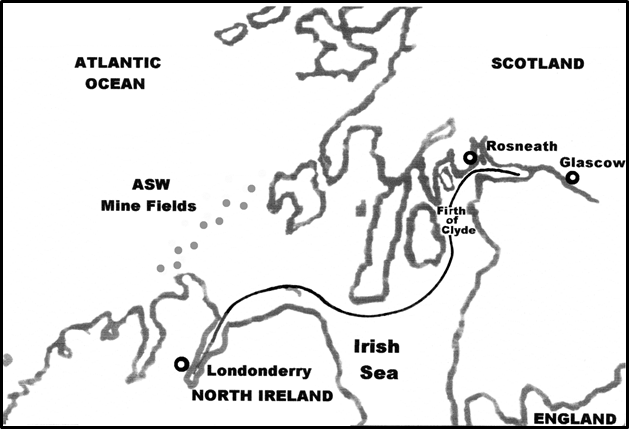

Our destination was a military anchorage at Rosneath, on the north side of the Clyde in Gare Lock across from Helensburg, to await our turn to pick up a large concrete caisson being readied near Glasgow. The caisson was built at “John Brown’s”, the same yard that launched the Queen Mary which, by the way, was just coming up the Clyde behind us to Greenock, no doubt to discharge her troops.

Tugs were everywhere; all sizes both steam and Diesel, wooden and steel, some with British flags, but many were American. We were informed that since we were late arriving that another tug was assigned our tow, and because we had success bringing in the Greek freighter, “Monopoly”, we were assigned to tow a vessel down from waters north of Scotland. Our Captain, now a Norwegian an ex-Swede was familiar with that area and the fact that we were a steam tug, compared to the smaller diesel tugs who were also awaiting tows at Rosneath, we were able to withstand the cold and heavy seas.

The deck crew was issued what were called “tanker suits”, made of fine waterproofed corduroy with a wool liner, and had hoods attached with a zipper. We could tell we were in for some cold weather duty. We also took aboard another officer. The crew could never figure out if he was “The” skipper or a pilot, or what his duties really were. His uniform was dark blue and had three jagged gold braid stripes with a diamond on the sleeves. While on watch we took our orders from our officers. The new officer conversed fluently with our Captain in Scandinavian but spoke English the rest of the time. He was always on the bridge but didn’t stand a watch.

We departed our comfortable haven during a nasty rain squall and sailed down the Clyde toward the unknown. We headed north between the Hebrides and on towards the Shetland Islands. The seas were rough and the angle we were forced to steer did not make for a comfortable passage. About every third swell would bring green water over our bows. It was almost impossible to hold a steady course and the helm took forever to respond….and when it did, the magnetic compass would spin past the course like a bat out of hell. At the time our Gyro-compass was malfunctioning so holding a true heading was almost impossible. I wasn’t a navigator but the chart table was behind and off to the right of the helm and it was not unusual for the helmsman to glance at the progress of the trip from the charts. We were using an aeronautical navigational chart which was new to me as it was without land outlines.

The mystery surrounding our activities deepened the further we got into our mission. The radio was continually blaring out odd, coded messages like, “Mister Jones, take your dog home”, or “Lady Love your bed is made”. Messages would come over the radio in a dull monotone; short cryptic sentences. Occasionally when a message was broadcast both the Captain and our strange officer would huddle at the chart table, laying out bearings with angles, parallels and dividers.

We were approaching some small islands when an English Corvette intercepted us, blinking his signal lamp rapidly. Our new officer used the small hand-held Aldis blinker lamp responding equally as fast, and then the sleek warship took off in a hurry. Every time a helmsman came off watch the rest of the crew would grill him for any bit of information. I don’t even think the other officers were informed as to what our sail north was about, other than the original “retrieval” mission.

We finally entered a sheltered cove in the islands where several trawlers were at anchor. Here our mysterious passenger departed in a launch that came out to meet us. We didn’t anchor; we just turned around and headed back to Rosneath. During the trip back all sorts of theories evolved as to why we had been sent north, the most likely one being that a ship must have broken down going to Murmansk, and a salvage tug got to her first. The unfortunate ship must have been under an Army charter or we wouldn’t have been involved. Or…did we really go to that “most secret of all secret places” the harbor of Loch Ewe, the staging area for the North Atlantic and Murmansk convoys.

On our return we steamed up the Clyde, past Rosneath, Helensburg, and on to the “ROCK” at Dumbarton almost ten miles downstream from Clydebank where the huge concrete box-like barges were built.

A harbor tug passed us the towing bridle attached to a 200 foot long by 40 feet wide box. Riding high in the water, her blunt forward profile didn’t offer an easy tow; she began wallowing all over the place from the very beginning.

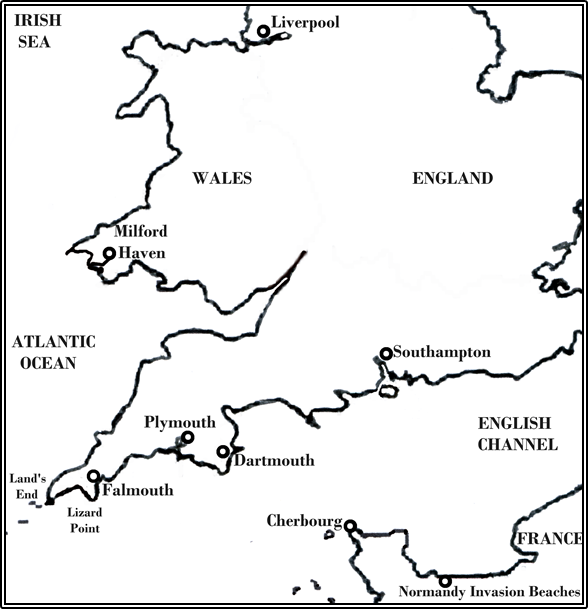

We had a slow but uneventful trip around Land’s End and then on towards Southampton. Somewhere around Cowes, on the lee side of the Isle of Wight we were approached by several small harbor tugs. They took our tow and disappeared to the west.

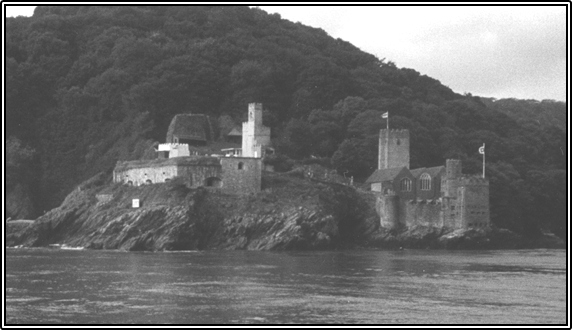

We were next assigned to a quaint and most beautiful harbor at Dartmouth. You wouldn’t even know it existed if you were sailing up the coast, as you have to enter the mouth of the Dart River, go past a huge castle like fort on the left, go left up the channel then veer right. Off to the left was the very picturesque town of Dartmouth where we tied up to the rock quay (pronounced key) at the edge of a pleasant park.

Ancient fort guarding the entrance to Dartmouth Harbor.

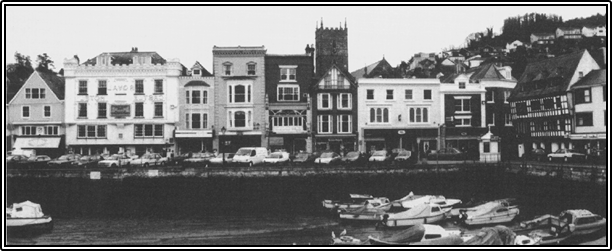

Townsfolk were sitting on park benches watching our approach. My memories are filled with pleasant thoughts of the community and its people. A short distance up the river was the Royal Naval Academy. Across from Dartmouth, at Kingswear on the opposite shore, was the largest assemblage of landing craft imaginable; LST’s, LCI’s and LCT’s loaded with troops and vehicles.

Staying aboard ship as gangway watch the first night was a lucky stroke for me. I noticed the signal tower blinking for our attention so I went up to the signal lamp to respond. It was a message for the skipper to go to the port director’s office. I notified him, then returned topside to continue communicating (via blinker) with the WREN signal gal. We talked for quite a while; I learned a lot about her and the dating customs of her group….a pre-attendance to an afternoon social (tea) and introduction to her duty-mates. A reciprocal invitation to tea was mandatory. All dating was with an escort only, walks on the roads and only in groups. Very very stringent.

I went below to beg the Captain’s permission to allow a visit of the signal group the next day. He suggested tea and said he would offer the invitation after going to the port director’s office. What an opportunity! Officers and men scurried around to make themselves and the ship presentable. Table cloths came out of storage, cookies were baked…the whole works. Everyone started brushing up on proper protocol; after all, we were going to entertain the Royal Navy. It was an event I’ll never forget and the highlight was that I met and dated a very lovely Scot lady.

Dartmouth as it was in 1994 just as it was in 1944 or in 1904; it has never changed.

We had the good fortune to stay tied up for several days. About 10 o’clock in morning we would play music over the loudspeaker to the people in the park and we soon had quite a few people sitting on the benches listening to the latest American hits. Afternoons and evenings the crew would congregate at the local pubs to drink sour apple cider, ale and stout, and sing old songs with the local villagers. Of all the places I visited during the war, Dartmouth holds the warmest memories.

We were on our way north towards The Clyde to tow down another concrete Caisson when we received orders diverting us to Liverpool to pick up a large British self-propelled floating crane to be delivered down to Milford Haven.

Liverpool is the main entry into England for Irish emigrants and many settle in the area to work in the shipyards and the large manufacturing plants up the Mersey River towards Manchester. An army base with a large contingent of Irishers must have been located nearby and released them all for liberty.

The dockworkers at Gladstone Docks told us we could get all the booze we wanted at the Lime Street Railway Station if we liked rum, and rum and coca-cola was the big thing at the time. As we walked into the station we were hustled from all sides, liquor, sex, anything you could possibly want. A couple of Tars cornered us and were asking one pound ($4.00 American) for a half pint of their rum ration (if they were caught they would do big time) we got them down to half their asking price. We each downed our half pints straight (as they wanted their bottles back) and feeling no pain, we started off looking for fun wherever and however.

Outside the station was a growing throng of several hundred uniformed men who seemed to be in an inebriated state. They were dancing, marching, singing and mock fighting and having a grand old time. As we tried to cut through the crowd someone grabbed us and said the party was just beginning and for us to join in as, “Today is Saint Patrick’s Day, the wearing of the green, the one day of the year the Limeys let us have Liverpool!!” So we marched up and down the streets joined arm in arm thirty to fifty wide, singing and yelling. Oddly, no one bothered us. Even the Brit sailors off a docked aircraft carrier seemed to enjoy the shenanigans.

The large British crane we were to tow had a crew of 15 men and was escorted by a Motor Gun Boat, a Motor Torpedo Boat without torpedo tubes. We noticed the obvious physical handicaps of some of the crew of the MGB. They were very friendly and explained that the British Navy didn’t always discharge their wounded service personnel if they were capable and volunteered for limited service.

We recounted our previous trip about our mysterious Commander Skye. The MGB men knew of the man, as they had worked with him before, and said that he was in command of a major salvage operation. It seemed that the military wanted to salvage as many old ships as they could and bring them south. Part of our mystery was solved regarding the mysterious officer….but WHY were they bringing all the salvaged vessels south?

We made it as far as Milford Haven and spent several days at anchor waiting for a storm to blow itself out at Land’s End, then found out they wanted the crane towed on to Southampton. When the storm passed we began our trip. As we rounded Land’s End we encountered huge following swells much like those we had crossing the Atlantic. We made it around Lizard Point and were working our way towards Falmouth when one of the crane’s main boom-guys let go. The boom started swinging from one side to the other. Luckily we found shelter behind a headland before any real damage was done. Repairs were made and we went on to deliver the crane to a harbor across and down the estuary from Southampton without further incident.

It was early evening when we anchored and heard gun fire from across the bay. German planes were coming in just above the water top and the gun crews of the ships at Southampton were firing with everything they had. The only problem was that no one seemed to care or realize where their expended shells were winding up. We were ducking for cover while trying to secure the anchor as shrapnel fell all around us, and some were pretty big pieces. It’s a wonder no glass was broken or that anyone was seriously injured.

Shrapnel was found all over the decks the next morning. The whole incident couldn’t have lasted more than two or three minutes at most, but by the time each man on our tug had told his own terrifying tale of “Friendly Fire” you would have sworn it lasted the whole damned night!

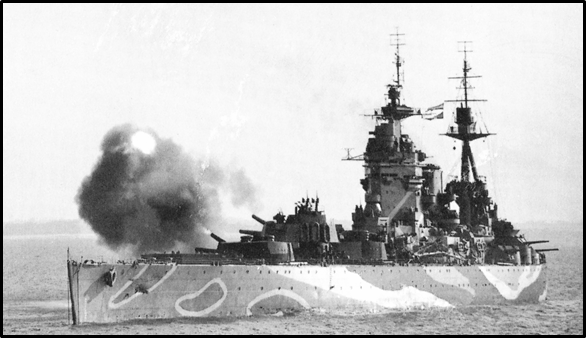

This south coast of England had so much activity, both ashore and afloat. From Falmouth to Portsmouth there must have been at least eight major harbors and all were filled with every type of ship and barge that could be imagined. On one trip to Plymouth we went into the back bay passing by the H.M.S. Rodney, by far the largest battleship I had ever seen. She was very impressive and our pilot explained that she was built under a set of international restrictions that reduced her original size by at least one-quarter, otherwise she would have been the largest warship afloat and that was the reason for her three turrets forward and only one turret aft.

HMS RODNEY

Several nights after returning to Dartmouth we heard the heavy roar of many engines laboring in the harbor and by daylight not a landing craft was to be seen anywhere. We soon found out where they had gone. In the middle of breakfast we got an emergency message to leave immediately at flank speed for a beach just up the coast from Dartmouth, called Slapton Sands.

It is hard to describe all the activities of the ships jammed together just off the beach. Some were leaving after discharging their cargos; others were awaiting their turn to go in. One LCT launched her stern anchors too early, tried to back down, sucked up her anchor tackle, and went into the beach sideways bouncing off other boats on shore. An LCM directed us to the damaged landing craft, took our towing wire then assisted with making up a bridle so we could tow the LCT off the beach. All the while other landing craft were loading or off-loading equipment and personnel around us as if we weren’t even there. We, along with the help of several other boats, refloated the troubled LCT. They cast off our wire and the LCM’s pushed her ashore so she could off-load and then load up again. We wound up towing her back to Dartmouth.

We made another run to Southampton, and while lying at anchor, sounds of very heavy droning began. Rain clouds were low and heavy so we couldn’t see the flights of heavy bombers, the noise kept up the whole night. Standing anchor watch was boring, especially when it drizzled. Being unable to take shore bearing fixes to make sure our anchor was holding made me more observant of the ships in our vicinity, and many of them were active that night. The Mate on my anchor-watch was also the radio operator. At certain times radio messages were directed at particular vessels on a certain frequency. It must have been our turn because the Mate received a message and pushed the alarm bell waking every one up. We upped anchor and were on our way within a few minutes to Yarmouth, some 20 miles away.

No one in any life-time had ever before seen an armada such as we saw in the English Channel that day. Every conceivable type of vessel: attack transports, cargo ships, destroyers, landing craft and patrol craft of every shape and size, were under way….By morning it became obvious they were heading in the direction of the French coast, and we were going the wrong way….or so we thought at first.

On approaching Yarmouth a small motor towing launch escorted us to a weird contraption that resembled a spider or an Erector set on top of the water; what appeared to be several high legs attached to a large rectangular-bodied barge. We picked up her chain towing-bridle and along with several other tugs headed out in a southerly direction. A Coast Guard SC came alongside and we took on an officer as a pilot, we towed at three to four knots all that day and into the late evening. We were buzzed several times by friendly planes and came upon a cluster of ship and boat activity. We later found out it was the invasion staging area. Several tugs took our tow; then we reversed our course and headed back across the channel.

During my trick on the helm, the watch officers were discussing a report that had just been received about an LT tug similar to ours hitting a mine and sinking with all hands. It didn’t take long for that news to get to the off-watch crew. I went below for a cup of coffee and the mess was crowded with all hands, many lying on the deck with their blankets. As I went down through the fo’c’sle to the head I didn’t see one person brave enough to sleep in their bunk. From that moment on we doubled look-outs and the fear of death was suddenly on all our minds.

The seas were rough and choppy going back towards Southhampton. The armada continued with its huge towing project. This was an operation of monstrous proportions. The naval Lieutenant confirmed that the invasion was on. We had already guessed that…. but where? He also said the crab-like contraption we had just towed was one of the foundation anchors for constructing the eighth wonder of the world.

We arrived back at Cowes and were told that over half of the concrete boxes had been towed away. We pulled along side a small harbor tug and took a bridle of one of the cement caissons and were on our way again. We noticed that “Monopoly” was gone. Tugs were every where. It seemed like everything that floated was being towed towards the beachheads.

Our first trip over we heard and felt concussions but we passed them off as bombing or heavy gun fire from the ships closer ashore. We were pumped up sky-high with excitement and somewhat disappointed that we didn’t get close enough to see anything. On our successive trips, with the breakwater forming up, all the activity was inside the sheltered areas. LST’s were unloading on barges directly from their bow ramps and the trucks took off towing trailers of material. The new harbor was so busy there was no room to maneuver. A PC came along side and we lost our Navy pilot.

We received orders to sail for Falmouth to bring a string of barges to the invasion area. This took us out of the area of activity, but we welcomed the opportunity to take on fresh stores and maybe get in a short liberty. However, the weather wasn’t cooperating. The seas were building up and the wind was almost at full gale. This storm couldn’t have hit at a more critical time. We were bucking our way along the coast towards Falmouth when the radio traffic began telling a story of mass destruction. Every frequency was reporting the same scene over and over, no longer using communicator’s language, but plain English. Requests for help from every one at the Mulberries….

The date was June 19, 1944.

We reversed course to assist another tug that lost her tow in the same general location as we were. The call came late in the afternoon but by night fall we hadn’t located the tug or the barge. We never found out if they recovered their tow or what happened to them. We could pick any number of calls to help, and most of them were coming from the beachheads. It sounded like the whole breakwater was being torn apart. Ships were reporting collisions and sinkings too numerous to keep track of. We rode out most of the storm in the lee of Berry Head a headland not far from our home port of Dartmouth.

When the storm allowed, we notified our operations that we were available and were told that the materials on the barges at Falmouth were needed more than ever since the beaches were a disaster. After picking up our barges and delivering them, we assisted with the clean-up and attempt to re-align the breakwater. At low tide some of the vessels had been driven a half-mile up the beaches due to the combination of the high tides and high winds.

The assault forces had driven inland enough to secure the beaches, and after the storm enough shelter remained behind the damaged breakwater to continue landing the much needed forces and supplies.

In the English Channel mines were

the bane of all small vessel seamen.

The German mine in photo is on

display in the park at Dartmouth.

The last towing job that I was involved with before going home for re-assignment to the Pacific was to tow a string of barges to Cherbourg. We laid at anchor all night outside the Outer Breakwater with three barges of ammunition, waiting for the minesweepers to clear a path leading into the outer harbor.The Germans had done a good job protecting their interests at Cherbourg when they had mistakenly thought it would be one of the main points of the invasion by the Allied forces. All night we could hear and feel the concussions of the mines exploding as they washed up on the breakwater. Early the next morning a launch with our French harbor pilot aboard was cruising back and forth several hundred yards out to sea from us, blinking instructions for us to come out to where he was. We upped anchor and followed the launch, the pilot came aboard, introduced himself, and congratulated us for being the first Allied ocean-going ship to enter Cherbourg. But most of all he congratulated us for surviving our stay that night in an unswept mine field.

As we entered the outer harbor we were met with a flotilla of small power boats, many appeared to have been pleasure boats at one time. We timed our entry at the highest part of the tide so the smaller boats could drive the barges up on the concrete embankments where army trucks and small cranes were waiting.

During the hour or so stay, several explosions occurred in the inner harbor, the French Harbor Pilot told us that the Germans had laid mines with time delayed fuses that were set to go off many hours or even days later, thus dissuading divers to go down to disarm them.