OCEAN LIGHTER

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

OCEAN LIGHTER

It is now….as it was then, hot as hell with enough humidity to swim in. Time hasn’t changed the weather, or I’m just not as acclimated to it as I was nearly 60 years ago. The beautiful green foliage has recovered its territory that we so ruthlessly cut and or bulldozed away so long ago.

Time has altered my memories. I thought by returning with my wife and first-hand describing the scenes as I remembered them that it would be exciting, but hell I don’t recognize anything. It’s like visiting a strange place I’ve never been to before and only proves that you can never go back again.

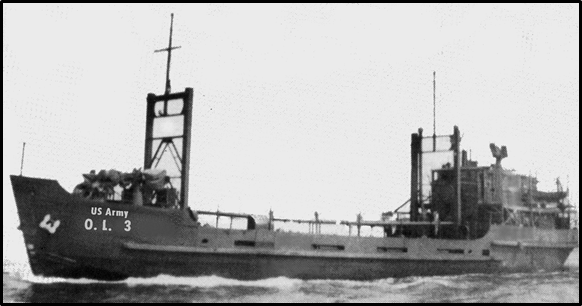

Most likely the warriors that charged the beaches have memories they wish they could forget, but out of it all I’ll bet even they had moments they’ll cherish forever. Such are the moments I remember as a crew member aboard an Army Transportation Service vessel. A steel 120 foot Australian built Ocean Lighter (resembling a North Sea Trawler but was really not much more than a self propelled barge), she had a speed of 10 knots flank, loaded or empty.

The ship had a mixed crew of five Aussies, two Americans and a Chinese mate who went by the name of Louie Chin. We were all picked from a cadre pool of allied seamen preferring to sail on the “Little Ships” that plied the coastwise and inter-island waters of the South Pacific.

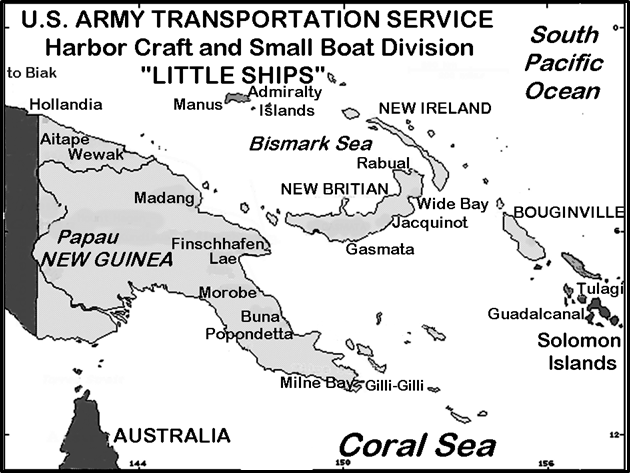

Our sailing or service area was from the island of Biak, a small island off the Northeast coast of the New Guinea part of the Netherlands East Indies, to the Northern Australian coastal town of Townsville and every port, harbor or indentation along the New Guinea coast. We hit them all, and wound up physically hitting the Great Barrier Reef.

Our Aussie cook was hard to describe; scruffy beard, no shirt, but always had an unclean (not filthy) apron tied tight just above the nipples on his chest, and a cigarette dangling from his lips with the ashes always dropping in the food as if he was doing it deliberately to flavor his culinary creations of bully-beef, dehydrated potatoes and onions, or dried eggs and powdered milk. But his pièce de résistance was biscuits, our only form of fresh bread. After a while we didn’t even mind the little black specks (weevils). In the beginning I wondered why the crew would always hammer the biscuits on the table. It was to wake the buggers up to give them a chance to crawl out. No coffee… just tea….his brew was so strong it would stain the cups with a crust you couldn’t scrape out….and then the Aussie crewmen would add two or three teaspoons-full of the thick, rich “Double Eagle Brand” condensed milk. They even put that stuff on the biscuits as if it was a dessert treat. Yuck!

The Captain and the Chinese mate never ate in the mess. We all suspected they had contacts ashore to get a better supply of food fare than we ate. We had an eight man crew: Two deck officers, three AB’s, one engineer and one oiler, and of course the cook. If we were destined for an unsecured area like Aitape or Wewak, we took on regular Army gunners from the Ship and Gun crew of the 35th Transportation Corps to man our 20mm and .50 caliber guns. Fortunately we never had to use the weapons. The only time we could have used the guns they probably wouldn’t have done us any good anyway. The guys firing at us from shore were using much heavier artillery, and since we were running away and zigzagging as fast as we could, we couldn’t have reached them with our pea shooters anyway. Most of our cargo was loaded at the rear areas like Milne Bay, Lae, Finschhafen, or Madang and was destined for Hollandia or Biak. The war had just moved up to the Philippines but some hot spots still existed in our rear areas. I recall the 41st. Infantry Division made a lot of small landings, and after securing each operation would then regroup to form a safe perimeter, leave a few good men behind, and take off for the next operation. The bad result of that thinking was that the Japs who had hidden and had been over-run in the initial assault wound up starving and would desperately try to penetrate the small defense force left behind. These small security forces were the people that we supplied.

These perimeters had no docks, so most of the supplies were sealed in heavy wax-coated paper boxes which we tossed over the side, and were then floated ashore by the men stationed there. The same thing applied to the fuel in 55 gallon drums for the generators and vehicles; toss them in the water and the men would swim out and float the drums ashore. Even the replacements had to swim ashore after putting their gear in rafts. Drinking water was sent ashore in 5 gallon Jerry cans, they also had to go ashore on the rafts.

On one voyage of interest our orders directed us to Gasmata, on the island of

New Britain, but before we sailed our regular Captain had to go to the hospital for surgery. So, the Command at Finschhafen assigned a temporary skipper for the trip of maybe 10 days. The relief skipper was knowledgeable, young, and wasn’t afraid to get his hands dirty. I found out that he had plenty of sailing experience.

His father was an Italian fisherman who owned a Tuna boat out of San Pedro, California. His older brother relieved the father as skipper from time to time and he and his brother couldn’t get along, so he shipped out in the Merchant Marine, (Army Transport). While standing watches together he told me of his adventures in the Alaskan waters which I wrote about in a story called “ISCHIA”.

We were about two hours into the trip when one of the AB’s twisted his foot so badly that it immediately turned black and blue and swelled up. We helped him to his bunk thinking that if he elevated the foot it would relieve the pain. That also left us one AB short, so we divided up the watches of six hours on and six hours off, the same hours as the Captain and Mate always stood while at sea. My trick was 12 midnight till 6 in the morning and then 12 noon until 6 in the evening with Mr. Chin, our Chinese Mate. Several times during the watch, the Mate insisted on taking the helm and said that I should stay out on the bridge wing standing lookout. About 2 a.m. I started into the wheelhouse to offer to relieve the mate at the wheel, but he told me to stay out on the wing. I thought it strange….but hell if he wanted to steer the ship that bad, I wasn’t going argue. We didn’t have hydraulic steering, only manual, and it sometimes took all you had to keep her on course, so this was a real treat.

I normally kept my cigarettes next to the binnacle and I wanted to go below for a smoke, so I told the Mate I was going below for a few minutes and grabbed for the pack of Old Gold’s, knocking aside the other pack of smokes. At that moment the compass spun around like a top. After getting a butt out of the pack I went to return the pack next to the binnacle, but the mate wouldn’t let me and told me to get the hell out of the wheelhouse. I knew that the mate was upset at being passed over for temporary command, especially by such a young “kid”, as Mr. Chin called him. In the beginning the crew didn’t think the mate got a fair shake, but as Captain “kid” showed his abilities, well….

After a cup of tea and a smoke I went back up to the wheel house to offer to take the helm. He accepted the offer and this time I was on the wheel for the rest of the watch. When I relieved the previous watch the course was chalked on the black board along with any changes planned, and times of changes to be executed. The original course was something like 076 degrees. The mate told me to hold a course of 068 degrees, to compensate for a current set, an order which wasn’t out of the ordinary. The sea was calm, and the moon was very bright casting shadows in the wheelhouse. After a while the mate asked me to go below to get him a cup of tea. I was gone all of five minutes and returned with the tea. When I took over the helm I noticed right off a radical change in the pattern of the shadows during that five minute interval. While the mate was busy with the charts I swung the ship around to the shadow pattern as I remembered it had been before I left to get the tea. A full 030 degrees off. I kept it to myself and swung the ship back to the course the mate had ordered me to hold.

About 5 a.m. dawn was breaking and while I was doing stretches to stay awake I accidentally hit the packs of cigarettes stacked by the compass, knocking them aside. Again the compass spun like a top. Again I kept it to myself, placing the stack back just like it was before.

At 5:30 our new Captain came on the bridge, looked at the compass and went to the chart table. Mister Chin came in from the bridge wing and told me to go below and wake the 6-12 watch and the cooky. I did, and returned to the wheel. Both officers were scanning the horizon with binoculars. I thought I saw an outline of mountain ranges to the right of the bow, but that couldn’t be right. They should have been off to port. Anyhow a big discussion was taking place, and then it turned nasty. I could hear them arguing and almost coming to blows. Thank God my watch was over.

After being relieved, I went below for chow and climbed into the sack just as the engine sounded like it was in a hell of a strain and then quit. I went on deck just as they let go of the anchor. We were about a half mile offshore from a low lying beach with marshlands beyond. I asked the engineer what had happened to the engine, but he wasn’t sure….either a bearing froze or bad fuel. In the meantime, the two deck officers were still at it. Mr. Chin told the skipper that it was his (the skipper’s) bad navigation, and that we were lucky he hadn’t gotten us killed.

We had a big 6 cylinder diesel; direct reversing with a sailing clutch. With the clutch in neutral the engine ran beautifully, but engaged she wanted to die. The bearings were cool so it had to be something caught in the prop. I grew up in Malibu and did a lot of diving. I had several lobster pots out in front of our house on the beach and made my spending money selling the bugs to Los Flores Inn for 50 cents apiece. Many times instead of pulling up the traps I would dive down the twenty feet or so to the pots, get the lobsters (if any), and re-bait the traps. I offered to dive and inspect the ship for the problem. I dove in and immediately saw the culprit, a mooring line was wrapped as tight as possible between the prop and stern-bearing. I surfaced and asked for, and got, a sharp knife. It took a lot of sawing but it started loosening up. I started getting cold and tired; it took all I had to climb up the Jacobs ladder. I suggested that we try the engine in reverse. We started the engine in reverse and after resting I dove down again and cleared the remnants. They ran the engine forward, it sounded all right, so we hoisted the anchor and we were on our way. But our position along the coast of New Britain was not certain.

I should mention that Mr. Chin was a very talented artist. Everywhere we went he would sketch views of the profile of the harbor entrances, indicating the obvious navigational aids such as mountain peaks, cliffs and so on. And all this was done with color pencils; they were really works of art worth framing.

We finally made Gasmata, a small lagoon on New Britain, but we missed the landfall by 10 miles. After making the treacherous entry as waves crashed across the shoals on either side, we tied up to the docks below the Australian Military headquarters. Two formations of Papuans were assembling on the lawn of the drill area. They looked mighty impressive with their khaki tunics, and on the sleeves were inverted chevrons with a crown symbol at the top. One group had green lap-laps and the other had red lap-laps. All wore the bush hats with one side turned up. They looked cocky as hell, even in their bare feet.

The injured AB was taken from the ship and placed in the infirmary; the doctor diagnosed the injury as a broken bone at the instep and said that it should be put in a cast. We moved his gear ashore, planning to pick him up on our way back.

An Australian sergeant toured us through the base, pointing out the Japanese gun emplacements at the harbor entrance. Then we went through the Japanese hospital ward which had sloping cement floors towards the center with a walkway and gutter in the middle, and at the upper end of the slope were little wooden blocks with a notch carved out of the mid-section that the Japanese would use for their head rest.

Lunch….That had to be the best meal I had in months, curried lamb with rice, a fresh fruit chutney, loaf bread… and real butter.

We returned to the ship and started to rig up an awning over the cargo hatch. A carpenter fashioned a two-pot crapper which dumped through a scupper over the side, with a bucket on a lanyard for flushing. We stored four inflatable rafts in chocks. Next morning the Papuans started to come aboard, 24 of them with two Aussie sergeants. The troops wore only the lap-laps, and they carried a ditty bag, bush knife, bandoliers and Thompson .45 sub-machine guns and tooth-brushes.

We cast off and headed out through the shoaly entrance and past the rusting gun emplacements off to the port side. Questions were asked, but no one offered answers. Where were we going? Why the troops? What are we going to do with the inflatable rafts? Finally the young skipper called us together at the mess; the two Aussies were there. We were instructed not to communicate in any way with the troops, that they would stay at the hatch area, they had their own food and water, and needed no outside assistance. The sergeants said any questions would have to go through the skipper. You could tell that Mr. Chin was not a part of the plan; he seemed more pissed now than he had been before.

We stopped at Wide Bay for a few hours at an Australian Army camp controlling the land approaches to Rabaul. As we were anchoring, a launch tried to come along side but the Aussie sergeants wouldn’t let them get close, telling them to clear with their base commander. We couldn’t go ashore….All a very strange scene. We upped anchor and left Wide Bay a few hours later, heading almost due north and Rabaul was just north of here…Hmmm. I asked if I could change watches, telling the Captain that the mate and I couldn’t get along and six hours of his surly attitude was more than I could take. He agreed. Standing watch with the “kid” was interesting; we were from about the same area back in the states and went to many of the same places in Southern California. I could tell he was very familiar with this particular area as he kept telling me how to correct my steering by slight changes. He talked to the engine room through the speaking tube, calling for changes in the shaft revolutions. The Aussies were in the wheel house constantly, not saying a word. The skipper called for a hard left rudder, then reduced the engine revs just enough to make headway. The troops were busy gathering their belongings and getting ready….but for what? We were closing on the beach, too close for comfort, then we touched bottom. The engine was stopped and all was quiet.

The rafts were lowered over the side, gear was placed into them and our passengers were gone just like that, no noise, no yelling, just very calm as if they did this many times. We found out later that they did this operation about once a month. Rabaul, though neutralized, was still in Japanese hands.

We returned to Jacquinot Bay some 30 miles south of Wide Bay to deliver the cargo in our hold, take on water, go to a movie, and get tanked on thick, dark Aussie beer, the best ever….The next morning Captain “kid” wanted volunteers to launch the lifeboat and go on a little fishing expedition. He had all the gear necessary and I’m sure he had the knowledge to use it, having been raised in a fishing family back home. The Captain, Engineer, and another AB and I took off in the 18 foot lap-strake life boat, powered by a 19 hp Evenrude outboard motor. I was operating the controls and the others were looking over the side into the clear water, where you could see the sandy bottom and the colorful marine growth and rocks some 30 feet below. I slowed the outboard almost to the point of stalling the engine; schools of fish were all over the place. The Engineer nudged me, winked, and pointed to a glob of white putty with a fuse sticking out. As he put his cigarette to the fuse he told me to give the motor full throttle; the others were still peering into the depths. The fuse took and I jammed the throttle full as the Engineer dropped his charge into the water. The engine stalled and then stopped. I wound the cord, gave it a good pull…. nothing. The Engineer tried, but to no avail. I panicked! This was it! I yelled out that we were going to be blown up in a second or so. The Engineer shouted, “Don’t jump in the water or you’ll get killed!” just as the charge exploded. I was standing and it felt like someone took a healthy swing with a sledge hammer to the hull right below my feet. A mass of boiling water came to the surface and damn near turned us over. The AB fell forward at the blast; his mouth was bleeding from a cut in his upper lip where his teeth almost drove through. The Captain was trying to untangle the teeth from the lip and the poor Engineer just sat in the stern seat cussing to himself, apologizing to the others and chewing me out for not operating the outboard motor properly. We noticed the water level had risen in the boat considerably and we tried to bail but we couldn’t keep up with the water coming in. We weren’t too far out so we took off our clothes and slipped into the water pushing the boat towards the shore. A couple of nice size fish came to the surface and I tossed a few in the boat. Under the seats were buoyancy tanks to store survival stores. We made it to shore just as a patrol boat came on the scene curious about the blast. The Captain told him that we just dropped the anchor and “BOOM” we must have hit a shell or a bomb, causing it to explode. Quick thinking….The kid was OK. The patrol boat towed us back to our ship, but stopped on the way to collect as many surfaced fish as they could.

Our stay at Jacquinot was cut short. We headed back to Wide Bay and tied up to the only dock in the bay. We went ashore and drank more of that good Aussie beer. A few hundred yards north of the encampment were field artillery pieces nestled in dugout trenches with sand bags stacked all around. Half crews manned the cannons, always on the ready just in case the Japanese tried a Banzai attack. We went to the front and looked through the high powered field glasses but we couldn’t see any activity at all by the enemy. Come evening we cast off about the same time as we had left several days before, and resumed the same course we=d been on previously.

The Captain took the wheel for a spell and I went out to the wing and saw Mr. Chin down on the deck lounging. I thought it a good time to tell the skipper of the events that took place on our way from Finschhafen, how the compass spun when I moved the cigarette stack, and about the shadows changing so drastically. He was very interested in my story and asked many more questions than…I expected he needed to ask.

Everyone came on the bridge when they heard the engine slow down. We were coming close to shore in the same area we had before. We stopped and drifted, keeping our eyes peeled for the Papuan rafts. Stare real hard and you can imagine anything your mind wants. You think you see movement, rub your eyes and look again, nothing. It was a warm night with just a gentle breeze wafting, but the spooky atmosphere sent a chill through my body. I actually got cold. Were we too early? Were they late? Did they run into trouble? Were we at the right spot? Finally, after an agonizing time, we saw the rafts coming towards our ship. The skipper told the mate to release the stops on the cargo nets lashed to the bulwarks so the returning men could climb aboard. I counted four rafts and a lot of bobbing heads. Two men were lying in the rafts. I tried to count heads but they wouldn’t stay in straight lines long enough so I gave up. As they came along side the Aussie sergeant told us to stand aside, they could handle things themselves. I found out later that this group of Papuans were Regular Army serving as scouts, frequently behind the enemy lines severing communications, observing movements of both men and material, and just wracking havoc as needed to demoralize the Japanese. On this venture they went in to see if there was any build-up for an assault along the Wide Bay front. These guys weren’t short timers either; some had served since the first “War to End All Wars”. They had helped to stop the Japanese advances in New Guinea. One curious fact about these men was that they all had beautiful white teeth. They would brush their teeth many times a day, contrary to their culture. Most Papuans suck on twigs soaked in beetle-nut juice which rots the teeth and causes an addiction to its numbing and euphoric effects.

The entire group reported aboard and after all equipment was properly stowed, we took off towards Gasmata. The two injured men that arrived in the rafts had cuts on their feet, and one had a swelling in his knee, nothing serious. The two Aussies didn’t have much to say; it was just another patrol to them. I guess if you live it morning, noon and night, it becomes routine.

After discharging our deck cargo of men and picking up our injured AB, at Gasmata we were off to Finschhafen. The AB we had left behind found a lot about the background of the Papuans. I think it’s a shame no one publicizes such a brave and noble group.

Just before entering the harbor at Finschhafen, Captain “kid” asked me to read the log and sign it. “Good God, are you trying to get me killed?” I asked.

“Isn’t that the story you told me?”

“Yes, but it was done in confidence and you’ve added things I don’t remember saying. I’ll initial only those parts I said… OK?”

“Fair enough”, said the Captain. No sooner had we tied up to the dock when Military Police drove up and boarded our ship, commanding several of us to get into the truck. We were taken to Army Headquarters and to the CID offices. With me was 1st mate Louie Chin, the Engineer, the other AB, and Captain “Kid”.

Several officers were sitting at a table. The ranking officer was a bird Colonel. A Major was asking questions about the possibility of a magnet near the compass. I answered all the questions they asked and was taken to another part of the offices and sat for several hours. I felt like I was being held as a criminal. The Colonel came in and asked me to sign a statement which seemed essentially what I had told the skipper after leaving New Britain. I signed, and was taken to chow. What a feast they serve in a shore-side mess! After eating they returned me to the ship. No one ever explained to me what had happened but it was the last we ever saw of Louie Chin. We heard later that he was being watched for mailing military hardware after bribing the postal clerks at Madang.

Captain “kid” turned the ship over to our regular skipper, said his goodbyes, and was off. I heard about him many years later from family members who were customers of a company that repaired fishing boats. Our original skipper on returning from the hospital, told us that Captain “kid” had his own ship which had been tied up for repairs, and that it was now ready for sea. The trip we had just returned from with the Papuans was one of Captain “kid’s” normal duty assignments.

The Captain made arrangements to have a few improvements done to our ship. We scraped and suegeed the forepeak and after-peak tanks then painted them with a cement coating. Fresh water showers!! An Army welder came aboard, burned out a section of the pantry, installed a chiller box, and then re-welded the bulkhead like it had been originally. The pantry had been a dry storage area before and always in a clutter, so the welder then put in shelves that would handle the canned goods. Within a week we started living in style. Ice cubes for Kool Aid, no less. To top it all off, the Captain got hold of a washing machine…..with a wringer!!

The new refrigerator meant that we could get our full rations of fresh meat. Before, we could take only that amount we could roast or boil and then dip into melted paraffin and hang in the shaded areas about the ship. We usually wound up tossing much of it overboard, as it was quick to turn rancid in the hot climate. Our crew believed that the fresh meat and vegetable rations we were unable to take wound up being served at the Base Headquarters dinning tables.

We received orders to proceed to Townsville, in Queensland, Australia, and took on food, fuel and water. The Captain estimated a 4-5 day passage if we didn’t stop too often along the way. Right off the bat we were told to stop at Gilli-Gilli, an Aussie Hospital camp, in Milne bay. We took on a lot of crates and a bunch of boxes about the size of caskets. On any our northbound trips we would haul a lot of American caskets for the burial brigade, as they were clearing out all of the small cemeteries and sending the remains to Hollandia for shipment to Hawaii.

A day or so out from Townsville as we were approaching the Barrier Reef, using charts with notations such as, “12 fathoms (1825)”, “Wreck (1790)”, “Rocks (1923)”, “Blind passage no exit”, “Coral-Ledges Caution”. The Captain was a good navigator so we weren’t concerned until we ground to a halt on a reef ledge. We were doing all of three knots when we hit, but we went sideways and locked ourselves on it.

I wasn’t on watch so I don’t know the details for a fact, but from what I heard they spent an hour looking for the buoy just before grounding. The helmsman spotted it and headed directly for it, closing to within a 100 yards right before we went aground. The ship took an odd set, we heeled to one side and the bow was very high, causing the stern deck to go awash every time a swell would come at us. We secured the hatch to the crew sleeping quarters which were astern and below.

I’ll say this for the skipper; he tried every trick in the book to free us but to no avail. I was taking soundings on the starboard side away from the reef, but couldn’t find bottom at 120′. The skipper was just staring at the buoy, when all of a sudden he started cussing it and calling it every salty name he could think of. He called for every man on the ship to come up to the bridge and witness what had caused the grounding. I couldn’t see anything out of the ordinary. He told us to keep staring at the buoy; meanwhile he was taking bearings with the pelorus. The ship hadn’t budged an inch after settling on the reef, but that damn buoy sure was moving around a lot. Hell, she was floating free, dragging her chain and traveling wherever the currents took her. Some days later I was reading the ship’s log entries and came across the note “________ Buoy not at station, floating free. Witnessed by entire crew.” Of course this knowledge didn’t help get us off the reef, which came later that night.

I don’t know if the reef had a tide variance, or if a large swell freed us, but you could feel the soft easy rolling motion and you knew we were adrift on our own. We launched the life boat (now fully repaired), and proceeded to take soundings, but that didn’t help too much in the dark because the ship couldn’t maneuver with that quick of a response. To try towing the ship was out of the question as it would be like the blind leading the blind. While taking lead-line soundings I found a large area that had good depth and a soft bottom, so the Captain decided to anchor for the night. The next morning, bright and early, we were following the new mate who was in the lifeboat out ahead going back and forth through the obvious passages in the reef. The color of the water was changing from light aqua-marine to deeper shades of green, and then the blues and we knew we were free to continue the course to Townsville. Such was the life on the U.S. Army’s “LITTLE SHIPS”.