NORTH ATLANTIC CONVOY

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

Early winter 1944: A cold and windy New York City was not the most ideal weather condition for a Southern Californian lad (just arriving from the warm climes of the Canal Zone aboard an ocean-going tug) possessing only light warm-weather clothes.

The crew of our Miki-Miki tug decided to return to California on completion of their delivery assignment, but an opportunity for me to sign aboard a new large steel ocean-going steam tug heading for Europe was presented and seemed to offer more excitement and adventure than what another boring delivery job had to offer.

I met with the Captain and Mates of the new tug and with exception of the Norwegian skipper, the other officers were not much older than me. I guess it can be told now; all the officers were really Swedes but had to claim to be Norwegian before the US government would hire them. The officers seemed satisfied with my experience and had me sign the log. I learned that the bulk of the crew would be reporting aboard in the next day or so from Sheepshead Bay Maritime Service Training School. I was appointed temporary Bo’s’n; only because I was the first deck-hand assigned. Besides, there were a lot of last minute stores and supplies that needed to be loaded on board.

The crew’s quarters were forward through the mess and down a stairwell almost to the forepeak. There were twelve double-piped berths with mattresses, two high, six to a side, with two tables dividing the area. The head was just aft of the ladder: two pots, two wash stands and two showers; lockers were stacked alongside that bulkhead. The layout was clean, comfortable and efficient.

The crew’s mess was a long table with swivel stools on each side. Just opposite was the officer’s mess, and the only difference was the padded stools with arms, a leather couch, and a heavy curtain surrounding their area. The next deck above was officer’s quarters, bridge, navigational and radio areas.

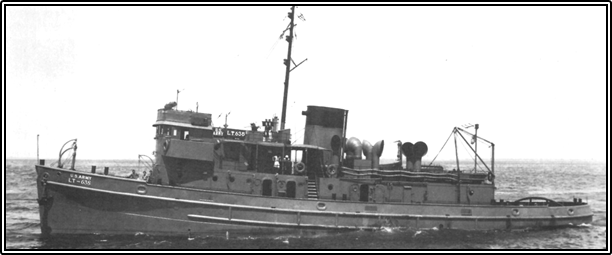

The L.T. was new. She was the largest class of ocean-going steam tugs constructed for the Army Transport Service. At 149 feet she was capable of going anywhere in the world, but her 1,200 H.P. Skinner Uniflow enclosed reciprocating steam engine didn’t quite do her justice. With a crew of 24 officers and men she was easy to manage under most circumstances.

The following day the new Maritime School compliment started arriving in trucks. All of the men were dressed in uniforms that were very similar to the US Navy enlisted personnel, with the exception of a blue hat instead of a white hat and square red arm patches sewn on their black peacoats, and all had, of course, the traditional sea bag slung over their shoulders. Oilers, Firemen/Water-tenders, then came A.B.s, Ordinary Seaman and Mess-men. The moment they came aboard everything became neat and orderly, bunks made, gear stowed and they all changed to working dungarees.

The weather wasn’t cooperating, drizzle and sleet, but we had a war to get ready for. Lifeboat drills, boxing the compass, fire drills, air raid drills, emergency maneuvering; the drills soon had the crew working together and we were rewarded with sporadic Cinderella liberties. I almost forgot that I was still a civilian.

An odd occurrence; two shipmates and I, along with girl friends were across the river at a cafe on Staten Island when a pair of Navy SP’s inquired if we were from an Army L.T. We told them we were. They suggested that we send the ladies home and get into their truck for a ride to the Brooklyn ferry, as our ship was there at the Army Port of Embarkation. Out of millions of people I’ll never understand how they were able to single us out.

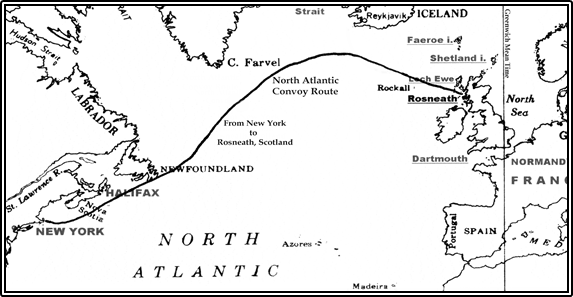

Sea watches had already begun as we reported aboard and I was assigned to the 8-12 with the skipper. We departed the Army docks and headed down river, I had the first trick on the wheel. We were bringing up the rear of a single file of ships until we cleared through the narrow opening in the anti-submarine net. It was an exciting moment, knowing that there were a lot of ships out there forming up for a big convoy and we were going to be part of it. It was mentioned in the wheelhouse that a sub would surely hit the jack-pot if he spotted this mass of ships.

When I relieved the wheel the next morning, I saw ships every where as far as the eye could see and I asked the skipper how many were out there. He said there were over 100 ships of all kinds in our group and that we could pick up another bunch on the way. It was unbelievable. What a mass of ships, all in columns from one end of the horizon to the other, and we were bringing up the rear.

The speed of the convoy was set to accommodate the slowest of the slow, 8 knots, or depending on the whim of the Commodore. Courses were changed by signal flags, with each ship repeating the hoist and then altering course or speed as ordered. A Canadian escort vessel was maneuvering in and out of the rows of ships at high speed, calling out, with the most obnoxious remarks, to those ships that would drift out of line or were lagging behind.

After leaving the Nova Scotia coast we picked up a cold wind and a following sea. We wound up with about 150 ships total. Tankers, not normally sailing in convoy, were off to the north side of the convoy. The further north and east we traveled, the larger the swells increased in size from crest to crest and depth of trough. The Greek freighter on our port would surf almost up to the stern of the ship ahead, then she appeared to slide down the back side of the swell into a valley and stay there for the longest time, then repeat the whole procedure over and over again.

While standing wheel watch it was interesting to watch the gyrations of the different ships. We had a Jeep Aircraft Carrier that couldn’t have launched a plane if it had to as she was yawing to and fro even worse than we were. The wind was blowing at nearly 50 knots; blowing the tops of the swells into large breakers. While off watch we found it exciting to go aft to stand in the towing-winch house and watch the stern dig into the sea….and just when we thought the sea would swallow us up with the curl of a gigantic wave, the ship would gently rise above it, then nose dive and when the propeller came out of the water the ship would shimmy and shake like a dog ridding water from its fur

Late one afternoon several days out, a signal came throughout the convoy to be on the lookout for subs. It must have been serious because the Commodore released the tankers and a couple of modern ships to go it on their own because of their greater speed. Another signal was passed to change the course at 2400 hours (midnight) with a major alteration of 60 degrees to the north. Fog was drifting in among the ships and soon only the ships ahead and to our side were visible. Later more signal flags were raised among the ships but we could barely make them out as it was getting dark and the wind was coming over our stern causing the flags to fly away from our line of sight. The consensus of the officers on the bridge was that the new order was to confirm the previous order (regarding the course change). It was forbidden to use the blinker light unless it concerned the safety of the convoy.

Like the ship ahead of us, we rigged a towing log with several hundred feet of line to drag a box-like float behind us that would create a plume of water resembling a rooster tail. The swells were still with us but the wind had moderated. Because of the poor visibility we were trying to stay as close as possible to the rooster tail ahead, and to do so we had to continually ask the engine room for more or less turns on the shaft as it appeared the ship ahead was constantly speeding up or slowing down. During my trick on the wheel a very dense fog bank engulfed us and I could barely make out the towing-log ahead. Then I lost it. We were blowing our whistle at the appropriate intervals as were the other ships. We doubled the lookouts, we speeded up, ran to the left and to the right….No ships. We could still hear the whistles but they were getting weaker.

The Captain yelled at me, “How could you lose them!” He was taking all his anger and frustration out on me as if the fog was my fault. I was relieved from the wheel and was ordered up to the monkey bridge to stand lookout and was told that I better damn well find the convoy. By now we could only catch a hint of the whistles way off in the distance. We weren’t lost. The convoy was! The Captain decided to continue with the last instructions he had.

Remember….I was on the 8-12 with the skipper, we lost the convoy at 11 p.m. and we were to change course at 12 midnight, hold the new course for three hours and then resume the original course. After setting the new course, I was relieved from the watch, went below to get a sandwich and sit in on a game of pinochle.

All hell suddenly broke loose. Whistles and horns were going off all over. We would heel over to one side then to the other. I thought sure the subs had found us and that we were trying to escape them. I made it up to the bridge in less than a minute (my assigned station in emergencies) and saw a ship was bearing down on us from the port side. Another was just ahead, and it looked like we had just missed one that went past our bow. It appeared we were going to run into his log-line at the same time the ship that went astern of us took our log-line. All the while whistles were blowing collision blasts (a series of rapid short blasts). What a nightmare! Fortunately, before we rammed anyone or they rammed us, we spotted an old “Hog Islander” that one of the mates had shipped on before. The mate knew her position in the convoy, so we adjusted our course to get back into our own position. We found out later that the signal we missed (which we thought was confirming the “Change Course” order) moved everything up by one hour and that put us smack dab in the middle of the whole convoy of ships when they resumed the original course three hours later. What a night!! and damned embarrassing too. The Captain and I weren’t nearly as congenial after that night.

We started taking a more northerly course and you could really feel it. A sweatshirt, turtleneck sweater, peacoat and foul‑weather gear could not keep out the cold. We wore long watch caps and cut holes in them for our eyes and when you breathed through it, ice would form from your breath. Decks were getting treacherous from icing. I would stand two hours on the wheel and then two hours lookout, usually on the opposite side of the bridge from the officer on watch, while the ordinary seaman and I swapped wheel tricks.

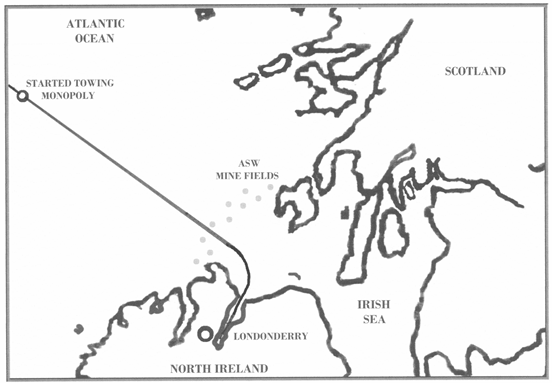

A Greek freighter, named something like M. Monopolis, (we called her “Monopoly”) had asked permission to drop out of the convoy as she was having engine problems and couldn’t maintain the pace. The Canadian escort vessel came along side and ordered us to retire with the ship in trouble, stand by, and if necessary rig up to tow her. The swells were still mountainous; we had been riding with the seas the whole trip. When the Captain decided to turn the ship around it was easier said than done. “Hard a port, full left rudder!” the ship came around but at her own pace. We were broad-side too, and just about to go into the next swell when the sea picked up our bow and shoved it back the other way and I had a full rudder going into the sea. We tried going full speed ahead and then turn, but no luck. The sea was much more powerful than we were. Dishes, pots and pans, anything that wasn’t tied down went flying. We had an after maneuvering station above the winch house and the skipper said he would control the ship from there. He said that I should respond with the helm as he relayed it to me by the rudder indicator. We finally made it around, but half the crew was prepared to abandon ship, thinking she might turn turtle on the next swell.

Few people know first hand of the force that the sea can generate. Going with the wind and the sea it will seem to be gentle as a lamb, but turn around and try to meet it head on, and it’s like taking on a charging elephant.

Diving into one swell then another was not getting us anywhere. We tried steering several points off without any improvement. Here we were supposed to be assisting a ship in trouble when we were probably more in need of help than they. Not enough power was the consensus of those in the wheel-house. What luck, after we spent nearly an hour trying to buck the sea, the “Monopoly” signaled to us that she was able to rejoin the convoy. I guess to her we didn’t look like we were having any problems. The skipper was pissed because the Greek ship didn’t even offer any “thanks” for our efforts.

The last day out old “Monopoly” quit again, (lost a blade on the prop or bent her shaft) and she signaled us for help. The sea had smoothed so it was no trouble to go back after her. Then the escort vessel came along side ordering us to get back in formation, and shouting on her hailer system that “No one has the authority to drop out without permission.” The Captain was mad and upset with the arrogant bastard aboard the escort and we returned to the convoy. About a half hour later the escort vessel came along side again, ordering us to go back to the Greek freighter and this time, “take her in tow”.

The “Monopoly” stopped their anchor chain, and separated it from the anchor, then took the messenger line we sent over by Lyle-Gun and we fed them larger and larger diameters of line tied to the clevis on our towing wire. They then attached it to their anchor chain, payed that out and we were under way. We almost caught up with the convoy just as they were entering the mine fields of the North Channel and the Irish Sea.

The trip took 16 days and the only entertainment was “Double Deck Pinochle”. I had never played the game before so lost around $100 to the “sharks”. I worked damned hard the whole trip across the Atlantic and wound up without a penny to show for it. Our original destination was Rosneath up the Firth of Clyde, in Scotland, to participate in a towing adventure that was to become one of the best kept secrets of World War II: “OPERATION MULBERRY”