ISCHIA

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

isle de ISCHIA

ISCHIA is an island of only 18 square miles, with a population of 30 thousand plus, and lies 18 miles off the coast of Napoli in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Because of her well publicized neighbor “Isle de Capri”, known as a playground for many wealthy tourists, Ischia is seldom considered for more than a quick glance in her direction except for those who know of her or were born there.

There are few places on this earth, including my home town of San Pedro, that I know any better….even though I have never been to Ischia, or for that matter, to Italy.

My mother, father and older brother came to America shortly after the “War to End All Wars” in the early nineteen twenties, at the urging of uncles on both sides of the old families who had already migrated here.

Having family already established in San Pedro was the primary motivation. Fishing and all its environs were major factors, add to that a similar climate to that found on Ischia, it took little else for many Italian families to uproot and travel with all their worldly possessions to California.

Until I entered Catholic school when I was about five years old, I thought I was living on Ischia, Italy. My parents, aunts, uncles and cousins spoke of nothing else when they came to our house to visit.

I don’t know at what period in life I found myself feeling a bit different from the older folks. Maybe it was their old country habits or it might have been a language barrier, for they refused to try to speak English. It was always, “this is how it was in the old country and that is how it will be done here”. They were never willing to try new methods or deviate from old traditions.

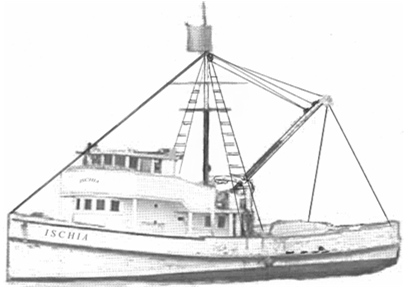

When I was about ten years old my father took me fishing on his sixty-foot Lampara-type seiner boat named ISCHIA. She was built along the lines of fishing boats found along the west coast of Italy. I lasted two trips. He was so demanding of me, cursing every move I made, in Italian, and seemed to enjoy embarrassing me in front of my older brother and the seven-man crew. These episodes began to alienate the relationship between the three of us.

Uncle Luigi was the eldest of my fathers’ brothers. Everyone considered him to be the Patriarch of our family of “Ischiadons”, as we were often referred to, for he was instrumental in encouraging all our families to come to America. And it is true that he adhered to the old country traditions as much if not more than anyone.

F/V ISCHIA

Aunt Anna, uncle Luigi’s ample rosy-cheeked wife, was a mother to everyone; she and her three daughters were the most active busybodies of our large family. They were always involved in arranging church activities and get-togethers. It was as if their sole purpose on earth was to make everyone dance to Aunt Anna’s music.

Uncle Luigi and Aunt Anna lost a son during the Great War. Instead of grieving over an empty grave they built and donated tributes to the church and community in his name. Their whole life seemed to revolve around the memory of my dead cousin, Giorgio.

A fact known only by his fishing boat crew was that Aunt Anna bossed Luigi as if he were her lost son and not as a husband, causing him to be the first boat to put out to sea and the last one to return. Many a time Luigi would stay aboard with some excuse that the nets needed mending or the winch needed repairing just to keep from going home to a house full of nit-picking women.

The depression of the mid-thirties affected the fishing industry as severe as everyone else and especially those of us that were considered foreigners. Our saving grace was that we so-called Ischiadons and Sicilians were tight knit families and weathered the slump by consolidating our resources and disposing of items that drained the finances. They formed a co-operative who acted as agents to buy and sell the catch and to pool a fund by charging a share of each catch to insure its members against most forms of losses. The boats purchased food and fuel from the Co-Op and expelled the few slackers that only took and never contributed.

Uncle Luigi asked my father if he would let me crew with him on his new boat during one summer vacation but without asking me first. I didn’t want to go but when the family says “do it”, you do it without asking any questions. I must confess the life of a fisherman is far from a romantic adventure no matter how hard a writer may try to set the scene. Stinking fish, working all hours without rest and when you do get a break you flop in your bunk with fish slime and its stinkin’ odor all about you….only to be rousted out again in two hours or maybe ten minutes. The fish won’t wait and you have to work fast when they do show up, for that’s the only reason that you’re out there.

F/V GIORGIO BOY

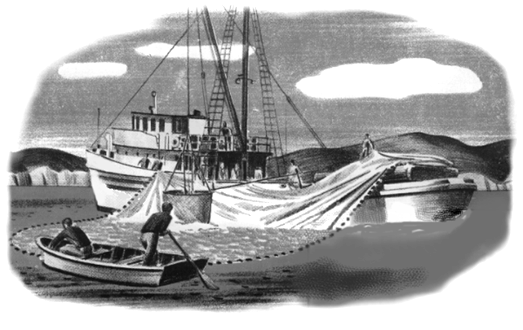

NOTE: Man on vessel handling long pole and brail makes ready to scoop Sardines from pursed net and dump into fish hatch when bottom of brail is tripped open. Meanwhile men in skiff, having already transferred open bight of net to vessel, now keep corks from going under. Man on turntable at the stern flakes net as it is hauled aboard.

The fishing community heard that there was good money to be made fishing for Halibut and Salmon up in the North Pacific around Alaska. During our slack fishing season a couple of the sturdier boats from San Pedro decided to try their luck by going north. Uncle Luigi’s boat GIORGIO BOY was readied for the long voyage.

Families of the fishing fleet congregated on the dock, Monsignor Conigli held a blessing of the crews and boats, and tears flowed like good “Dago Red”. My father and mother came down to see us off but my brother Dominic was at sea on the ISCHIA chasing Sardines.

Uncle Luigi, a most patient man, took me under his wing and taught me coastal navigation and dead reckoning. I finally found a niche in fishing that really interested me. Most local boats don’t even use charts because the Captains know the local waters so well it’s as if road signs were posted in the middle of the ocean.

Our trip north didn’t keep us from making several sets on schools of Sardines that we were able to off load in Monterey. Since we wouldn’t be using the Sardine seine in Alaska we off-loaded our net, turn-table and skiff, to be picked up on our way back down.

Everyone on GIORGIO BOY addressed uncle Luigi as Captain and I did also. On the trip north he asked me to plot a course for Point Reyes Light which I took as a test to see if I could remember all the instructions that he had taught me. I don’t know if it was luck but we hit the headland right on the nose, after figuring in currents, drifts and sets, and wind. The Captain said I had a natural talent and started teaching me to recognize the different signs that appear on the water’s surface, like telling the difference between wind eddies and live bait, different bird actions and to also read the many shades of colors in the water and what they all mean.

Like my father, the Captain never learned to read or write English fluently and could barely speak it without a very pronounced Italian accent. Of course the hand, arm and facial expressions got the message across and sometimes a swift boot in the butt said it all. I became the navigator, mast-man and radio operator and I enjoyed every one of the challenges.

For several years I crewed aboard GIORGIO BOY. Uncle Luigi and I were inseparable and at times, felt like he treated me as the son he lost many years before. My shining moment came when Uncle Luigi got a bad infection in his hand from mending the nets and needed to remain at home for treatment. He announced to the crew that I would skipper the boat for the next couple of weeks.

Unfortunately none of the boats were bringing in any profitable catches so I asked the crew if they would be willing to take the boat off on our own for several days to Farnsworth and Cortez Banks and search for the lost schools. I reasoned that we could lay over at night in Pyramid Cove if the weather churned up. I asked Uncle Luigi if he would allow us to do so. His only condition was that we radio to the fleet if we set on any large schools of fish and that we would keep the catch pursed until any nearby Co-Op boats had a chance to load up.

Call it luck or talent, ego or vanity but when the ISCHIA came alongside to scoop with her huge brail from our bulging purse of sardines (that had to be in excess of a hundred and fifty tons) I felt on top of the world. Brother Dominic would not even say hello, but I could tell by the smile on my father’s face, as he stood on the bridge wing of the ISCHIA, that he was very proud.

During the late 1930’s the government began enforcing the license requirements when going off-shore or to Mexico so I made an appointment to sit for my Engineer and Ocean Operators Licenses along with a Marine Radio Operators endorsement.

My father and mother, Uncle Scagi along with Uncle Luigi and Aunt Anna, decided to return to Italy to encourage the rest of their families to come to America. Everyone tried to talk our folks out of such a perilous journey with war threatening all over Europe, but their minds were made up.

My brother and I became very competitive with our two boats; so much so that we wouldn’t speak for weeks, even though we stayed at our parents house when we weren’t out fishing. He ran for a position on the board of directors at the Co-Op and was elected.

Fish was selling by the canneries and in the markets for ten to twenty times what the boat-owners were being paid for their catches. The cost of fuel went sky-high and most of the fish-boat crews found other employment ashore, in the boat and shipyards, at much higher earnings than the meager portions they were paid on their shares of fish sold at the markets. After all the deductions for food, fuel and maintenance were made, very little was left to support their families and when the catches were small the payoff was nil.

The only muscle the boat-owners and the Co-Op had over the large canneries in Fish Harbor or the group “affectionately” called the forty-thieves at the Fresh Fish Market in San Pedro was to withhold the boats from going out fishing.

THE FISH MARKET

Dominic was in the forefront leading the protest until the government stepped in and twisted the arms of both sides to reach a compromise. Labor unrest in the canning industry was coming to a head and the government thought that a show of militancy on the fisherman’s part would lead further to that unrest.

One side note to this episode was that the government began to scrutinize the residency status of the boat-owners and fishermen, asking embarrassing questions. Many crew members and their families were found to be “not legal residents,” either from not understanding the law or from being lax and not completing the residency or citizenship process.

Because of this investigation a few boats were subject to confiscation under some archaic law stating that boats with foreign ownership that fished in U.S. territorial waters were illegal. An agreement was worked out that the Co-Op would become responsible to operate those boats in question until a final appeal was resolved. GIORGIO BOY was one of the boats in question.

Late in 1941 the attorney handling uncle Luigi’s assets, and now involved in trying to get permission for the family to leave Italy and re-enter the United States, worked out a favorable partial-purchase bare-boat-charter plan to turn the vessel over to the U.S. Army Transportation Service. The Los Angeles built ninety-foot GIORGIO BOY met a criteria needed by the Army to supply military garrisons stationed in the Alaska territory.

The transfer of the boat left me ashore without a berth. Even though I possessed enough credentials, along with ample experience, not many opportunities opened up. Most family owned boats filled top berths within the family and many of the other boats that were operated by the Portuguese, Slovenians or Japanese who insisted that you speak their languages. So, I was forced to sail aboard the ISCHIA for the first time in several years, only this time as the Engineer, taking directions and the usual sarcasm from Dominic….my brother, the Captain.

After Pearl Harbor things went from bad to worse. My parents, uncle Luigi and Aunt Anna were trapped on Ischia. I tried to volunteer in all the military services, if only to prove my families loyalty to America, but I was rejected because my left leg was about half an inch shorter than the right one. The Draft Board interviewers informed me that fishermen had a high draft deferment but I felt I had something more to offer my country than to crew on a leaky old wooden fish boat.

One windy morning while trying to land the ISCHIA at the cannery pier in fish harbor, we maneuvered into the wind trying to get a line to the dock, only to be blown away. The tired old direct reversible, air-injected diesel engine finally had enough and coughed for the last time.

To hear the rantings and ravings coming from my brother, the Captain, you’d think I had pre-arranged this whole episode. The air-compressor was making air as fast as it could but the pressure gauge wasn’t showing any signs of the pressure rising. Unable to find the reason for the engines failure or any immediate solution to get power up, I yelled for him to drop the hook to give us time to study the situation; which he did. The hook grabbed and when the wind swung us around we plowed into a few small boats that were tied up to a pier jutting out into Fish Harbor.

As I explained to the insurance agent, the engine room had no control in the maneuvering of the vessel. A foot pedal on the bridge operated the air injectors for the engine. The bridge controlled the cam reversing mechanism with levers and the bridge also had control of the throttle. In spite of this, my brother blamed me for the entire incident. Even though I owned a good share of the ISCHIA, I never set foot on her again.

The war was putting a crunch on everything; priorities were needed for fuel and engine parts. The Co-Op was able to locate a rebuilt engine after finding that the old diesel had a badly corroded and cracked block. They were waiting for some government agency to give its blessing because of the age and condition of the ISCHIA. They were debating if the vessel was even worth the investment to re-power.

Not willing to just sit idly around waiting for the agency’s decision and having heard that the Army Transport Service needed boat operators, I decided to give them a try.

I hopped a Red P.E. streetcar to Wilmington and hiked down Fries Avenue to the docks and offices of the Port Captain of the Army Transportation Service, Los Angeles Port of Embarkation. I remember that a sergeant was standing behind a long counter passing out applications to several young men in a group and he asked if anyone had any previous sea experience. I was the only one to raise a hand. The sergeant motioned me to come behind the counter and sit on a wooden chair towards the back of the large office area. I had waited there for a good twenty minutes when a man in civilian clothes came out of the office and asked if I was next; he told me to go on in.

The officer sitting behind the desk was reading my application and every once in a while he would look up at me and ask questions, “Just how old are you…eight years, huh…100 Ton License…radio…engineer?”

Then the officer asked, “Think you can pass a physical?”

“I’m in good health…at least I think I am,” I replied.

“Take this envelope to the third floor of the Post Office and Customs Building in San Pedro, then come back here when you’re finished,” said Captain Jonathon Cotton Meyers U.S.A, Director, Civilian Personnel, Transportation Corps. (At least that was what was painted on the plaque on his desk.)

On my return to Capt. Meyer’s office after my physical, I was informed that a tug was going coastwise and asked if I would be willing to sign on as a mate. I agreed and the Captain said that he had a jeep going to the vessel to deliver some papers and that it would be a good time for me to meet the skipper.

The driver had been to the tug before and climbed aboard, with me following close behind. We entered the mess where several men were having a coffee break and the driver asked if the Captain was on board.

“He’s up in the pilot house sorting out all the new charts that just arrived,” said a man with a weather-beaten gold braided “high pressure” hat.

We climbed the ladder to the pilot house. Charts were scattered everywhere and a man was mumbling to himself. When he spotted the young army enlisted driver he shouted, “when in hell are you people going to send me my new mate?”

“Sir, these are your sailing instructions, sign here on this line,” said the driver pointing to a line below a long list of signatures on a large brown envelope, Aand Sir…this is Mister John Di Mello. Captain Meyers sent him over for an interview. I’ll go below and have a cup of coffee.” Then, turning to me, the driver added, “Mister Di Mello I’ll wait to take you back to the office.” He then disappeared down the ladder.

“Well…Mister Di Mello. I’m Captain Tilghman from Seattle. You’ll have to forgive me for staring, you seem so young for a mate’s berth. It says here that you’ve been commercial fishing since you were twelve. You might have more sea time than the most of my crew. I see that you’ve skippered your own ninety-footer for quite some time…Damn good to have you with us!” He said, extending his hand and grasping mine with a firm hand shake, “when can you move aboard? We’re almost ready to sail.”

“If I had transportation I could be aboard by tonight or by tomorrow morning at the latest, if that’s soon enough sir,” I replied.

“Go below and send the driver back up and I’ll see if I can work something out with him. Oh, by the way…your cabin is down the ladder, up forward in the passageway, on the port side.”

On the way back to the Port Captains office the driver indicated that he would try to get permission from Capt. Meyer to help me get my gear aboard the ship that night.

The Government can move fast if it really wants to. What followed was a long full day of signing contracts, insurance forms, personal character information releases, interviews…. etc, after having doctors poking me and taking blood and urine samples earlier that day.

By nine o’clock that night I was delivered on the dock with all my personal belongings. In one suitcase there were navigation books, pictures and papers. A large satchel-style case held a few changes of clothing; anything else left behind I could do without.

A crewman met me on the dock and helped me aboard with my gear. He informed me that the Captain wanted me to report to his cabin the moment I came aboard, no mater what time it was.

I climbed up to the pilot house and knocked on the door of the Captain’s cabin and a sleepy voice bellowed out, “Who is it?”

“It’s your new mate Johnny Di Mello, I was told to report to you when I came aboard, no mater what time it was,” I responded.

“I’ll be with you in a minute. In the meantime bring your gear to the bridge and move into that cabin on the port side. There’s been some temporary changes,” said Captain Tilghman.

I went below to get my baggage and struggled with getting all my gear up the narrow ladder to the bridge. When I opened the door to my new cabin I saw a radio panel and chair taking up the whole inboard bulkhead, with a bunk on the outboard side and two portholes, a sink and a clothes locker aft. It was an improvement over the other cabin, down below, that I was to have shared with another mate.

Captain Tilghman knocked and entered the cabin. “I noticed that you had a radio operator’s license listed on you qualifications. That and the fact that you’ve held certain other responsibilities have made me decide to sail with only three watch officers instead of taking on another untried mate that I’m not familiar with. It means that I’ll have to stand a watch, you’ll have navigation and radio and my other mate will have the deck. It wasn’t planned this way but we were running too short on time for getting under way.”

“Thank you sir, I can only hope I don’t disappoint you,” I said, trying to hide my pride and excitement. “When are we to get underway?”

“Sea watches will start at midnight. We’ll go to the outer harbor and pick up our string of tows by eight in the morning. From your dossier I see you’ve sailed up and down this coast, so you’ll be plotting us a course north….here are the radio frequencies and schedules of when you’re to monitor…have you met the third yet?” The captain handed me a sheaf of papers with a lot of government jargon only they could possibly decipher.

“If that was the gentleman I was to share a cabin with, not yet. He was sleeping sound as a rock,” I replied.

“He’s a good man with a lot of sea time, sailed as A.B. and Bo’s’n on tugs in the Sound for years. He doesn’t want to navigate, but he is a damn good deck boss….and doesn’t mind sailing as third. You’d better turn in….I’ll see you in the morning.” With that the Captain returned to his cabin and I went below to raid the night watch snacks before turning in.

The start of what sounded like a pump hammering, deep in the bowels of the ship, broke the night’s silence. I dressed and made my way down to the mess. The cook and a man that I took to be an Engineer were the only ones stirring so I grabbed a cup of coffee and sat with the two men.

“I’m First Engineer, Tom Rudder, and this is Cookie…say what is you’re real name Cookie…I don’t ever recall hearing it?” Rudder thrust out a hand that he just wiped clean with a hand full of waste that was in a bundle made up from long strings of assorted cotton threads and yarns.

I shook the engineer’s hand and waited for the cook to wipe his hands clean on his apron that showed signs of flour and dough particles from bread making.

“My name’s Gianni Di Mello,” I said, Abut I’ll answer to Johnny, glad to meet you two. I guess I’m the new mate, unless things have changed again since last night….” I started to reach for a sweet roll on a plate when “Cookie” stopped me saying that some cinnamon buns should be just about ready and headed towards the galley.

The mess started crowding up with crewmen. They all introduced themselves, giving their first and last names and always following up with some nickname.

An older bearded fellow came in from out on deck and hung his high-pressure cap on a coat hook by the doorway and started for the coffee urn. I immediately took him for the third mate and went to introduce myself, “You must be the other mate, I’m Gianni Di Mello.” I held out my hand, but I got nothing in return.

“I had no idea that you were just a kid…what…did you just graduate from some school?” He growled as he poured his coffee.

Everyone in the mess froze in their seats waiting for my response. “If you are the other mate then I suggest we go to the pilot house to discuss this further. If you’re not then I suggest you go about your own damn business,” I said, looking him squarely in the eyes. I turned and started up the stairwell with the old fellow following right behind.

Unbeknownst to me Captain Tilghman had arisen earlier, gone below to get his coffee and came back to his cabin to read his sailing instructions. While getting his coffee he ran into the old mate and informed him that the ship had finally got a mate with good navigating and sea experience….but failed to mention my age.

As we approached the helm area, Captain Tilghman came out of his cabin and said, “Good morning gentlemen…I was just about to send for the two of you. I wanted to introduce you….we have a lot to plan before we get underway”.

“Sir if you will allow me just one moment with the mate here?” I turned to the old fellow, “Don’t you ever dress me down in front of the men again. If you have anything to debate or question concerning me, call me aside and I’ll discuss it with you…is that clear?”

Captain Tilghman interrupted, “Hold on gentlemen, I might have made a mistake by not introducing you two last night but I thought we would have had time to do it this morning. Let’s go into my cabin and discuss this further.”

The cabin had a two-seat green leather bench, a desk attached to the bulkhead and a chair. The bunk, locker and sink were aft. We seated ourselves while the Captain sorted out some papers then handed me a copy of my application. “Would you mind if Andy reads this? It may answer a lot of questions for everyone.”

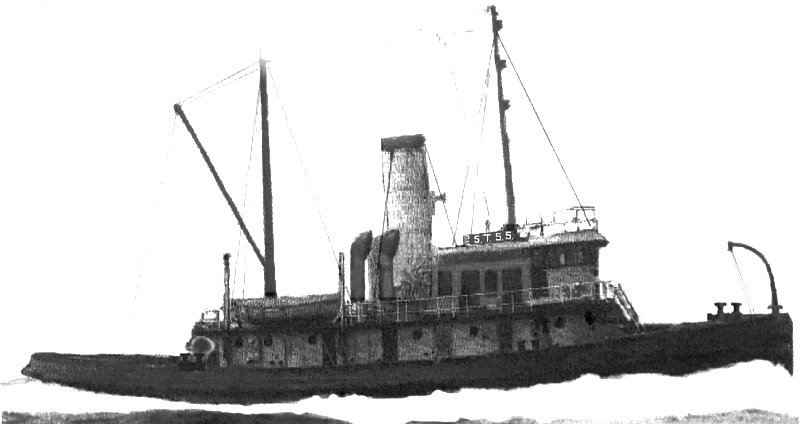

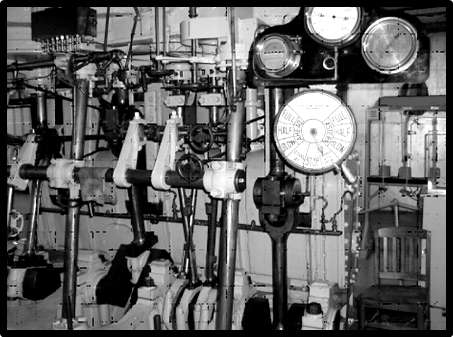

S.T. 55

A powerful long distance tug, at 118 feet and powered by a 1,100 IHP reciprocating triple-expansion engine with two water-tube boilers and a small donkey-boiler for a stand-by power plant.

“Not at all Captain,” I said as I handed the document to the old mate. While he was reading it Captain Tilghman handed me several sheets of the tug’s dimensions and capacities, including cruising ranges and speeds. When I was first informed about signing aboard an S.T. I envisioned a small 65′ to 75′ (Small Tug) like I had seen working the LA harbor. I was surprised to find out that the ST 55 was designated as a (Steam Tug). She was a large old steam tug built in New York after the first war for the Panama Canal Company, then later turned over to the Army Corps of Engineers. She now belonged to the Army Transport Service and was in-route to be re-assigned to the West Coast (after working the Chesapeake for many years).

On her way to the West Coast she brought two 155 foot steel BCL’s, barges with covered deck houses, from Charleston, South Carolina which were now waiting for us in outer harbor.

Seeing that the mate had finished reading the document, the Captain took it and put it in his bulging briefcase.

“Now I suggest we go down to breakfast and I’ll introduce you around,” said the Captain as he ushered us out of his cabin.

“Sir, if you don’t mind I’d like to introduce Mister Di Mello…I sort of…owe him an apology.” Then turning to me he asked, “only…If that’s alright with you Johnny?” offering his hand, I took it and we all went down to breakfast.

As we wound our way out from the back channels and into the outer harbor I kept an eye peeled for any fish boats I might recognize. A cold damp morning mist hung about, just enough to wet the decks and require a warm jacket. I had made this trip maybe a thousand times since I was a kid and everything today was reminiscent of being back on the GIORGIO BOY.

Captain Tilghman spotted the two barges with their pinched bows out near the breakwater with two harbor tugs standing by. We pulled alongside the forward barge and the old mate, Andy, jumped aboard with a few deck-hands to check the bridle. He then went aft and inspected that towing gear. Captain Tilghman had control of the tug from a station on the after boat deck. We maneuvered our stern around and sent a messenger line to the three men on the barge who tied the line to the large bridle shackle. We winched the whole assembly aboard our stern and attached our two-and-a-quarter-inch diameter towing wire. With everything ready, our crew returned to the ship and we were ready to sail.

The two tugs assisted us out through the submarine nets and as we left Angel’s Gate behind we slowly payed out our wire and gained speed. The two small tugs fell astern and returned inside the harbor.

I remained in the pilot house all that first day and well into the night. Captain Tilghman suggested that I stand by as we approached the gap between the Channel Islands and the mainland, because of my local knowledge. It also gave me an opportunity to learn many interesting things about the ST 55.

While waiting clearance at Balboa in the Canal Zone, the original first mate had gone ashore and failed to return. The Captain had to stand watches until the ship arrived in Los Angeles. He said he interviewed three applicants and was not impressed with any of them. I half jokingly asked if he only took me because time was growing short but he assured me that wasn’t the case.

We had fourteen men in the crew: The Captain, two deck officers and three deck-hands (able bodied seamen) comprised the deck crew. A mate and AB stood a watch together, relieving each other on the wheel and at lookout. The Engine crew had three engineers and three F/W’s (firemen/water-tenders), with an engineer and a F/W standing watches together. Then there was the cook and a mess utility man. Once the routine of sea watches took hold everything ran smoothly.

Captain Tilghman kept the pilot house alive with all his sea stories about the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. He was surprised that I was also familiar with many of the Alaska Gulf ports that he mentioned. I told him that many Southern California fishermen made annual trips north when the Sardine season evaporated and that a few of them stayed on at Kodiak to establish their own canning and commercial fishing stations.

Most of the men now on board were sent to the East Coast from Seattle to return aboard the ST 55 as her delivery crew. The crew knew the Captain’s stories by heart as many of the crew had sailed with him before this assignment. He was good-natured about the crew prodding him to retell some episodes even when they corrected him when he left something out.

Andy, the Third Mate, also had a few yarns to tell and we became good friends. He introduced me to the towing engine and all its many functions. Though a bit more complicated and steam driven, it was similar to some of the new wire-drum winches on the fish boats.

He also demonstrated how important it was to maintain a distance relationship between the tows and our ship. If the swell pattern is constant you can ease the wire until the tow and the tug were in somewhat the same rise and fall mode, thus relieving the strain on the bridle and wire. He also taught me that it was better to have a lot of wire out, as the weight of the wire helped to drag the tows and allowed for less strain on the winch or ship as the towing wire stretched or eased.

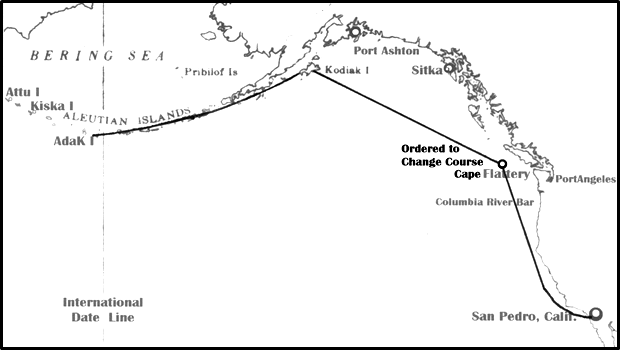

Our final destination was Port Ashton near Seward, Alaska. The Captain had the option to continue on to Sitka, without making an entry around Cape Flattery and into Port Townsend, our first destination, if a need arose.

The weather cooperated and the sea was comfortable with long shallow troughs between the swells as we continued north past San Francisco and the Columbia River. The barometer lowered slightly and a chill filled the air, though no reports of inclement weather were reported for our area. Our bunker fuel reserves were excellent, the cook had no shortages and the machinery was operating like a fine-tuned watch.

We were averaging a little over six knots, after eight days and twelve hundred miles out of Los Angeles and almost two hundred miles beyond Cape Flattery, things rapidly began to change. The weather started veering around from the normal Northwest to a more westerly direction and then the wind really picked up. The swells were still coming from the Northwest but a cross-chop was developing because of the westerly winds and was beginning to play havoc with the tows. The after barge seemed to be drifting way off to leeward and began to yaw. Her gyrations were causing the forward barge to drift with her.

We slowed to a crawl with just enough headway into the weather and started reeling in the wire. All hands were rousted while the Captain searched for what must have been a problem with the bridle. It appeared that the starboard chain lead was hanging down and limp. The port side lead was all that kept the barge under tow and caused the barge to drift off to leeward.

The Captain decided to launch the motor lifeboat with a crew that included Andy, an AB, Engineer and a fireman. They loaded the lifeboat with heavy block and tackle, shackles, wire clamps, tools and an assortment of lines for any and every possible need. The cook filled a pillow case with sandwiches and several half-gallon cans of apple juice.

The lifeboat was swung out, her engine was tested and it started right up. We maneuvered around until we found a direction with the sea and stiff breeze that afforded the safest launch. The lifeboat was released from the falls without any problems and she was on her way.

Andy and his crew boarded the after barge and began to pull up the slack starboard bridle chain lead. From the amount they hauled aboard it must have parted at the lead shackle and that meant that they would have to haul aboard the whole bridle….plus a portion of the towing wire.

Captain Tilghman maneuvered our tug directly into the breeze, then stopped the engine to allow our tug and the first barge to drift towards the second barge so as not to permit the towing wire to draw taught. It was a slow procedure. They could only hook about four or five links of the bridle chain in each block and tackle hoist and transfer that to a stopper, then start the whole process all over again.

An AB hung a gunny sack over the side of our ship with an oil container in it to help smooth the seas. Every once in a while we could see the towing wire almost straighten out between the two barges and we could see the men secure the tackle to the bitts until the wire went slack again. With a lot of hard effort the problem was corrected and the crew started tossing the tools and lines back in the lifeboat for their return to the ship.

It was late afternoon and the breeze was increasing to twenty plus knots when we noticed that the lifeboat wasn’t making any headway. Andy was standing on top of the engine housing waving his arms wildly above his head.

I grabbed for the signal lamp and blinked, asking if they were in trouble. Andy raised his right arm indicating yes. We could see him point towards the engine and make a motion as if he was cutting his throat, as they drifted further and further down wind.

Captain Tilghman took the helm and ordered me to keep them in sight at all times. I signaled to them again with the blinker light that we were going to begin a big sweeping circle.

The lifeboat soon became only a dot. I lost them several times and my heart came up in my throat each time. The sun was on the horizon and we had only a few minutes more to plan our approach and retrieve them. I had to go to the other side of the pilot house to keep them in view. I scanned an area with the binoculars where I thought the lifeboat should be, but I couldn’t find them. I panicked and called out to the Captain that I lost them.

We were now heading towards the last rays where the sun had just set below the horizon and into a now lessening wind.

“Don’t lose your control son, I’m sure we’re in the right spot. They should be just off to starboard…keep a sharp lookout”. The Captain’s words were supposed to be comforting, but did little to ease the guilt I felt for losing sight of the men.

All hands were topside searching. We were making less than one knot, just enough to maintain headway with the string of barges strung off behind us. The Captain was now on the starboard bridge wing, an AB had the wheel and I was on the port wing.

“I see a light dead ahead…It’s them!” I cried out. “They’re about a mile out and just off to starboard!” I can’t think of another time in my life that I had prayed with as much contrition as I had that day after losing sight of the lifeboat and the men in her.

The Captain went to the after boat deck control station while the AB and I went down on deck to help retrieve the lifeboat.

The falls were hooked and the lifeboat was hoisted and nestled in her chocks. All the gear was off-loaded and stowed. Then everyone went below to the mess to hear another real-life tale as only Andy could tell it. He kept us hanging on for every minute detail….even though most of us had just lived through every second with him.

Eight o’clock; it was time to be relieved by the Captain. I told him that I had a few calculations to work out and that it was almost our scheduled time to monitor our radio frequency.

I fired up the radio on the hour and was amazed at all the traffic. It sounded as if every ship at sea was being paged and that advisories were out for almost every area out west.

Our monitoring time came at ten minutes past the hours of 12-4-8 around the clock. The radiomen along our route normally spoke in a dull monotone without any emotion but tonight two, and at times three, announcers were stomping on top of each other, calling out for all vessels west of 1581 west Longitude and north of 0541 north Latitude be advised that condition four was now in effect. It was almost impossible to distinguish what Morris code transmission belonged to what string without extreme fine tuning.

Calls were made for so many ships. For example: “FOX PETER SIX-FIVE” or “TARE FOUR-SEVEN” were called out with trailers such as “REPORT NOW”. A weather report for Anchorage and our immediate area didn’t seem very critical. My eavesdropping concentration was broken when I heard, “SUGAR TARE FIVE-FIVE… SUGAR TARE FIVE-FIVE”. I waited for a few moments expecting further instructions when I remembered that I had to switch over to another frequency that was on a separate crystal. I waited, listening to all sorts of complicated jargon when our call letters were called out and then a trailer “EXECUTE ALTERNATE ORDER 11-152 CHARLIE…I REPEAT”…which he did and with the following trailer, “CONFIRM!”

I called out for the Captain to come quick and he charged into the radio shack wanting to know what was so urgent. I handed him a copy of what I was able to make of the transmission. He studied the page while keeping an ear peeled to the radio traffic.

“What in hell is happening? Listen to that,” he said as another announcer broke in with additional warnings of all ships within certain areas to find shelter. “Sounds like all hell is breaking loose!” He exclaimed as he headed for the chart table in the wheelhouse.

The third mate came into the radio shack and listened for awhile. He couldn’t understand what was happening and asked, AIs it a storm or are the Japanese over-running the area?”

Captain Tilghman returned to the shack and laid out the sailing instructions. “Our initial port-of-call, according to schedule (A-Able) 11-152, was to be Port Townsend but it was left to my discretion whether or not to continue on if everything, including the weather, was normal. (B-Baker) is Sitka, (C-Charlie) is Kodiak, with Port Ashton (D-Dog) being our primary destination. We’ll have to plot a course to Kodiak. Do you have any problem with that Johnny?”

“No sir…unless…the weather kicks back up…It’s on a more westerly heading so maybe we better study it a bit more closely before we report in and confirm.”

Captain Tilghman ordered the steam valve opened to the maze of tubing heating coils which were attached to the pilot house forward bulkhead. The drains were opened and water streamed out until steam began to blow through the cock, and they were then closed. The outside temperature must have dropped thirty degrees in the hour since the sun went down.

We held our new course for a short while and, finding it acceptable, I keyed confirmation of receiving our new orders. We settled back into our normal routine, only this time the Captain wanted the radio turned up so the bridge could monitor all the transmissions, especially to find out if they received our confirmation to their new orders. I turned in and tried to sleep even though the radio was blaring away in my ear.

I don’t know if it was the radio blaring, the motion of the ship, or it could have been a dream but I thought I heard “SUGAR TARE FIVE-FIVE” called again, with a tag “TRANSMISSION CONFIRMED”. I got up and went into the darkened pilot house and asked if anyone heard the radio calling us. The mate and helmsman said that they weren’t paying any attention to the radio because they had all they could handle steering in the rough sea. And, with the wind blowing, it sort of drowned out the radio, especially after the captain turned it down so he could get some sleep.

It was 0300 and almost time for me to get called for watch so I decided to get up, dress and go below for some coffee and sandwiches. The only person around was the fireman on watch who was grabbing a pitcher of coffee to take below to the engine room.

“How’s it going down below?” I asked just to strike up a conversation.

“No real problems, we’re running low on condensate since the evaporator started brining up and won’t descale. Besides that, everything else is running great. How’s the storm? Getting any worse out?”

“To hear the radio you’d think it was a raging hurricane but it’s staying well out in the Bearing Sea and the Outer Aleutians. I guess it could come this way but we should make port before we get the brunt of it,” I offered, knowing that anything I said would get passed around and I didn’t think it necessary to start any rumors of any possible danger.

I relieved the third at 0400 and turned up the radio just enough to monitor it on the bridge. I noticed that the engine revs were down to 60 RPM’s and we were still taking blue water over the quartering bows. My first thought was of the tows and how they were taking these heavy seas. I asked my AB to keep an extra sharp lookout while I went aft on the boat deck to see if I could make out how the barges were doing.

When I went out on the after boat deck I hadn’t realized how cold it was and I had to return to the bridge to get a foul weather suit on. When I went out again I couldn’t see the tows but the wire was strung out tight as a bow string. After I returned to the bridge I blew into the voice tube to raise the engine room. I instructed them to reduce the engine revs to 50 turns. I also ordered my AB to slowly steer a little more off the coming sea. As he brought the bow around to where I thought it was a good approach to the swells I asked for his compass heading and told him that it was now his new course.

As a hint of daylight came around; the outline of the swells could barely be made out. From the outside railing of the pilot house the faint outline of the barges proved that they were still with us. The traffic on the radio was still hot and heavy. I was eagerly looking forward to a warm bunk. Sleep was the only thing I craved now. Not food or drink. Just sleep. But I still had to monitor our frequency at ten past eight.

Captain Tilghman came on the bridge twenty minutes early and relieved me so I could go below and have breakfast. I gobbled down the toast, coffee hot oatmeal drowning in a sea of watered down dried milk and then went back to the radio panel. Being a few minutes early I switched to see what kind of chatter was on the other frequencies.

I happened on one frequency that was warning planes in areas of certain (coded) fields, that those areas were closed due to fog, high winds or heavy rains. Every frequency had some kind of emergency-type warnings.

Five minutes after eight I logged on to our frequency and began listening to all the emergency traffic. Full gale warnings were issued for vessels west of 1481 Longitude and north of 0541 Latitude, which now included us, and we were still two hundred miles from our destination, doing less than three knots, trying to reduce the strain on the two barge bridles after our experience of yesterday afternoon.

Around eleven hundred hours I was awakened from a sound sleep and thrown against the outboard bulkhead side of my bunk. I tried to pull myself to the inboard edge so I could climb out but the ship just stayed in that heeling position and it took all the muscle I had to pull myself up and out of the bunk. I put on my trousers and slippers and went into the pilot house.

To my surprise no one was at the helm….in fact there was nobody in the house at all. I started out the leeward wing door which was also the down side of the heeling ship. I quickly closed the door when I found that a full gale was blowing outside and freezing cold.

I went out on deck and saw the Captain at the after steering station then I returned to the pilothouse. I called down to the mess but nobody answered. I quickly got dressed in all my foul-weather gear and headed aft to where the skipper was, screaming as loud as I could, hoping to be heard over the gale-force winds. “Why are we heeling so bad…will she come out of it?”

“We were in the process of bringing the ship around…. planning to go down-wind to relieve the effort on the towing wire….we got broad-sided in a trough…heeled over and somehow the wire broke loose from the preventer-chain and got caught ahead of the aft quarter bitts on the rail when we rolled….the tows now are almost dragging us sideways,” shouted the skipper. Then he added, “if we try to steer ahead….we’ll only lock the wire to the side of the ship…go see if you can help the mate….he’s on the deck below.”

The leeward deck was awash. Most of the crew were huddled in the towing engine compartment while the old mate and an AB rigged up a heavy steel snatch-block out on the fantail with a wire reeved from the capstan through the block and back to the towing wire. All this was being done with the men crawling on all fours while the freezing sea surged all about them. Had the towing wire released itself and lashed around to the fantail it would have done so with enough force to decapitate both of them.

Several attempts were made to start the capstan while the wire was wound on the drum with a man tailing, but the reaction time was too slow. As the ship rolled the towing wire would rise off the rail for only for a brief second or two and then lay back down in the captive position ahead of the large bits on the rail.

An old fish boat trick came to mind. “Open the steam throttle valve for the capstan as wide as you can and let the barrel spin free…put a couple more wraps of wire on the barrel and let the wire ride free…here let me tail.” I grabbed the wire, the capstan head was turning fast, the ship started to roll and as the wire lifted off the rail I pulled on the monkey’s tail and the small wire stretched from the snatch-block to the towing wire and hauled the large wire aft and clear of the bitts. After we cleared the problem it suddenly occurred to me how lucky we were that the snatch-block held instead of breaking loose and slamming into all of us that were gathered within its bight.

Clearing one hurdle was fine but we had several more to clear before we were out of trouble. The matter of going down wind and away from our destination to ease the strain on the tows meant that we were eventually going to have to make up all that lost time and distance before our condensate ran out, because the evaporator’s problems came to light well after we cleared the Washington coast and was now unable to make any fresh water for the boilers.

The Captain suggested that we rethink our progress. We tried every possible combination of easing the strain on the tows. We went up wind, down wind, every angle and at every speed. The only combination that we agreed was best was to resume our normal course, heading towards our destination and at a much slower speed against a fifty knot gale.

Almost three days later we made land fall at Cape Chiniak, rounded Woody Island and anchored in Kodiak at nightfall. The storm was still playing havoc outside but the calm waters in the island’s shelter gave us one good night’s rest before our unexpected next assignment arrived the following morning.

At 0800 the next morning a launch was plowing its way through the wind and chop towards us. She blew her horn as if trying to get our attention as she came alongside. One of our AB’s took a line tossed by the launch’s deck hand. Two army officers climbed aboard our ship and were directed to the mess.

Captain Tilghman introduced the ship’s officers who had remained in the mess after a ship’s deficiency meeting. An army Major was the senior officer and after a brief over-view of our voyage he congratulated us on our difficult trip and said that we should work up a ship’s replenishment list and present it to him before he left the ship.

Captain Tilghman invited the army officers to the bridge and asked me to bring up a pot of coffee and cups. When I arrived later, I filled the cups and passed them around. The Captain announced to me in a most unusual manner and tone, “These officers want us to prepare the ship for getting underway immediately.”

“But sir….we have several problems that need to be attended to….sir,” I replied.

“Like what?” The Major asked.

“For one thing we have no condensate and no evaporator to make condensate,” I answered. “Also, we need bunkering…we’re running low on perishable stores and…. don’t forget that we’re still hooked up to the tows. Give me some time and I’m sure I can find several other needs.”

“And just what was your position aboard this ship?” The officer asked again.

“This young fellow is my Chief Mate and what he says is the truth. We’ve about exhausted everything, including the crew, on this voyage,” replied Captain Tilghman, and added “We’d be glad to sail if we could get the supplies. Our boilers have to have good fresh water; unless treated properly, anything less will damage the boiler tubes. Our fuel supply is down to less than a two hundred mile run….by the way Johnny, the equipment in the barges is needed by the Army Air Corps….now. Call down and have the Chief Engineer sent up.”

After calling down for the Chief I returned to the Captain’s cabin. During a lull in the conversation I mentioned the need for charts and sailing directions for the area, especially if we were to be going further out in the islands.

The Chief Engineer arrived at the Captain’s door, coveralls wringing wet with sweat. He was a crusty old Irisher and his bulbous red nose and rosy cheeks told a history of battling the bottle at some time in his life. If he did have a few bottles hidden aboard now, nobody knew or wanted to know of it, as he was a hard working man and knew his boilers and the large reciprocating steam engine like the back of his hand.

“Sorry about being late but I was inside the evaporator trying to chip out the salt build-up. I also found a hole in one of the coils. We might be able to save her if we had a day or two,” apologized the Chief.

“Chief, the Army wants us to get underway immediately. When can you crank her up?” Captain Tilghman asked.

Similar to S. T. 55’s Triple Expansion Steam Engine

The old Chief scratched the white stubble on his chin. “We could leave right now but they would have to come and tow us back in sometime tonight, we’re starving that bad sir.”

“Who can supply this….condensate water that you say you need Chief?” The Major inquired.

“Most any steam ship sir, if they be willing to part with it. There’s a Liberty and a Hog Islander at anchor. If we could persuade them of our need…maybe….Is the Army on good terms with any of those ships in the harbor?” Asked Captain Tilghman of the Major and then turning to the Chief he asked, “and there’s also the problem of fuel. How much and what kind do you need?”

“Let the army answer your first question sir,” said the Chief looking at the army officer. “As for fuel we could use anything except wood or coal.”

I wish you could use coal because we’ve got tons of it piled all over the island,” said the Major. “As for that liberty ship, she’s under army charter waiting to go dockside to off-load. I’ll go over now and talk to her skipper. I didn’t realize your ship was in all this need. If I can you get the water and fuel, when can you get underway?”

Everyone looked at the Chief, waiting for his reply. “If I had a couple of extra mechanics and a welder so I didn’t have to break sea watches we could be ready by late tomorrow or the day after, no later. My crew can’t work steaming watches and work extra hours on top of that. I personally don’t mind doing it cause that’s what they expect of a Chief….ain’t that right Cap’n?”

“Right Chief, you can go back to work now and on your way down be so kind as to send up the cook.” Captain Tilghman had a way about him that put you at ease in his presence while maintaining his authority and dignity and was very gracious in his manners.

“You sent for me skipper,” asked the cook.

“What are your primary needs Cookie?”

“I have the list here sir; Fresh meat, milk, eggs, fresh fruit, vegetables….the cook wasn’t able to continue for all the laughing from the two army officers.

“We’ve been here three months and have seen hardly any of that stuff since we landed here. America doesn’t even know we exist! Half the people don’t even know where Alaska is or who it belongs to. The Japanese are on American soil at Attu and Kiska Islands and no one seems to care.” The young Lieutenant started to say more but the Major held his hand up and the junior officer fell silent.

“Captain Tilghman, maybe you should get a list from the army of what they do have and I’ll select from that.” The cook turned on his heel and exited.

“Captain Tilghman…Mister Di Mello. What I’m going to tell you should be kept between us only. The recent storms have left the landing strips out in the western archipelago a disaster and all the heavy equipment is buried deep in the mud. Planes can’t take off or land and there’s no machinery available to dig out the buried equipment to repair the strips, with the exception of what you are towing in your barges. Anchorage says they need this road machinery. Our Aleutian Command says if we aren’t able to stop the Japanese in the islands, nobody left in this theater will ever again need roads.”

“We had no idea…the army can count on us, they’ll have our fullest cooperation.”

“Of course you can count on us Major…but…how will the scrapers and dozers be off-loaded? Are there cranes out there?” I asked.

“We’ve already battled with that question. You’re going to take a few army welders with you and when you arrive a couple of small ‘T’ boats, at high tide, will push the barges broad-side-to on the beach and the burners will blow a large hole in the side of the barge and then drive the machinery off,” explained the Major.

“Jesus…is it that bad?” I asked.

“It is that bad,” replied the army Major as he stood to leave the cabin. “We’ve got a lot to do and we better get cracking.” The two army officers departed the ship.

Two hours later a half-submerged wooden barge with a huge tank on its deck was brought along side by a small old wooden tug. Her skipper said he had an order to deliver fuel to us and he began rigging the hose boom.

The Chief Engineer took a sample from the barge’s tank and went below to the engine room to test the fluid. He returned on deck and ordered the pumping to begin.

A trawler-like work boat pulled along the opposite side and tied up. A Warrant Officer came aboard and asked to see the skipper then a short while later the Chief Engineer and the Third Mate were called topside. I was in my cabin monitoring the radio and sorting out charts that had just arrived and overheard their conversation about berthing four new men and what their duties aboard ship would be. It seemed that the engine room was to use their services for the trip, as they were going to repair the evaporator coils also. These were the men that would burn open the side of the barges to off-load the equipment.

It was apparent from all the activity around our ship that this was serious business. Launches were coming and going all afternoon delivering stores. On one occasion I heard a man call out in Italian to another; a loose translation was, “These idiots are crazy to sail in this weather!” The other replied, “They sure do feed good on this ship. Look…fresh meat!”

“If you guys worked as hard as we do they might feed you as good,” I replied in Napolidon, thinking I caught a hint of that dialect as opposed to the heavy gruff-like Siciliano.

“Hey, Compadre!” One shouted. Then they both began to rattle off questions; asking where I was from and did I know this family or that family. I soon found out that they were shirt-tail relatives of the Di Mellos and that a large family of Iaconos also lived on Kodiak.

Our get-together was short-lived for they had other deliveries to make to other ships. I told them the men on this ship had never tasted good cioppino and offered to buy some fresh Salmon or Halibut. They said they’d try to come back with the fish and maybe some King Crab legs.

Our boiler condensate arrived the next morning. I had to go ashore to confirm some discrepancies on the charts and get the latest radio frequencies. I saw my Italian compadres and wrangled a ride back out to the ship. They were on their way to deliver about thirty-five pounds of fresh, assorted, and dressed fish and crab legs….all for just a few bucks. What a bargain! We had a lot of good old home conversation on our trip out to my ship.

That afternoon I persuaded the cook to let me help fix dinner. I told him I needed salt, pepper, garlic, oregano, parsley, onion, cayenne, tomatoes, olive oil (extra virgin preferred), a couple of pinches of sugar…. and red wine, if available.

The cook baked several loaves of sourdough bread while my sauce was simmering and the aroma of garlic and seasonings was driving everyone wild.

Preparing cioppino is a ritualistic procedure practiced for generations by most Italian fishing families. Originally a common dish, it was prepared with the left-over fish and shell fish that didn’t interest the fish buyers. These assorted remnants were thrown into the ever-present marinara sauce and usually served over pasta.

Each family prided themselves on their own cioppino recipe. Something was added by one family or cooked slightly different from the next family, until, in some areas, it became a contest and judges were appointed to select the best of the best. Every year Aunt Anna entered our local contest and was always one of the top two or three finishers, and won many times outright. The cook-off was a fine excuse for the families to get together and gorge themselves on cioppino and good Dago Red!!

Aunt Anna’s secret was in presenting the fish into the sauce at just the right moment; never over-cooking the fish. Her sauce was of just the right consistency to be sopped up with large chunks of sourdough bread.

As I was serving the meal to the men I told them of all the nuances of Italian cooking, from the wine preferences to the bread and cheese selections. And just before they were to begin eating I prevailed on them to let me demonstrate the proper way to enjoy cioppino by tearing off a piece of bread and soaking it in the sauce, then with both hands I dug into the sauce and fished out a crab leg and cracked it and slurped the meat out with a deep sucking sound as the red sauce driveled down my wrist to my elbows. “Now that’s the way to enjoy cioppino!” I announced.

Early the next morning, Third Mate Andy and I made a hands-on and visual inspection of all the bridle links and towing assemblies. All shackles, pins and clamps were tightened and wire-seized, to prevent them from backing out. Since Andy was more familiar with this end of tug-boating I left the decision of their safety up to him.

The evaporator was desalted and the coils were silver solder patched and pressure tested. After a time, the evaporator was put on-line and began making water. We were ready to depart the shelter of Kodiak for an island called Adak, nearly one thousand miles to the west.

The wind was brisk at twenty knots, with gusts up to thirty. The swells were coming out of the southwest with about a five foot trough. We were riding comfortably except for the occasional large sea stopping us in our wake. Still, five knots in these conditions was not bad.

The army G.I.’ s thought they were in a living hell. They were so seasick that they couldn’t eat or go below to the fo’cs’le for several days and seemed to only find comfort in the after winch compartment. In fact, they set up cots and camped there for the remainder of the trip and eventually did overcome their mal de mer enough to visit us at the mess.

Finally the seas calmed and we were frequently logging up to seven knots as we passed close to nearby islands. On the seventh day we entered the channel at Adak.

A navy patrol craft challenged us for identification by blinker light, ordering us to lay-to until other vessels were sent to assist us. A couple of LCM’s and LCVP’s came along side and said that they were going to take our tows and that we should stand by to unhook from the tows.

An officer’s gig came along side and a Navy Lieutenant came aboard and was escorted to the pilot house. He informed Captain Tilghman that a large attack transport had arrived and that they had a heavy lift boom and would off-load the road equipment from our barges to the LCM’s to save from destroying the good steel barges.

The Navy had agreed to cooperate with the Army in their plight at the air strip on Amchitka, which was less than two hundred miles further west and only seventy miles from Japanese-held Kiska. Since there was no deep water shelter or piers at Amchitka, most everything had to be taken ashore by landing craft, or barges that were shoved ashore.

As for the big beautiful steel barges, the Army Air Corps needed weather-protected engine repair work shops, and they thought that our barges were the perfect answer to their needs. It was indicated that when they no longer needed the road working equipment they would put the stuff back aboard the barges and tow them to Anchorage.

We were glad to be rid of the burdens our ship had towed for nearly eight thousand miles.

We were ordered to proceed to Dutch Harbor and assist a cargo ship under an Army charter to Kodiak. The only information the Navy had was that the ship was vibrating badly and her skipper didn’t want to sail without an escort.

The trip to Dutch Harbor was uneventful as was the escorting of the cargo ship to Kodiak.

Fall weather was fast approaching and many waterborne activities in the outer Aleutian Islands, Bristol Bay and points north were put on a temporary operational hiatus due to a constant string of incoming low pressure systems. We refueled and were ordered to Anchorage.

On our arrival at Anchorage I was admitted to the hospital with a high fever. I was diagnosed as having an appendicitis attack. After a successful surgery, transportation was provided to an army hospital near Seattle.

While recovering I was offered a position to teach a class of newly hired prospects in seamanship and small boat handling at the army port facilities at Bellingham, Washington.

The Army had recently sent several flotillas of T-boats, along with other small craft, north and had a very poor destination arrival rate, either from lack of basic seamanship skills or deliberate damage to keep from having to continue on into uncertain waters or fearful of rapid weather changes. Several crew members had abandoned their vessels, leaving those vessels too short handed to continue their voyages.

After interviewing several crewmen it was determined that some of the vessels were very unstable due to the lack of proper cargo stowage and ballasting.

In early Spring of ‘44, a large flotilla left Bellingham for the trek north through the Inside Passage. In the original group of 12 assorted small craft, with close to a hundred seamen, every vessel arrived at their destination….Along with two additional small craft that had been abandoned the previous year.

A sad footnote to this tale is the disappearance of the ST 55. When I inquired about the ST 55 no reason was offered for her disappearance, but what is so mysterious is that no official record of the vessel or her crew is to be found anywhere…It’s like she never existed…

In the late 1940’s my mother and father along with Uncles Scagi, Luigi and Aunt Anna returned to San Pedro. Brother Dominic and I patched our differences. He married and started a family. The clan returned to the commercial fishing industry. I liked sailing on merchant ships and recently sat for my Master’s license.