- HOME

- ABOUT

- PERSONAL STORIES

- CAJUN

- LAS FLORES

- MIGHTY ONE

- WHARF RAT

- YALE STREET ICE HOUSE

- CAPTAIN CHAS. NOBLE

- A MIKI-MIKI TUG

- TAR-BABY

- NORTH ATLANTIC CONVOY

- OPERATION MULBERRY

- PEASOUP ON A POTATO PATCH

- S.S. CANBERRA’S FINEST HOUR

- ISCHIA

- THE F BOATS

- OCEAN LIGHTER

- ZAMBOANGA MONKEY CAPER

- TURMOIL ON TAWI-TAWI

- PIER-HEAD JUMP

- REQUIEM FOR A FRIEND

- FITCH THE BITCH

- WATER TAXI

- TALL TALES

- GALLERY

- GRATITUDE

- CONTACT

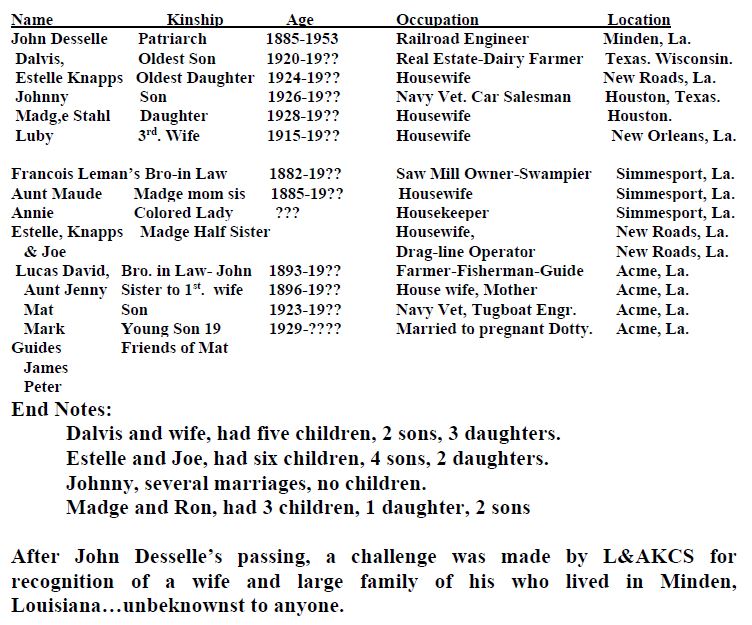

CAJUN

Those of French descent living in bayou parishes of Louisiana often refer to themselves as being “Cajun”, their loose translation of Acadian, (drop the first ‘a’ leaving ‘cadian’). As a result of France’s defeat by Great Britain in the Canadian War 1754-1763, often referred to as the French and Indian War by the Colonists, remnants of the defeated Acadians continued to harass the English.

In retaliation for the Acadian’s refusal to pledge alliance to the British crown and Anglican Church, members of that sect were expelled from the Eastern Maritime Provinces of Canada. Most were scattered along the coastal regions of the Southern Colonies and Caribbean. Spain offered refuge to fifteen hundred if they would offer their hunting, trapping, and farming services in exchange for land grants in Southern Louisiana.

It wasn’t easy for the Cajuns; they were very clannish, protective of their ethnicity, religion, and culture.

Their very existence depended on each family member contributing fully to their survival. They were constantly at odds with the New American government, refusing to give up their French culture and language. A large contingent of Volunteer Cajuns did help get their revenge on the Brits in the War of 1812 at the battle of Baton Rouge. In the early twentieth century, laws were passed to forbid the use of speaking French at public schools; their children were punished for doing so. The Catholic Church established academies throughout the area to help ease the transformation of the languages.

The Cajun faced another obstacle, Acadian’s of the ‘upper crust’ who fled France during the religious uprisings, settled in Nova Scotia bringing their wealth, and aristocracy. They were also expelled and refused to associate with the laboring local Cajun. This snobbish and arrogant dislike lives on…even to this day.

Another matter of misconception; ‘Creole’ is often described as being related to the Cajuns because of their similar family lifestyle, use of bastardized French language, often Catholic, similar food spices and preparations, and their distinctive rhythm in music. But, the original Creoles of French descent propagated with the Spanish and Germanic heritages, unlike the Cajuns who preferred to mix with their own ethnicity. Thus, we come to the evolvement of…

Coon-Ass

Just because I married a young girl from the Bayous of Central Louisiana didn’t give me the right to utter the name ‘Cajun’ let alone, ‘Coon-Ass’.

World War II had just ended and after six months training I graduated from the Army School of Marine Engineering at Lake Pontchartrain. The day after I received my shipping orders to the Pacific, Madge and I decided to get married. Because of the one-year contract I signed, I was obligated to ship-out to Manilla

where I was able to finagle my way out of the contract, losing any hopes of an Engineers License, plus, agreeing to work my way home (without pay!) on the SS William F. Fitch, an old rust bucket. On returning, we landed at the Oakland Army Port of Embarkation.

I had my new wife fly out to meet me in San Francisco while I camped out in a hotel. After reviewing our financial situation, considering the cost of transportation to go down to meet my family in Los Angeles and then the cost of going back to Louisiana, plus expenses for food and lodging, we figured it would eat up most of our savings. I decided to make an offer on a ’39 Dodge 2-door sedan owned by one of the hotel’s guests who was in desperate need of cash. He accepted my offer. We drove the hell out of the car for nearly two years.

I worked as an outside machinist, repairing steam engines and boilers out of I.A.M. Local 37, on the waterfront of New Orleans. Work schedules ran hot and cold, so it gave Madge and me the chance to visit her huge family scattered all over Cajun country; Marksville, where she was born, Bunkie, New Roads, Acme, Simmesport, and Bordelonville.

These were not shirttail relatives but brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins. Their family gatherings, numbering into the thirties and forties, were like I’d never seen or heard of before. Everyone brought plenty of food; a lot of crabs, crawdads and shrimp piled in mounds on the tables…and a highly seasoned stew they called Filet Gumbo and rice. Of course, there was always plenty of beer and homemade wine.

Music seemed to be the family’s favorite social activity. Everyone played an instrument…one of the kin played spoons and sticks like a drummer of a symphony orchestra; he beat on anything that made a good sound. There was a slide-guitar, squeeze-box (accordion), fiddle, banjo, harmonica and of all things, a wash-board that was strummed on by a fellow with sewing thimbles on the ends of his fingers. The dancing began, mostly a two-step with a waltz thrown in now and then, and only ended when the band broke up well after midnight.

The Patriarch of the family was my father-in-law, John Desselle, twice widowed. Once retired from the L&AKCS Railroad as an Engineer, he was called back for the war effort and only recently had retired again. His present wife, Ruby, a widow, was a Bordelon from (of course) Bordelonville. It was said the old man married her only to care for his son Johnny and my wife Madge, who were teenagers at the time.

Many of the clans’ menfolk worked their own farms or sawmills, and a few commercially fished the Red and Black rivers. One family, the David’s (pronounced Dah-veed) consisted of farmers, fishermen and swamp guides for Oil Explorationers.

One of my favorite families to visit was Madge’s older half-sister Estelle Knapps, who lived near New Roads. Her husband, Joe, was a long-time dragline operator who was under Civil Service contract for the Army Corps of Engineers. He tried every way to enlist in the military services but the Corps put a special deferment on him because they needed his talent and experience on the draglines.

Joe invited me to spend a day ‘or so’ at his river levee rebuilding site, where a fault was found and could have given way at the next high-water stage. It was quite an operation. There were two huge cranes with tractor treads, facing each-other, working atop a levee. They had already clam-shelled down to the fault areas and were now filling the huge gap by slinging their dragline buckets out into the river, a talent few men have ever developed. It required the art of timing, quick decision making and a good eye to see that the wires were clear and taut. They swung their 100-foot booms to the dry side of the levee, with the seven-yard bucket dangling at the right height, then rapidly swung the boom around, releasing the brake, and let the bucket fly…praying there were no snags in the wires. They then dragged the bucket back up the levee, dumping the mud and sand where needed. A Caterpillar, towing a large sheep’s foot compacter, pushed the muck around with a huge blade in front.

A couple of hundred yards from the working area were bunk-houses, galley, rec rooms, and johns…all atop sled-like logs that were towed with the tractor to keep-up with the work crew. I didn’t realize that I was to be held captive for four days,with 16 other men as they rotated shifts around the clock, inching their way up the river.

The cook and his baker kept us well fed. Many of the locals came to watch the operation, bringing chickens, eggs and fresh meats as a show of gratitude for helping to save their farms.

One of the strangest incidences I had was on our first visit to my wife’s Aunt Maude, elder-sister to Madge’s mother, who lived in Simmesport. We parked in front of a nicely landscaped, freshly painted white house and walked up to the front door. Then all hell broke out; I’ve never heard so much screaming and yelling…the door flew open; an elderly black woman grabbed my wife and hugs and tears overcame the two of them. I thought…this is my wife’s Aunt?

Several minutes later when things settled down, the black lady led us to the kitchen, sat us down and within a few minutes, starting with iced tea, plates filled with goodies of all sort were put before us and I was finally introduced. Come to find out, when

young Johnny and Madge’s mother died, this lady became their mother for nearly five years while they lived with Aunt Maude.

A second very strange incident came about at dinner. Aunt Maude, now in her late seventies, wracked with arthritis, was already seated at the table. Madge and I sat down. I noticed there was no place for the black lady to sit and I told her to bring up a chair and sit.

She replied. “Mister Ron, we don’t do that here, it’s disrespectful.”

I had a hard time understanding what happened, “Disrespectful to whom?”

Aunt Maude’s husband, François Leman, was a proud ‘Swampier’ who owned and operated a saw mill about fifteen miles up where the Atchafalaya River and the old Red River came together. He came in late from the saw mill. We sat together and talked for most of the evening while sipping home-made wine. Aunt Maude completely ignored us while she talked to Madge…as she was a strict teetotaler.

The next morning, bright and early, Frank invited me to go to the mill with him. We loaded his stake-bed truck and as I got in I noticed the heavy screen over the windshield. I questioned him and his response was, “You’ll see in a few minutes.”

Our hard-packed oyster shell road changed to a loose lumpy gravel road with deep ruts and pot-holes. Frank, driving about 35 MPH, saw a tanker truck coming from the other direction that looked like it was doing at least 60. It didn’t slow down, and passed us, spraying gravel in every direction.

Frank said, “I complained to the drilling company. Their response was. ‘Give me the date, time, place and truck number.’ Hell, they go so fast I couldn’t read off the truck’s ten-number line fast enough.”

When we walked into his mill I smelled a God-awful odor, much like vomit or a fart. In a joking way, I asked Frank what he had to eat the night before. His response was, “That’s the smell of money. When Oak sawdust gets wet and ferments, it gives off a fragrance that to me is like fine wine.”

I couldn’t believe the primitive machinery setup; A six-cylinder gasoline engine with a gearbox, clutch, and a five-foot diameter flywheel, a six-inch-wide wooden pulley and leather belt running to another pulley, then to another wheel under a twenty-foot-long table, driving a six-foot diameter saw disk with about sixty to a hundred teeth.

With a log sitting on a ramp made up of many rollers, it was a three-man operation. Two of the men prepped the log; trimming, sizing, and paralleling one side with an adze. A lanyard from a block and tackle helped to draw the log through the saw as the operator, with a yoked pole, forced the log against the saw’s fence.

Frank said his most profitable endeavor was in sawing Cypress planks. His long-time local swamper’s felled and trimmed the trees, towed them out of the swamps, then rafted them up and floated them down water-ways of their own making, to his saw mill.

A boat that operated in the area of the upper Atchafalaya River had many tasks. In the early morning the boat would pick up certain species of fish, such as Drum, Buffalo, Bass and Catfish from the fishermen’s pens, weigh each group, leave a receipt as to each group’s weight and the previous day’s market price. They left unmarketable fish in the pen.

The fish-boat also acted as a water ferry along the river, transporting people and freight from one stop to another. When the boat scheduled a trip down river, he let Frank know so he could arrange to haul a load of finished lumber down to a yard at Melville, where trucks loaded up and shipped where-ever.

While showing me around his mill, Frank asked if I would mind helping him set up the grinder used for sharpening saw blades.

Off to one side of the saw tables was a sheltered area with a fabricated ‘A’ frame standing five feet high, welded to a base plate and a 1/2” thick, 6”X18” face plate welded to the frame.

We attached a heavy duty flanged spindle into one of several holes drilled up the face-plate. Frank brought in two circle saw blades; one was three feet in diameter and the other was four feet. He locked the three-footer on the spindle, spun it to see if it was balanced and ran true, then took a gauge to check the ‘set’ on the teeth. He took a clamp-like tool from his chest and began squeezing a tooth to the proper set. Next came a six-volt electric grinder, a small contraption with a four-inch diameter grinding wheel set on an angle. He bolted it to an arm off the ‘A’ frame. A ball lever with a half-inch round bar, a hook on one end, slid through a saw-tooth, two locations below the tooth needing sharpening. He drew the bar back hooking the saw and drawing the blade back about 1/32” to a cushioned pad, then pulled another bar back and forth, adjusting the grinder until it sparked.

The same procedure was repeated 40 or so times for nearly a 20-minute cycle and then again to make sure every tooth cut the same. Frank said he sometimes had to sharpen blades at home after they hit stones in the logs.

I suggested he try using “Hoe” Carbide inserts, to which he replied, “The cost of a 110-volt generator, the carbide tips, plus silver soldering, a 110-volt grinder needed to drive the six-inch diameter, and very expensive diamond wheels to sharpen the tips, costs more than I make in a year.”

Overall our visit was great, even though I didn’t understand a word of French that was spoken at the mill.

A visit I always looked forward to was way off the beaten path. We had to drive up to Jonesville, then take a highway towards Natchez, by-pass the first road going south, and make sure to take the second because if you missed and took the third, you’d drive for 30 miles to nowhere. It was known as the logger’s road to the hardwood forest. We were sure we were on the right road when, five miles down the road, we saw a sign that said “David’s Camp” and an arrow with “Twenty Miles”.

The trip itself was interesting, the first ten miles was hard packed oyster shell, a bit dusty. The next ten was gravel with many pot holes. On

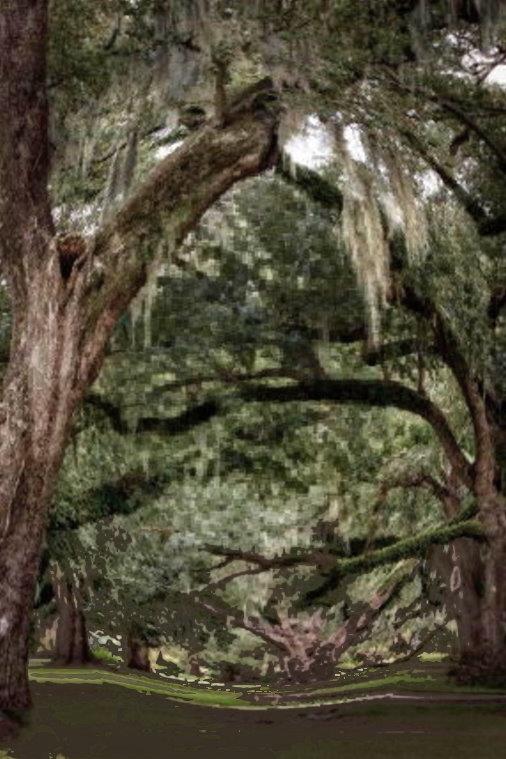

meeting the occasional car, we both slowed to a crawl as we passed. The view of lakes and swamps, with their heavy growth of trees was beautiful. We must have made a loop of five miles; I swore I recognized a house we had passed a few minutes before.

We came into a wide-open pasture land where we saw several patches of different vegetables growing; many rows of 6-foot high corn, turnips and other greens. Around the corner of the road was a large two-story house, a bungalow, and a barn. Across the road was the huge levee, maybe forty feet high.

There was a small post with an arrow pointing to the house on the opposite side of the road with “David’s Camp” painted on it. We turned in and drove up to the house and just sat there, waiting or hoping someone would come out. We sat awhile longer, then I got out and climbed the steps to the porch, I knocked on the door but got no response. I called out, still no answer. Madge went in, came back out and said no one was at home. She went to the bungalow in the rear; no one was there. I began to think things were getting a little creepy. I went to the car and blasted the horn several times, the only thing I disturbed were a pack of dogs that came from everywhere barking their heads off.

I walked across the road and climbed up the trail to the top of the levee. What a view…the Black River was probably at its widest point here and across the river was a major swamp area with stubby tree growth. Another river, possibly the Red River, appeared to be joining the Black River a mile or so down-stream.

I saw several fish pens, twenty feet or so out in the river, no doubt anchored out with a line, then tied off to a large rock on the levee. What I saw that was so interesting was a tar pot eight to ten foot in diameter; I wondered what it was used for.

As I started walking down the side of the levee I saw a string of cars and trucks coming down the road. About six of them turned in to the David’s and the other four or five continued down river.

Madge came out of the house and the hugging began; there must have been 15-20 adults and kids, all trying to get in their hugs.

After a half-hour of introductions, the group started breaking up. Everyone had something to yell out to another. “I’ll bring up the boat about six.” And to another… “It’s your turn to take the kids to the bus stop in the mornin’.” A man, maybe a couple of years older than me, invited me to visit his family at the bungalow out back after finishing our visit here at the big house; his wife and three kids followed him out.

The Davids (Dah-veeds) were a large family. The mother was Madge’s Aunt Jenny, a sister to John Desselle’s first wife. There were three sons and two daughters, all married and with kids of their own. Everyone worked, be it Fishing, Swamp Tour Guide or Farmer.

Mathew ‘Mat’ was recently discharged from the Navy as Machinist Mate 2nd Class and now worked part-time on the fishing boat as Engineer. We had a lot in common and became fast friends. It was he who asked that we stop at their house, the bungalow, after visiting with his parents.

Everyone congregated around Aunt Jenny and Uncle Luke’s large kitchen table, which had gauze-like tents in the center covering assorted foodstuffs. Aunt Jenny brought out a plate of fresh Baguettes slathered with butter, a jar of home-maid relish and a thick slice of smoked ham. A large mason jar of chunked-ice tea completed the feast. I couldn’t have picked a better meal had the menu been a yard long.

Uncle Luke explained why everyone was gone when we arrived. “Jimmy Davis is running again for Governor and threw a free picnic and hoe-down up at Bayou Cocodrie. Must have been close to a thousand people there to listen to him sing. There’s not many people that can drag that many Cajun’s out of the swamps.”

“We’ve been without electricity for the past week, thank God for the fish boat; he brings us block ice to carry us over. By the way, are you up to goin’ fishin’ in the morning? I could use the extra help.”

“I’d love to, what time?”

“I’ll come knock on your door; we’ll have a bite to eat. Let Madge sleep in, she can join the women in the morning.”

I took that as a way of saying goodnight. I yawned, stretched, stood and bid Uncle Luke a goodnight.

We went to Mat’s house, which had Coleman lanterns going all over the place. Madge and Mat’s wife and kids were out on the raft, fixing our bed for the night. Mat poured our Mason jars full of cool beer; I questioned, “Why all the Mason jars?”

“Let me show you something.” He got up, went to a pantry and swung out two doors where I saw rows upon rows of Mason jars filling the shelves; vegetables, fruit, meats of every kind. Pint and quart sizes, round and square, clear glass and colored; I saw pickles, corn, string beans, berries, peaches.

He smiled, “The women go hog wild when canning season comes around. I’ve seen them stay-up all night, going through the different processes.” I noticed a door-jam fascia, recently painted, with lines grooved across with dates and asked him if the lines represented the height of his kids and family.

Hell no, that’s how high the water was in the house at different flood stages.” I found it hard to believe that people would remain in this spot, after losing so much in a flood, and questioned him, “Why do you stay?”

“Generations of my family have worked hard to clear this land. For many of us, it’s the only way of life we know. We’re not about to abandon the highest ground within 20 miles to let someone else come in and profit from our loss.”

To myself I thought, “And to think I once thought they were clannish in the negative sense.”

“If you’re going fishing with my dad in the morning you better get some sleep, he starts early.” Mat walked me out to the raft. It had a house sitting on 5 feet diameter logs, maybe 20 feet long with a heavy chain linked to a bridle around two large Cypress trees. “My dad and his dad built this raft when I was a small kid after a flood wiped them out. The flood took everything, the house, barn, all the hogs, chickens and one of his most valued possessions, his bees. Damn good thing they were warned that the levee was about to give way upstream, they were able to load the old truck and farm wagon with whatever they could grab hold of and took off up river.”

The house was 10-feet wide, by 14-feet long, very clean and well laid out; twin beds along one wall several chifforobes, a dresser and a cushioned-top box that I took to be a commode. In the corner was a small pot-bellied wood stove. Out of curiosity, I opened a chifforobe. It was stacked with loaded mason jars full of preserves.

Madge was already in bed. I spent several minutes, searching for spiders…I have a personal fear of spiders…not seeing any, I climbed into bed and instantly fell asleep.

I was rudely wakened in the middle of the night with pounding

on the side of the house; I saw a flashlight beaming across the windows. I sat up yelling, “What’s the problem?”

“Time to go fishing, if you’re still interested!” came the voice from outside, “Come to the house and have breakfast.”

“I’ll be there in a jiffy.”

Madge sat up, mumbling, “What’s happening?”

“I told the old man I’d go fishing with him this morning; I didn’t think he meant the middle of the night. No need for you to get up now, go back to sleep.”

At Mat’s, coffee, oatmeal with raisins, honey and a pitcher of fresh cream sat on the table in front of me, along with a platter of pancakes and jam.

“Eat up. It’ll be noon before we get anything more to eat,” said Uncle Luke as he tossed me a bundle combination of boots and waders, adding, “Put these on, fishing will ruin those duds you’re wearing. Don’t lose the gloves, you’ll need ‘em.”

Somebody stomped their feet on the front porch, knocked on the front door and came right on in to the kitchen and sat down at the table. He looked at me and uttered “Mornin’.” Aunt Jenny, put a bowl exactly like mine in front of him. Without any hesitation or thanks he whined, “Come on mama when are you going to start baking those cinnamon rolls again?”

“When you get your wife to start fixing your breakfast,” She responded.

With breakfast over the three of us hiked the levee just as dawn began to break. A large bateau was waiting. It was boat resembling pontoons that the Army used for bridging rivers; it had a blunt bow, was six feet wide, 18 feet long, with a 30hp. Evinrude outboard on her stern. We climbed aboard and took off down river.

We came on to some corks floating near shore. Uncle Luke started pulling in the lines until he brought up a large, tarred one-inch line. His son Mark worked the boat towards mid-river as his dad, seated mid-ship with me in the bow, hauled in the line over a roller on the bow, then handed me the line and ordered, “Pull.”

I pulled and pulled, as his son worked the boat upstream until I

brought up the first gigantic hoop. The hoop had to be 6 feet in diameter, with heavily tarred nets draped around it. The old man stood, grabbed the hoop, fit the rim in a notch on the gunwale and rolled it aboard and plopped it on the athwart-ship planks. I just stood looking at the empty hoop trying to figure out how we were going to catch fish, when the old man broke my spell. “Get to work. We have five more hoops to go.”

I started pulling on the netting until the next hoop appeared. We went through several cycles, until the load got heavier. Thank God, he had given me the gloves. I was concerned about the strain on the netting, afraid that I might pull it apart, when the old man grabbed a hand-full of netting and together we got the last hoop aboard. Over the side was the largest bundle of fish I’ve ever seen.

Mark joined me in pulling the net aboard while his dad pulled fish out the net until we could start dumping fish from the net down through the throat space of the six hoop-nets.

While Mark sorted the fish by tossing them into the sectioned off compartments, the old man mended a ripped area in the net with a bone mending needle, tying knots into squares faster than I could count.

The hoops fascinated me; they were made of laminated, dark and light wood, steam bent and an inch and a half in diameter; as carefully made as a fine piece of furniture. I noticed nodules of lead incrusted on one-third portion of the hoop.

Everything was checked over and as we drifted down river in the current the hoops were sent over the side. Amazingly, the whole operation didn’t take more than twenty minutes and we were off to the next of six sets, with about 250 pounds of assorted fish aboard.

We were at the fifth set, I was pulling in the third hoop when everything slackened, the hoop came aboard minus most of the netting, the old man grabbed a handful of net and called for his son to come help, we slowly inched the net aboard along with the next hoop and a huge bundle of fish. They latched onto the money fish, letting the trash-fish flop free while the old man tied several lines from one hoop to the other and tossed the whole set adrift, announcing, “We’ll come back for it when we finish the last set.”

We finished emptying the hoops, picked up the damaged hoop set and headed for the pens to unload the day’s catch of nearly 600 lbs.

Mark selected what fish were worth putting in the pens and released about half of this morning’s total catch, consisting of small Carp, Gar and several Turtles.

It took the three of us to lug the damaged set to the top of the levee. Uncle Luke cut away much of the netting, freeing up a hoop and asked me to roll it to the table next to the tar vat. I inspected the hoop and saw the pretty laminations and finish, Luke saw me studying and said, “When the war started I couldn’t get any steel rods, so I built a jig. I had an old eight-inch diameter steel oil-well casing eight-feet long that worked great as a steam tank. Frank, down at Simmesport, sawed all the assorted quarter-inch thick by two-inch wide wood strips. When we made our first hoop-set everyone wanted me to make hoop sets for them, but on a much smaller scale like three and four- footers.

“Good cordage for the nets was hard to come by. I heard that in England and Canada they tarred their nets, which gave them strength and longer life. I taught the women to make nets; we had a pretty good business going.”

The next morning, I went with Mat and his dad to check on the small herd of cattle and several pens of hogs. We loaded up the truck with several bales of hay for the cattle and for the pigs, a couple of tubs of what they called “slop”; a mixture of corn, milk and hay that stunk like hell.

We took off on a dirt road maybe a quarter mile behind the barn and came to another clearing. About a dozen head of cattle were grazing within a fenced area, and beyond that were the hog pens, near a swamp. We stopped at the pens and poured the slop into wooden troughs. Mat took a probe and jabbed the pigs, making them get up and walk around so he could check them over for sores. He said that a gator tried to get to the hogs a few weeks back and he threw a couple of cherry bombs at them, chasing them off.

At dinner, Luke asked if I was up to going fishing again in the morning. He said it was a different kind of fishing…and maybe we could also do a little squirrel hunting. I asked, “What time do I have to get up?”

He responded, “About the same time as we did this morning. Wear the same outfit as you did when fishing with my Dad; we have to wade across some swamps.”

The next morning about the same time and procedure as with the old man, rapping on the side of the house. I yelled out, “Coming!”

The lights were on at Mat’s house. I stomped my feet on the porch and went in. Two new faces were at the table and they were just finishing up their breakfast. Mat put a plate of ham, three eggs and a hot corn pone in front of me; butter and honey was on the table. I was introduced to the newcomers who were lifelong buddies of Mat and were going hunting with us. “You coming to visit with us gives Peter, James and me the perfect alibi to get away from the wives and do some recreational hunting.”

Mat’s wife, Donna, poked her head in the kitchen and with sarcasm dripping from her voice, responded, “You don’t need no damned excuse to go anywhere. You can pack your bags and git! Just remember I get the house, the kids and whatever the Lawyer can squeeze out of your hide.”

Everybody in the room froze. Mat went to the door and pulled Donna through, grabbed her in his arms and gave her a big smooch. “Don’t ever threaten me again or I’ll tell everyone where I met you.” Everyone, including Mat and Donna, roared with laughter.

We went out to load Mat’s pickup. There were several shoulder strapped bags with fishing rods, lever action rifles, a Militarized Springfield 30.06 bolt action and his two faithful dogs already perched on the bed of the truck. I hopped aboard the bed with Pete. James sat in front; it was his property we would have to go through, to get to the swamps. About three miles down-river from Acme we turned off and went a mile or two

into the swampy area. Good thing Mat had surplus military mud tires with the knobby treads, my car would’ve never made it.

“This is where we get off. Grab a bag and start wading, James will lead the way.” We must have crossed over three ponds of water, two to three feet deep, crossing to patches of land each about fifty feet long. The dogs took off, barking their heads off.

Mat said, “They must have picked up the scent of a deer; we may not see them again for a day or so. One time they were gone for three days. They came back limping, with their hide full of open sores, patches of missing fur, tired and hungry, lookin’ like they might have met up with a bear or a wildcat.”

I didn’t know if he was trying to scare me but it did make me pay attention to my surroundings. We came up on a boat about 12-feet-long they called a pirogue. I thought it looked like a west coast dory, sharp bows, vee sides and flat bottom. A line covered with moss and leaves hung from five feet up the tree holding the boat. Mat and James, lugged the pirogue to the water and rinsed it out.

James grabbed a pole and the bag with the rifles; then he climbed aboard. He took a coil of rope out of the bag, tied one end off on the stern, with Mat holding the other end, and started poling to another patch of land fifty feet or so away. He unloaded and shoved the boat back. This was repeated, over and again until we were all across the water to the patch of land. Then, surprisingly, they loaded up the boat and ordered me to grab one side and start carrying. We lugged the monster maybe a quarter mile before we took a break at the edge of another patch of water. Mat broke out the coffee thermos, then dug deep in his knapsack and came up with a bottle of creamy rum. I’ve never heard of rum and cream before, but in coffee it sure hit the spot.

“Where to next?” I asked.

“James, you’re smallest, take the bags across, come back and take Ron. Come back and get me then you can go back and fetch Pete.”

Mat turned to me and asked if I’d ever fired off cherry bombs. “Only on the 4th of July, why?”

“I’ll give you a couple. If you see any Moccasins sneaking up on you, don’t hesitate to use them.”

That got my attention. I wondered why he carried a .45 in a shoulder holster. Now I knew… just in case.

It was the longest crossing of water so far. We skirted by a few small shoals of land, so James could use the pole, and finally came to a larger island with a massive forest of trees. James got out and searched around, finding nothing of concern, he bid adieu and went back for the others.

A moment of anxiety came over me. I remembered how we used to initiate newcomers to our beach in Malibu. A couple of us had skiffs and invited the newbies to join and participate in a mock Pirate battle, we even used BB guns. After their side invariably lost, we perched and abandoned the newcomers on a rock called Camel’s Hump for a couple of hours while the tide creeped up the rock. I had a most visual memory of the occasion, because I was once a newbie. Could I be going through the same ritual out here in the swamps? I lit up a cigarette, took out a cherry bomb and toyed with the idea of lighting the fuse.

I snapped out of my anxiety and took notice of my surroundings. Ahead of me was a massive cavern created by the tree tops coming together. It was like a giant Cathedral. Trees a hundred feet high, very little sun-light coming through, with almost barren trunks, the ground had little to no growth with the exception of moss. For a moment I felt I was the only person left on Earth.

I guess I wandered farther than I thought. I heard someone calling out and I looked in the direction the voice came from. The other men were tiny images at the far end of the cavern. What an experience.

“Now you know what guides are for,” Mat said. “Several times we’ve been called out to find lost green-horns. Once or twice it was too late. One group had us set up camp and told us they could maneuver around on their own, with all their maps, charts and information. A week later the Oil Company hired us to go look for them. We found them but the elements had taken their toll. They hadn’t prepared themselves for the isolation, the ‘skeeters, gators, snakes and nocturnal animals that root or hoot at night. Those once fit men became frail, weak and feeble old men in just a few days in the wilderness.”

I confessed to Mat of my anxiety attack and how I thought that they might have planned to put me through an initiation to see if I was up to it.

“Hey, you’re family,” he bellowed. For the first time I was accepted as ‘kin’.

Mat said, “This is the area where we usually pause to evaluate our clients for the rest of the trip; if we don’t think they’re up to it or capable, we let ‘em know it and suggest alternatives. We tell ‘em to bring only what we think is necessary. They don’t listen and we wind up leaving over half their supplies at the houseboat. Maybe that new-fangled ‘Helicopter’ will put us out of business but until then, this is all they have.”

“I wish we had those helicopters in the Pacific when I served on a 112-foot-high-speed Army Ambulance vessel. We transported the wounded men who were involved in mopping up small islands and perimeters around New Guinea and the Philippines to the hospital.” Then I asked, “Where to next?”

“We’ll set up camp over there,” Mat said, pointing to a clearing near a pond with a lot of bushes and old logs laying around. The three men set out a ten-foot by ten-foot tarp, unloaded the bags and took off in different directions. Then it hit me they had to go relieve themselves. Not so, they came back after 15 minutes with twigs and branches to start a campfire. The rifles and fish rods were laid out. Pete saw a goose near the shore about two hundred feet from us, took a shot with the 38.40 lever action, missed, and then took a lot of riding from his buddies.

James asked me if I was a good shot. I replied, “Fair to middling.”

“Do you see those two turtles on that log? Do you think you can hit one?” It was maybe 200 feet away.

“If I shot it how would we get it?”

“If you hit it I’ll swim and get it.” Select your weapon.”

I looked over the three rifles. Not being familiar with the Winchesters, I selected the bolt action.

“You would select the rifle with the most expensive cartridge to use. That costs 20 cents a pop.” “Are you pissed at me for something?”

Mat interrupted. “That’s James normal attitude. Sometimes I have to pull him aside and make apologies for him.”

“I was just wondering if it was something I said or did.”

I picked up the rifle, checked it over, flipped the bolt and inched it back. I slipped my right arm into the G.I. sling and took a quick test sight, I flipped the sight leaf up, slid it down to zero, flipped the leaf down, then set the rear-sight for 100 yards, I checked for windage and went into the special stance I use, with my right elbow resting on my hip bone, my back contorted but under control. Everyone went into hysterics. I told them to shut up, I was trying to aim. That only sent them into more laughter. I thought of laying on the tarp, but that would’ve brought on more ridicule.

BLAM!

Everything went quiet. I searched for damage to the turtle. Seeing none, I began thinking that I had missed when Pete yelled, “You blew his freaking head off!” Then turning to James he said, “Start swimming, we’ll have turtle stew for lunch.”

James countered, “I can’t believe what just happened! He actually hit the target. He blew his freaking head off, while all tied up in that knot! Hey Ron please, let me apologize. I was teasing. I was just trying to get your goat, to rile you so you would miss.”

Mat asked, “Where in hell did you learn to shoot like that? They didn’t teach that in the Army.”

“I only have one good eye. I trained myself to shoot left-handed. I picked up some points on the 30.06 from a sniper I bunked with from the 41st Infantry on Biak.

I must admit, I felt ashamed for killing the turtle and nobody felt the need to go get and prepare it for a meal.

It was too late to squirrel hunt so everyone set up for fishing; bass fishing. ‘Large Mouth Bass Fishing’; the guys said it like it was some form of important ritual. They each grabbed a small rod and reel and attached their own personal preference of lure. Mat made up a rig for me and asked if I’ve fished for Bass before. I said, “I’ve ocean fished, lake fished and stream fished for Trout. Is there something special about Bass fishing?”

He responded, “Everyone has their own technique, some use live or dead bait, spinners or chum. Others cast the line out then drag, jerk and weave it back in. To some it’s an art form. I like the jitterbugs. I fit a new Hawaiian Jitterbug to your line.”

I watched the others go through their routines, hoping to pick up a sure-fire tip. I soon tired of watching their futile attempts so I thought I’d wet my line, I cast through an opening in the brush. Damn! A hang-up on my first attempt. Mat, fishing about 20 paces down the way, saw my predicament. He signaled a whipping motion. I tried, but the limb wouldn’t give. I got aggressive and whipped the hell out of it. The branch sprung up, sending my Jitterbug to a clump of branches closer to the water. The Jitterbug hung about six inches above the water. As I tried to whip again I noticed several fish jumping at the lure. I called Mat to come and help me; I didn’t want to lose his expensive Hawaiian Lure.

He said. “Give it one more good yank.” I did. He was amazed at how all the fish were fighting to get to the bait. He called for the other guys to come see how the fish had gone crazy.

I thought I’d give it a healthier yank…the jitterbug went up then dropped back to the water. I was about to reel the lure in and try again, when something almost took the rod out of my hands. The line was running! I tried to put the brake on whatever it was and it almost pulled me into the water. It went off to one side, clearing the limbs and bush…it was running all over the place. The fish relaxed for a moment. Mat told me to hang on and try reeling in real slow. I wasn’t used to this small reel. At home in Malibu I had used a 200 Penn, wide-spool Surf-caster with a star drag and a limber 10-foot rod with roller guides; quite a difference.

After ten or fifteen minutes of shouts and commands from the pro’s, I finally brought her in.

James had a small hang scale. The Bass weighed 7 ½ pounds.

For some reason, almost like letting the air out of a balloon, the enthusiasm of the group vanished. As if everyone went into the same mind set, we started gathering up the camping equipment. Pete rolled up the tarp and stuffed it in a bag. Mat cleaned the 30.06, the tackle was stuffed in the bag and we were ready to travel.

I asked, “Where to now?” Thinking they might’ve had another camp spot in mind.

“Home!” Almost all said in unison.

“But I thought we’d have my Bass for lunch.”

“Ron, I may have caught larger Bass in the hoops, but what you caught may be a light tackle, fly-fishing ‘Trophy’ for this area. Before anything is done to that fish, I want a picture of it alongside the tackle and Hawaiian Jitterbug,” Mat answered.

“You mean I have to lug it all the way home?”

“You caught it.”

I found out that the first Friday night of the month in Jonesville is Family Night, Acme Night, Grocery Shopping Night, Beer Drinking Buddy Night and for the young ones, Hamburger, Wiener and Shake Night, all rolled up in one outing. I heard mention of “Coon-Ass Night”. I didn’t get the drift or meaning of the inference and didn’t ask. There was even an outside movie area, with chairs, behind a roped off area, at a cost. The kids sat on the grass for free.

All the David family and extended kinfolk drove in to town in a convoy of several cars and pickups. Madge and I followed behind in our Dodge. Mark, Uncle Luke’s youngest son and his pregnant wife, Dotty, rode with us. Being the last in the convoy and with all the parking spaces filled, I drove back to the main drag and let Mark and Dottie out, Madge decided to get out also, so she wouldn’t have to walk so far.

I parked out in the boonies and had to walk some distance to get into the shopping area. I saw a barber shop still open. I needed a shave and a haircut, so, what the hell, I popped in. Several men sat in all the chairs, deeply conversing in French. A man I took to be the barber, got up and motioned to the vacant barber’s chair and offered, “Monsieur”.

I said, “Thank you,” and sat.

“Parlez-vous Français?” he said, as he started clipping with scissors.

“No…I’m visiting with my wife’s family down at Acme.”

“May I ask what family that might be…maybe the Dahveed’s or the Howe’s?”

“David’s,” I was feeling a little uncomfortable with all the questions.

“Ah! Lucas, my old Coon-Ass buddy. We went through many times together. We went to the same school at New Era and we both joined up together for the Army in ’17. What memories. He’ll probably come in later to say hi.”

How fortunate to stop in and meet an old friend of Uncle Luke. I learned more of the David’s while sitting in the chair for 15 minutes than I did staying with them for 4 days.

I bid the barber adieu and sauntered down the main drag, nodding my head at each passer-by. Across the road was the park, jammed with people. I couldn’t get over how crowded this shopping area got. The barber said the town was jam-packed on Saturday from noon ‘till midnight with shoppers, but Friday night was for Coon-Asses.

I came onto a brightly lit area in front of a “Piggly Wiggly” grocery store. They must have sold everything; people were lugging out 50-pound sacks of flour, rice, animal feed and what-ever else you could think of. On the corner was a cluster of a dozen men around my age. As I approached I heard Mat yell out, “Here comes mister big shot. Hey Ron, come meet the gang.” Everyone was laughing and slapping my shoulders. I heard someone yell, “Good to meet you prune-picker!”

James had just enough to drink, He said, “This is the way he aimed to shoot that dammed turtle’s head off at 100 yards.” He bent over, using his arm as the rifle, did an exaggerated mimic of my stance, and yelled, “Blam!” Everyone roared, even I got caught up in James’ adaptation. Someone handed me a bottle of beer and the revelry took blossom.

People coming out of the store were trying to work their way through our gathering, so we moseyed down to a vacant lot. A fire was started, some sat on boxes or an old log, others plopped down on their butts. I handed Mat a ten-dollar bill and asked if he would buy a case of beer for the party. He countered, “Hey, this party is for you…I haven’t mentioned the Bass incident yet.

I noticed a Hot-Rod, similar to those on the streets in California, pass by. I took note of it because of the loud exhaust roar. Twenty minutes later I heard and recognized the roar again. I saw the coupe come down the street with its lights out, it slowed to a crawl, then someone yelled out “F—k Cajun Coon-Asses!” The car sped off with several of our beer bottles already in the air about to hit its rear end.

I asked Mat, “Why the controversy regarding the usage of Coon-Ass. Is it a slur on the Cajun people?”

“Depends on just who says it,” he answered. If you’re of the French elite, the Creole, they look down on those of us who migrated down from Canada and didn’t come directly from France. We hard-working Cajuns are proud of our French heritage, but also proud to descend from our Canadian and Louisiana kinsmen. To be a proud Cajun, French speaking, a Louisianan and a good Christian is a good thing. I proudly claim to be a Cajun Coon-Ass.”

“I wish I could be as proud of my own heritage. Since marrying into an ethnicity I never knew existed, I would be proud to claim kin to it.”

“Hey, you are kin to it. Welcome to the family, Coon-Ass!”