THE WHITE COCKADE

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

A

Rebellion IN SCOTLAND

AND IT’S EFFECT ON

THE

AMERICAN REVOLUTION.

By

RON STAHL

TO MY WIFE MARY

Without whose assistance and encouragement this story could not have been written. Most fortunately for me, what I lacked in grammar and the use of punctuations, Mary could contribute her vast editorial knowledge to ease the flow of words and thoughts so that the reader could do so in comfort.

Mary’s most poignant observation and used many times as we studied a day’s progress was, “If I cannot understand what you are trying to say, how do you expect the reader to do so.”

“WHITE COCKADE” was an adornment worn by citizens, politicians and the militant on their head gear and outer clothing to signify their loyalty to their cause, be it “Scotland for Scots”, support to “Prince Charlie” or “To worship as a Catholic.”

CONTENTS

A WEE BIT O’ SCOTTISH HISTORY

INTRODUCTION

LIST OF CHARACTERS

CHAPTERS:

The Bothwell Family

Battle at Culloden

The Fiery Cross at Glen Lyon

Uncle Andy McCall nee Andrew MacCullough

After the Battle (all the brothers are gone)

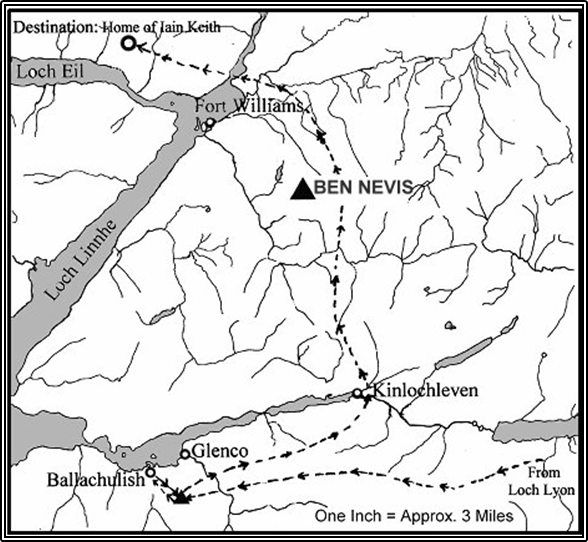

Escaping over Ben Nevis

A Reign Of Terror

Colonial Bark “Goodwill” and Captain Mackay

The wreck of “Maid o’ the Glens”

Passage to the Colonies

A Colonial Nightmare

A WEE BIT O’ SCOTTISH HISTORY

People, Dates and Places

Mary Stuart: (1542-1587) she preferred the French spelling of Stewart.

Mary became Queen of Scots (1542-1567). In 1565 she married Henry Stewart who was murdered in 1567. She married James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell, who was exiled after Mary gave up her crown to her half brother James Stewart. She was beheaded on orders of Queen Elizabeth in 1587.

Charles I: (1600-1649) King of Great Britain and Ireland only; not Scotland

(1625-1649). His Episcopacy riled the Scottish Covenanters (Presbyterian) and he was executed on orders from Oliver Cromwell in 1649.

Charles II: (1630-1685) also was a Catholic sympathizer, and also riled the

Covenanters. He claimed the throne in1649 and was Crowned King of all the British Isles in 1651.

James II of England (1633-1701) King of England (1685-89) was converted to Catholicism in 1672. His attempts to create harmony between the opposing religious orders stirred up bitter confrontations causing the King to lose most of his supporters. One of the most important acts in English history was the “Glorious Revolution” (1688-89), which subjected the king to laws alterable only by act of parliament. After a long struggle to put the throne above the laws James was forced to abdicate and run away to France. His daughter, Mary, heiress-presumptive to the throne in 1671, was a protestant and staunch supporter of the Church of England. She and her husband, William III were proclaimed joint sovereigns.

Mary II: (1662-1694) Ruled England from 1689 until her death in 1694.

She was married to William (1650-1702), Prince of Orange (Holland) in 1677. William III and Mary II ruled jointly from 1689 until 1694 and William III ruled alone until his death in 1702. During their reign the Highland Clans threatened restoration of Mary’s father, James II, and in 1692 the crown had all males of the Macdonald Clan, who were supporters of James, massacred at Glencoe. The predominantly Catholic Highlanders remained loyal to the Stuart King in exile.

Bonnie Prince Charlie: (1720-1788) the young pretender, Grandson of James II, son of James Stuart the Old Pretender. He was born in Rome and at 14 years, fought for Spain and distinguished himself at the

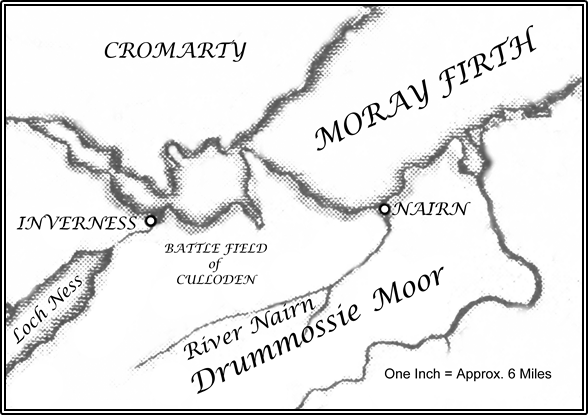

Siege of Gaeta during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748). France provided him with a military force, for his planned invasion of England, but his flotilla was destroyed by a storm in 1744. Charles was still able to make his way to Scotland landing on the Isle of Eriskay on 23 July 1745 and aroused the Highlanders to follow him in 1745 to their eventual defeat at Culloden Moor on April 16, 1746. He died in Rome leaving no legitimate children.

Jacobites: Catholic and certain Episcopalian followers of James II, King ofEngland (1685-89), who was dethroned. Jacobites (from the Latin “Jacobus” form of James) followed the house of Stuart and were most notably known for their defeat at the Battle of Boyne, Ireland by William III of Orange July 1, 1690. The Jacobites attempted to assassinate William III in 1696; many were caught and executed.

Jacobites fomented the rebellions against the English Crown in 1715.

A major battle at Sheriff-muir was indecisive, and later events ended in their total surrender at Preston. Again in 1745, while the English were at war against the French, the Jacobites rallied behind “Bonnie Prince Charlie” when he landed at Loch Shiel in Northern Scotland and raised an army of 5,000 men. Most were Highlanders and all were revitalized Jacobites. After several victories into the south of England as far as Derby the warriors, being undisciplined, soon tired of battle and characteristically broke ranks and headed for home with the excuses of, “the crops need tending” or, “my family needs me”. As in all their conflicts, they could only be counted on for one or two battles.

Charles’ forces were forced back to the far north where they met total defeat on the plains of Culloden Moor just a few miles southeast of Inverness in 1746, when faced by 9,000 English troops.

As a result of religious conflicts in Northern Ireland and the lowlands of Scotland many Presbyterians were forced to immigrate to Ulster, Ireland. They were given land grants formally belonging to the Catholic Irish in that area. These people were thereafter known as Scotch-Irish or Scot-Irish. Because of the harsh treatment of the Highlanders by their victors many migrated to the southern American colonies. Those that remained behind became ardent supporters of the Crown’s authority and contributed to the Monarch’s harsh dealings with the immigrant Scot-Irish in the American Colonies.

King George II of England, not satisfied with just a victory, had his son, the Duke of Cumberland who commanded the King’s Army in Scotland, continue to seek out and punish all Scots who supported Prince Charles at the battle of Culloden Moor in April of 1746, thus earning the name “The Butcher Cumberland”.

One of the more horrific deeds of the merciless victors was to murder entire Jacobite families (Clans) whose members were suspected of participating at Culloden (guilty….or not). This was reminiscent of the Crown’s attempt to cleanse the Highland MacDonald Clan (supporters of James II) wherein William III of Orange, reaping his vengeance at Glenco in 1692, as an example of punishment for not swearing allegiance to the throne within the allotted time for amnesty, ordered the slaughter of the MacDonald family members as they slept.

One hundred soldiers of the Argyll Regiment, most of whom were of the Campbell clan and bitter enemies to the MacDonald clan, were billeted with assurances of no hostile intent at the MacDonald estate for over a week. Forty MacDonalds were outright butchered and many more died from exposure to the weather. A child and a woman were the only known survivors.

Prince Charles and other Jacobite leaders who were able to elude capture after their defeat at Culloden had bounties placed on their heads, forcing them to spend the rest of their lives hiding from bounty hunters. No one betrayed Charles even for the ₤30,000 placed on his head as he hid out for five months on the Isle Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides, with the assistance of Flora MacDonald. Her exploits became legend in Highland lore, though she never heard from Charles again once he made his way to safety. Flora’s name will surface once again during the Colonial uprising.

INTRODUCTION

My original theme for this story was to create an adventurous and romantic interlude based on Scot-Irish influence during the 1770’s uprisings in America. As I waded through volumes of research material I found history of this period abundant with exciting episodes not generally known. Most documented recollections came piecemeal from letters or logs, usually after the fact, as few people directly involved had neither the time to write nor pen and paper to do so. When these assorted bits of information become woven into a chronological order exciting history seems to come alive.

Spain, because of her rightful claim to Florida, was becoming more concerned about the Colonial and English emigrant incursions into her Florida territory. The Spaniards supported anyone who would put a halt to these illegal encroachments, encouraging her ally, France, to intercede.

Bitter over the conflicts of her vast Canadian territory, France had much to gain if the Colonies were to take up arms against their British parents, thus allowing King Louis XV and his Mistress, Mme. de Pompadour, who was a powerful voice in the affairs of French policy, to concentrate on his other wars and intrigues on their own Continent.

It is my opinion and I do firmly believe that the survivors of the Highland Revolution of 1745 and the immigrant Scotch-Irish from Ulster, who suffered religious prosecution, high land rents and poor crop yields prior to coming to the Colonies, were largely responsible for inciting opposition to many of the English Kings’ mandates in their new found home. These Scot-Irish immigrants fanned the flames of hatred recalling their experiences of how the throne passed laws and proclamations to restrict privileges and rights on his Majesty’s own loyal citizenry, forcing them to flee their homelands, seeking new beginnings in the colonies.

You might ask why I chose to portray the Scot in particular. Read early American history and you will recognize many Scot and Irish names amongst our greatest Patriots whose roots can be traced to Scotland. Better yet, read of the troubled history in their homelands where seeds of revolution and discontentment with the English Monarchy were fomented.

The Highland Clans had a most colorful history even before the tales of Rob Roy, Wallace or Robert the Bruce. Fierce wars amongst themselves refined their battle strategies and weapons and honed their fighting skills to a point that even the ruthless Norse invaders found the Scots a force to be reckoned with.

They represent some of the oldest organized combat brigades since the Crusades and they may have been the world’s original mercenary military force. Every nation in Europe had the highest regard for their bravery. France bestowed the highest honors on their Regiments. Germany used several Brigades of Scot “Soldiers of Fortunes” and had high praise for their fierceness on the battlefield.

Within the “Terms of Alliance” with England after the Dutch won their Independence from Spain in 1678, there was language to establish a permanent station of 6,000 men of the “Scot Brigade” to act as a buffer between England and France. One hundred years later in 1776 when King George III requested their return so they could be sent to quell the colonial uprising in the America Colonies, the Dutch refused their request.

Promises were made that the Scots would not be sent to the colonies but only be used to relieve other English troops stationed in the Mediterranean. The English King even offered to hire Hessian troops to replace the “Scot Brigade” in Holland. Again the Dutch refused. King George was then forced to hire the Hessian troops and transport them directly to the colonies, many of whom consequently surrendered at Saratoga with General Burgoyne, others were captured by General Washington at Trenton on Christmas Day 1776 and many deserted seeking new identities in the Americas.

While visiting the port of Rosneath, on the Firth of Clyde during the Second World War, I became enchanted with the Scots and what I judged to be their quaint habits. I thought the country was as beautiful as any I’d ever seen and the people were as friendly as any people I’d ever want to meet.

In recent years I’ve walked the historic grounds of Culloden in the drizzle and cold rains, visited Fort George and many of the castles throughout the Highlands; even some that were private and not open to the public. What history those walls embrace! The back trails of Rannoch Moor and Glen Lyon in the autumn are beautiful. The high country around Glencoe was cold and misty and as my wife and I drove towards Mallaig the heavy rains created huge pure white waterfalls cascading out of the solid black rock mountains.

I conversed and interviewed people throughout the Highlands; I did sense a bit o’ the spirit of the Jacobites still flickering, I couldn’t tell if it was a sincere desire to rekindle the old flame or if it was just a romantic reflection of memories past.

A story has to have a beginning. So, after exploring a bit of the background of Scot history, I thought that the following narrative might just have been the time and place where the seed of the American Revolution germinated.

LIST OF CHARACTERS

- Nathan Bothwell: Husband of Mercy, father of Robert, William and Jonathan.

- Mercy Bothwell: (nee MacCullough) Wife of Nathan, Mother of Robert, William and Nathan, Sister to Andrew MacCullough (changed to McCall)

- Robert Bothwell: Eldest Son; Moved to the Colonies with his family.

- William Bothwell: Middle son; married to Mairi (Mary). Later changed his name to Bottle. Raised Billy as their son.

- Jonathan Bothwell: Youngest son; betrothed to Elizabeth (Tibby). Father of Billy.

- Billy Bottle: From an infant to a Colonial agitator against the English.

- Andrew MacCullough: Clan Sept, last of five brothers.

- MacAllister Family: Uncle Rufus, Neil, Duncan and Elizabeth (Tibby).

- Cousin Fiona and husband: Sheltered Mairi and Tibby during the uprising.

- Iain Keith: Bastard son of Scot Royalty. Officer in British Highland Brigade, deserted, changed name to Allan Cameron

- MacTavish: Blacksmith to the MacAllister family for forty years.

- Captain Mackay: Owner and Master of the sailing bark Goodwill.

- Duke of Cumberland and son of King George II: Also known as “Butcher Cumberland” after the battle of Culloden.

- Flora MacDonald: Protected Bonnie Prince Charles, taking him to the Island of Ben Beculla after his defeat at Culloden

THE BOTHWELL FAMILY

Of Dumbarton

Early history suggests that the Bothwell family had a kinship to the throne, but that distant side of the family fled Scotland to France when politics deemed it necessary and prudent to do so. The Bothwells depicted herein were cousins, though many times removed, to the Bothwells on Clyde.

Nathan Bothwell and his sons were respected operators of “Bothwell Marine Works”, a ship design and construction business which built ocean- going vessels until the decline of local grown lumber. The family interests then turned towards shipping and they became active as cargo masters and warehousemen for both coastwise and offshore traffic. They established a relationship with warehouses in the American colonies at Boston and New York.

Managing and supervising a large work force of skilled waterfront craftsmen required tact, diplomacy and the ability to confront every challenge and especially to the testing of their craft experience. William, Nathan’s second son, could hold his own at every challenge. Not so his elder brother Robert, who would rather handle the business end and entertain the customers. Robert, a born politician, was at his best when socializing and making up to political and government leaders. The Government had recently commissioned him master storekeeper for the Crown’s interests near the family facilities in Massachusetts.

Robert and his family sailed for the new world. William and his wife Mairi, the youngest brother Jonathan and their aging parents, Nathan and Mercy, remained behind to manage the family’s dwindling shipbuilding and foundry business. The decline of business was also blamed on competition with American ship-building, along with their unlimited supply of timber in the new world, whereas Clydebankers had to import their timber from the Colonies or the port of Riga on the Baltic.

Wars, severe weather, and importation had created hard economic times throughout Britain but were hardest felt in Scotland. Because of the lack of local grown timber or manufactured products, local new ship construction came to a standstill.

Despondent at watching the business decline and angered that brother Robert left when he was needed most, William was often found frequenting Keith’s Inn and Tavern. Many of the more skilled craftsmen who once worked at the Bothwell Marine Works would often stop in for a pint or two, hoping to approach William for a few hours of part time work. No work was to be found anywhere, not even for the most valued or skilled craftsmen. The families of these men were feeling the pinch, as any savings they had managed to collect were now being used for day to day living.

Only the foundry remained busy because the molders and pattern makers were some of the most talented artists in the marine field. Bothwell had recently developed a progressive pattern process for casting a moderate weight capstan that could use replacement parts, such as pawls and lignum-vitae bearing staves, and was becoming standard in the Royal Navy. Also developed was a new multi-stage bilge-pump that was capable of lifting bilge water from the very depths of a vessel through a series of clapper valves and leather sealed pistons which were operated by seamen pushing and pulling on a rocking lever action then discharging the water on deck. This proved to be much more efficient than the old bellows-like pumps.

Some of the idle workers would sit around speculating on the rumors that Prince Charles had already landed in Scotland. They spun yarns that soon became wild exaggerations of the Jacobite uprisings back in ’15….even though some of those exaggerated tales had only a slight ring of truth. Many of the men even discussed joining the ranks of the “Young Pretender” if an opportunity arose; they were that desperate.

William was suspicious that the French had a hand in spreading the rumors and this news only heaped more concern on the pile of troubles he already had.

The Bothwells were a family of proud Presbyterian Scots. They wanted a free Scotland, they hated the French, Robert was now doing service for the English Crown in the Colonies, and they were also somewhat sympathetic towards the Catholic Prince Charles’ claim to the English crown because mother Mercy’s family had deep roots in the Highlands………What a dilemma!

PROLOGUE

BATTLE OF CULLODEN

APRIL 16 1746

A cold wet morning with the promise of more rain to come and even a threat of sleet greeted the two armies who were about to face each other on this day in what, by late afternoon, would become the final and decisive engagement for the throne of England and Scotland.

The English battle lines were forming after much maneuvering and parade fanfare in cadence to each of the battalion’s drummers. Colors and standards were unfurled to flap wildly in the wind then planted at the head of each Regiment, identifying from whence they came or the officer in command. Artillery was pulled and pushed through the muddy quagmire into the forward lines by laboring groups of foot-soldiers sinking knee deep in the muck, their uniforms now covered with thick globs of mud.

Other soldiers were busy building up a berm in front of the cannons to protect the gunners from musket fire or an all out charge, while others of the gun crews were laying out the implements of ordinance to make ready for the command to “Fire”.

Once the Artillery piece was in place it took less than three minutes to clean the bore, load, aim and be ready to place their slow burning matches to the freshly primed touch-holes. Then, within an instant, a thunderous explosion would belch the weapons deadly shot toward the enemy’s ranks.

The muzzle explosions brought to life the purpose of the task ahead. The Clans began to feel the destructive forces of the cannon’s grapeshot as their front lines were decimated and warriors from the rear came up to fill the voids in their ranks. The withering bombardment continued unmercifully until a thick cloud of burnt gunpowder with an acrid stench slowly drifted over friend and foe alike, obliterating all vision of the enemy’s ranks.

And then a moment of eerie silence interrupted only by the occasional feeble report from the Clan’s battery of antique weapons and ill trained gun crews. They too fell silent when it became obvious of their ineffectual fire.

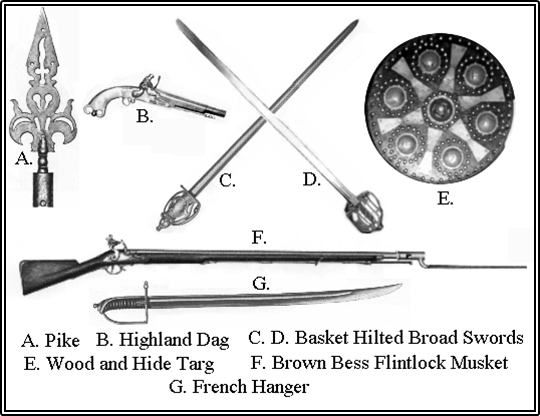

The clans began chanting in unison, “CLAYMORE…CLAYMORE” as they beat their swords on their targs, made of wood and bull hide, begging their leaders for the order to advance…. only to be held in check by their commanders who were themselves awaiting orders from a higher authority.

The angry sounds of the Jacobite taunts were heard over the Moor and continued until their gut-retching yells reached a crescendo that every English soldier recognized as a precursor to their attack. The screeching and bleating of the pipes and the rhythmical beatings of drums were whipping the Clans into a frenzy, but they held their line. Until….the men in the forward ranks of Clan Chattan spotted the banners and kilt attire of their blood enemy the Campbells of Argyll, who were fighting on the side of the English Crown and were inching their way behind a wall of stones trying to flank the Jacobite lines on the right.

Clan Chattan was a mixture of small Clans from many of the Central Highland Glens around Loch Ness and as far south as Loch Lomond. They made up the attacking force now in hot pursuit of the Campbells of the Argyll Militia.

By now the hail of English musket fire was finding its targets; men wearing the blue bonnets with white cockade and thistles were falling all about. Men of the Clans MacGregor, Mackintosh and Cameron suddenly burst from their ranks and charged across the moor in such frenzy as to overwhelm the front lines of the English, sending them into a near rout.

Heavy smoke from the recent barrage lay just a few feet off the mire obliterating any view of the combatants.

“We’ve got ’em on the run lads, keep after ’em!”

A retreating column of English redcoats suddenly stopped, turned, and fired a final volley. Then, seeing that their situation was seemingly hopeless, they threw down their muskets and ran.

The chase was on, the enemy was in full retreat across the green, stumbling through the wasteland of craggy rocks and down into the bogs at the low land area of Culloden Moor with the Scottish Irregulars on their tails in hot pursuit.

Suddenly the enemy vanished over a rise and the only army in sight was the Scots clambering over the rocks and who, as yet, hadn’t reached the bog.

A command was sounded, “Fall back! It’s a trap!” The horns and pipes were calling them back. The advanced brigade of several hundred Highlanders suddenly became isolated from the main body as they were encircled by redcoats; the English seemingly coming from nowhere.

Andrew MacCullough at Culloden

Wearing the White Cockade

A small tight knit band of men could be seen fighting hand-to-hand, with dagger and broadsword, forcing their way up the green trying to reach the ranks of the Scot reserves who were firing their weapons at the English as fast as they could reload.

“Follow me lads! Stay together and we’ll fight our way out!” The towering figure of Andrew MacCullough loomed tall and proud as he led the small group of the trapped men up the green. Redcoats were charging from the high ground on all sides of the moor.

No fiercer battle ever took place as on that spring day at Culloden Moor in 1746. It was a battle that broke the spirit of the Scottish Patriots and succeeded in silencing their demands for a separate Scotland forever.

Andrew MacCullough, a heroic leader to all about him, nearly reached the safety of his own lines and was still encouraging his band along when a musket shot fell the giant redhead.

Jonathan came upon his fallen uncle and tried to comfort him.

“Here….Jonathan…” MacCullough gasped, a short breath rasping between each word… “take my sword….I fear I’ve been mortally wounded….see that your mother gets my….augh.” The blood poured from his mouth with his last tortured cry and Andrew MacCullough slipped into the hereafter.

“Uncle Andrew….Try….We can make it. Don’t give up! We can carry you.” With tears swelling in his eyes Jonathan cradled the upper body of this giant of a man in his arms.

An aide to the Clan leader yelled “Give it up m’ lad can’t you see the brave man’s gone? Take the Tartan and his sword so the bloody buggers can’t lay claim to the bounty on his head.” At that moment another deafening volley of musket fire sounded just beyond the moor as the enemy advanced up the green towards them.

Jonathan removed the sword from Andrew’s out-flung hand and unbuckled the scabbard and, though it pained him to remove the Tartan, his uncle’s pride, he knew he must. For if the Clan MacCullough Tartan should fall into the hands of the English a price would be on the head of every male MacCullough ’til there were none left.

A shout from a kilted Highlander was heard over the sounds of battle. “Run for your lives, they’re trying to ring us again!”

As he stood clutching Andrew’s blood-spattered Tartan and treasured sword, Jonathan’s shoulder and back exploded in burning agony and the left side of his body numbed with pain. He stumbled once as he looked back at the body of his fallen Uncle, then picked up the pace to join the others fleeing that desolate moor and the brave men who died in that most wretched of all Scotland’s battles.

For the hundreds of brave Highlanders slain that day a coronach and cry was heard in every glen and mountain stronghold and the likes of Andrew McCall (nee MacCullough) will forever be remembered.

THE FIERY CROSS

GLEN LYON – 1745

Jonathan Bothwell, his lady friend Elizabeth MacAllister (Tibby as she was affectionately called) and her four brothers were preparing for a journey to the annual MacAllister family’s reunion at MacAllister Hall near Glen Lyon in the central highlands.

Jonathan had been invited to join them to meet the whole family and, maybe, begin the traditional negotiations on the custom of a dowry. The brothers, all but one being older than Jonathan and being very protective of their baby sister, encouraged him to partake in many of their activities so they could keep a watchful eye over him.

It was obvious the brothers approved of Jonathan and knew that they could convince the family to agree to the marriage. The brothers and Tibby had been staying in town with their mother’s brother where Tibby kept house and the boys, on occasion, worked for Bothwell Marine Works and therefore knew somewhat of Jonathan’s family background.

Unfortunately, upon reaching MacAllister hall, marriage was never put on the agenda; much more important issues were to be considered first. A call to arms order, by way of the Fiery Cross, was received by the MacAllister Clan. They were expected to send representatives to a Heraldic meeting….No exceptions.

Tibby’s brothers and other male members of the family departed immediately for the gathering. They were gone for a night and a day and on their return a solemn and secretive pall overtook the large family gathering of some one hundred people.

As soon as the horses were cared for and stabled and the men were fed, a meeting was called in the great room of the main house. Jonathan, because he wasn’t blood family, was asked to retire to an out-building with some of the other house guests and farm laborers. The out-building was built of stones and mortar similar to the great house. No doubt that this had served as the great house in the past until the other was built. Most of the floor around the fireplace was stone with some wood in the outer edges of the very large room. The peaked roof with missing pieces of slate had been thatched over and seemed to keep out the cold wind but Jonathan wondered if it would keep things dry in a heavy rain.

Even over the cold and howling winds they could hear occasional shouts of rage coming from the great house…. then angry screaming and sounds of a brawl so loud it would seem all the Clan men were involved. This was a very strange turn of events and the non-family members with Jonathan puzzled over the Clan’s odd behavior and couldn’t imagine what was going on.

“What do you make of all of this?” Jonathan asked a fellow who had his nose pressed hard against the window.

“Could be that some kin died or some disaster in the Burgh, but then they would have needed us,” he replied without turning his head away from the glass.

“I heard something about a Fiery Cross….” Before Jonathan could get out another word he was interrupted.

A tall old gent that answered to the name of MacTavish stood in the rear of the group at the window. “Fiery Cross, did ya say? You all know what that means. Lord, help us!”

A wife of one of the laborers from the lowlands asked what it was all about, as she had heard tales of the Fiery Cross but wasn’t sure of its exact meaning.

“It means war and I’m not going to get caught up in it. The rumors of Bonnie Prince Charlie coming must have been the truth,” said MacTavish.

That still didn’t answer the old woman’s question and she repeated, “What does the Fiery Cross Mean?”

“It’s two pieces of charred wood shaped like an X, just like the cross that our beloved Saint Andrew was crucified on. You tie it together with a sample of Tartan from a Chieftain of the Highland Clans, along with a personal token, proving it’s authority and known only to the family receiving the Fiery Cross. Then it’s either placed on the door stoop or actually thrown at the door by some secret messenger. It’s a traditional call to arms. I still don’t want any part of it.” The lanky old gent turned away from the group and went to the fireplace and sat on the edge of the hearth.

Jonathan followed him wondering why this man was so upset when, to him, words like “Fiery Cross” and “Call to Arms” set his heart racing and his stomach churning with excitement.

“You know laddie, I’m too old for another battle. I’ve got the scars to prove my courage. Besides, things have changed. Once we warred over religion, then it was against the cruel Kings, then it was for Scotland, then it was for ….or….was it against the French. Half my family lives in Ireland under an Irish name. My daughter ran off and married a Lowland Presbyterian. You young lads will go off to do battle and half of you will not come home and all for what….?” He stopped, cradled his head in his hands with his elbows resting on his knees. “I’m na’ a coward….We need our strong young lads to work the soil and tend the farms and raise families, not going off shedding their blood.”

The reasoning outbreak of the old gent so humbled Jonathan that he was almost put to tears. He went to the distraught man and laid a hand on his shoulder then glanced about the room. All eyes were on this gent by the fire and no one spoke a word for a very long time.

Morning came, the passing storm cleared out the clouds but lowered the temperature to near freezing. As the sun rose, smoke from the chimney fires hovered low overhead.

The hill across from the farm was crisscrossed with stone walls three to four feet high and several feet across, dividing the hill into large plots of different colored patches. Not a tree was to be seen on that hill or any of the hills nearby. Only a few stumps, here and there, were all that remained from heavy timber cutting in the past, and this had once been the center of the Great Caledonian Forrest.

People were now coming out of the great house, loading the carts with their belongings and hitching up the animals preparing to leave. Some hugged, others abruptly turned away. Tears were everywhere, as nearly half the clan prepared to leave, departing in every direction.

A few of the people, on leaving, waved towards Jonathan. He couldn’t understand what had happened to the mood of this large gathering which only a short time earlier had been a happy and friendly group of relatives….now changed into an angry congregation leaving the estate.

Not willing just to stand idly by, Jonathan burst into the house and confronted the brothers for an explanation.

“What in blazes is going on?” he demanded, “Why is everyone leaving?”

Two of the younger brothers who were most friendly with Jonathan ushered him out of the house and started walking out towards the fields as one excitedly explained, “Do you remember the story we told you about our clan and how it once fought in the battles along side of James II? Well, we’ve been called on to form a company of fighting men to join in a similar cause. Our own Bonnie Prince Charlie, grandson of James II, is calling all who are loyal to the Stuarts. It’s possible….just possible….that while England is distracted by uprisings in Wales, trouble with the Indians and the French in the Colonies and the Crown’s interference against France over Austria we can rid Scotland of her bloody rule forever!

“Because of your older brother’s connection with the Crown, keep a closed mouth when we get you back to your home, for Duncan here,” he clapped his younger brother around the shoulders, “and I will be joining our two older brothers in recruiting men to fight for our Bonnie Prince. Tibby and the three of us will start back for Dumbarton today. By the way, forget any thoughts of a dowry until this is over.”

A dowry and, he was ashamed to admit, Tibby herself were the last things on Jonathan’s mind at present. Excited again now, he bombarded the brothers with questions of “When…Where…How?”

“Enough, lad, enough!” the older boy said. “It’s not your problem as yet! Your Pa will be boxin’ our ears for filling your head with as much as we have!” They turned and started back to the great house to say their goodbyes and prepare for the long journey home.

UNCLE ANDREW McCALL

Nee

MacCullough

Nathan Bothwell purchased the house from the heirs of a banned Jacobite family after the turn of the century. He thought it ideal because of its location close to the Marine industries on the Clyde and that it was able to accommodate a large family.

The Bothwell Estate

The house, made from large cut stone blocks, was two stories high and had a castle-like rook overlooking the Firth of Clyde, a short distance beyond. Bothwell was considered a small estate by most comparisons of the region. The town of Dumbarton was a few miles down the Clyde from Clydebank.

Tibby and her two youngest brothers, Neil and Duncan, returned to the estate with Jonathan and were invited to stay at the house until the older brothers and their Uncle returned from their travels. The true story of the older boys and their uncle joining Bonnie Prince Charlie’s supporters was kept from Nathan. He was told that they were away to purchase animals for the farm.

The men were sitting at the table sipping their port after the large supper that Mercy Bothwell had insisted on helping the cook prepare. The women, Mercy, William’s wife Mairi, and Tibby, were preparing rooms and beds for the guests.

“You’re home sooner than expected,” Nathan remarked to his youngest son, “How did it go up at Glen Lyon?” Not waiting for an answer he then announced, “We received word from your brother Robert in America just this morning. Everything is going very successful for him. Government shipping is increasing due to outbreaks with Indians in the Colonies and the need for more warehousing is growing. Robert even suggested that if business at the Works stays slow after winter, it might be wise to consider moving everything to the Colonies.”

As Nathan read on, he directed a passage of the letter to William, in which Robert indicated that he had very little money to send home because the need to enlarge operations at Boston was taking almost all of the profits to finance the expansion.

William was used to Robert’s flair of superiority and his dreams of someday becoming master of Bothwell; he sighed and looked at his father. “What in bloody hell does he intend to do with our holdings here….not to mention the family home…. if we were to move to the Colonies?”

He slammed the flat of his hand on the table, almost upsetting his glass. “Would he sell everything here on the chance of becoming rich at the whim of the English King?”

Jonathan traded furtive glances with Neil and Duncan as his brother raged.

As Nathan poured more port in his glass he silently sympathized with his son. Nothing could change the fact that William was born the second son and was therefore relegated to be subservient to his older brother.

Nathan glanced at his youngest son and thought, “Poor Jonathan, he gets nothing but the tail.” Then, to change the subject he told Jonathan and the MacAllisters about the assemblage of business owners, shopkeepers, neighbors and friends that had met the previous night at the church to discuss the troubling times of poor business, problems with France, Wales and Charles Stuart’s “Call to Arms”.

“We don’t know what effect these things will have on businesses along the Clyde,” he said, “Opinions ran high and were about evenly divided…..nothing was accomplished.”

“It seems that it’s no secret that Prince Charles is here,” Nathan continued, “but when will he show his force and who will support him?”

“I’ll support him sir,” snapped Tibby’s youngest brother Duncan.

“And I!” responded his brother Neil.

A pounding on the window startled everyone and then heavier pounding at the door brought the women downstairs.

“Get the door Jonathan!” Nathan said, as he rose from his chair.

Jonathan opened the door and stepped back a pace as a large red-bearded rough looking beast of a man loomed in the door way.

“Where’s my little sister Mercy?” demanded the intruder… “Nathan, you cagy old codger how be you?”

Then he turned to the frail lady at Nathan’s side, “Mercy m’love, don’t you recognize me? It’s me….Andy….do I look that bad? Come, give us a big hug.”

Everyone stood dumbfounded; no one could speak, even Mercy was at a loss for words, looking as if she had seen a ghost.

“You must be Uncle Andy. I remember seeing you ten or twelve years ago,” said William. “Mother, don’t you recognize him?”

“I do…I do. He just took me by surprise, like a ghost from the past. Sure I recognize you! Give me a hug you big hairy monster! You must be freezing. Here, have a toddy and let me fix you some food.” Mercy embraced the huge man, pushing him towards a stool in front of the crackling fire.

“I’ve been traveling out in the cold for days! Let me get next to that fire young fellow and shut that damned door.”

“I’m Jonathan your nephew. Glad to meet you sir. Mother has told us about you. Have you traveled far?” The young lad eagerly offered his hand.

“I guess we’d all like to know,” Nathan said, “the last time I remember you passing through was about twelve years ago. You were on the run with the King’s men hot on your tail.”

“How’s the family Andy….The wife….besides your sons, didn’t you have some daughters? What’s been happening?” Mercy fixed him a plate loaded with pieces of beef, cheese, bread and preserves and then filled a mug with a hot steaming liquid.

“Mercy, you still ask too damned many questions,” the giant growled. Then, turning to Nathan asked, “How do you put up with her?” The big man paused, looked about the room and with his mouth crammed with food blurted, “Nathan, kindly introduce me around. I must know who I’m confiding in; it could mean my head you see.”

“You know William, and this is his wife Mairi,” Nathan said as Andy engulfed Mairi’s hand with one huge rough paw and patted it with the other.

“You’ve just met my youngest, Jonathan, this is his lady friend Elizabeth,” Nathan always insisted on using her full Christian name, “and her two brothers Neil and Duncan MacAllister. My oldest son Robert is in America with his family. Now, about yourself, we’re all family or soon will be.”

Andy looked closely at Neil and Duncan. “By some chance are you lads from the central Highlands around Glen Lyon and that rascally Clan of Rufus MacAllister?” he asked.

“That would be my uncle Rufus,” Neil responded.

“Then I can trust everyone here but you Nathan…. no….I take that back. I know your leanings and I also know you are an honorable man. I’ve trusted you with my life before. Sorry I really don’t know why I said that.” He continued rambling, slurring his words, looking as if he was about to collapse.

“I’m on an important mission and I need help. I’m so tired…..if I could just get some rest I’ll be on my way….”

“Are you alone Andy? Is someone after you? Are you being chased? Andy please tell me,” Mercy pleaded.

“She never changes….questions….always questions,” he muttered. His empty plate dropped from his hand and he crumpled to the floor like a large sack of potatoes.

It took the effort of all the men in the house to haul the monstrous body of Andrew to the large leather settee in the library. They stood there studying the man. It was apparent that he couldn’t go any further and needed a safe haven. It was fortunate for him that he’d even made it this far.

“Da’, tell us what he was talking about,” demanded William. “Sounds like he was in trouble before and then you helped him.”

“Boys, I don’t know if this is the time to reveal the past but I can say this…. Andy and his brothers were a peaceful family at one time until their politics and religion got the better of them. How can I not help this man when I know for certain that if all Scots were as patriotic as he, Scotland would rule all of Britain.

“Your mother doesn’t fully approve of his activities. It’s not that she is not patriotic, but she feels others should shoulder some of his burden. She has seen four of her five brother’s fall while trying to keep the flames of their cause alive. He’s been living these past years in Ireland to escape the bounty placed on his head and changed his name from MacCullough to McCall to keep the King’s men from finding him. I needn’t caution you to keep this secret to yourselves.”

Nathan took one of the blankets that Mercy had fetched and pulled it over Andy’s sleeping frame. He winked at William and said. “That other blanket would do well over his head if he continues with those snores! Come, let’s see if we all can sleep as well as he tonight. It’s time to retire.”

Tibby and Jonathan stayed up after the others turned in trying to decide what to do about their future. They climbed the stairway to the rook tower and huddled close to share the blanket that protected them from the chilling wind….. As Jonathan looked down into Tibby’s adoring eyes he felt again the excitement that had been his almost constant companion since the news at MacAllister Hall had sent his blood boiling….only somehow this time it was different. He cupped her little chin in his fingers and lowered his mouth on hers…………

Mother Mercy always rose before the sun to start the day, seeing that her men folk were properly attired, fed and sent off to work. The cook usually came in between nine and ten and stayed ’till the baking and heavier work of supper was over. She could afford a housekeeper but enjoyed doing most of it herself. Besides, Mercy was a very private person.

“Get up and bathe you stinkin’ lout, I’ve got hot water on the fire. And get those filthy rags off now, so I can do something with them,” she nagged, half in jest just as she had done many years ago when she helped care for all her younger brothers, save Andrew, who was the eldest of the brood.

“Just like old times, eh Mers? God, how I sometimes long for those days.” Andy stretched and scratched as he worked his way to the pantry just off from the large fireplace where a large kettle, steam rising from the rapidly boiling water, rested on a black iron spider squatting over the hot coals. He pulled off his garments, which appeared not to have been washed in months.

“How long have you been away from home?” Mercy asked.

“I left Londonderry three weeks ago and have been on the move ever since, trying to catch up with the Prince.”

“How are your wife and children?” she asked as she bustled around the kitchen. “I’ve got porridge cooking. Have some tea.”

She drew a couple of buckets of water from the cistern pump at the back door and poured them into the large half-cask that served as their bathing tub, then topped it of with the boiling water from the fireplace.

“Your bath’s ready. I’ll ask again…..how is your family?”

“The two oldest went to the Carolinas, my youngest is with the Prince now, and my daughters all have large families. The wife is with our oldest daughter.” Andy stepped behind the curtain Mercy had draped between two high-backed chairs, dropped his clothes and climbed into the tub.

Nathan came into the kitchen and headed for the fat teapot sitting on the sideboard. “Good morning to you Andrew. I see Mercy has you well under her control. I don’t know what we would do without her always bossing us to take baths, change clothes and the like. I guess she had plenty of practice raising you boys.

“We went to a meeting the other night where the discussion of the war with France and your group’s uprising raged hot and heavy. Convince me to take the right path.” Nathan handed the bather a cup of tea.

Other members of the family began gathering near the warm fireplace getting their first cup of tea and pretending not to notice Uncle Andrew in the tub.

“I’m not used to an audience whilst I take m’ bath. Turn your heads!” Andy bellowed. The group turned around, snickering as they headed for the breakfast table.

“I’ll tell you Nathan, you’re the only man I have ever discussed both religion and politics with in the same conversation without the threat of mayhem. We know each other’s position, so why don’t we let it go at that for Mercy’s sake,” Andrew pleaded.

“You’re saying that nothing has changed in lo these many years to make you more considerate?” insisted Nathan.

“Damn me, Nathan! A true Scot is for Scotland. You should support the rightful Scottish heir to the English throne, be he Scot-Catholic or not!” Andy rose out of the tub, dripping and splashing water on the pantry floor.

“You’re giving Scotland to the French to kill our own blood kin. Think, man, before you destroy us all!” Nathan turned abruptly and left the pantry.

Mercy had gone from the cooking area before the conversation became strained. Tibby and Mairi took over preparing breakfast and began serving the table, all the while keeping their ears trained on the heated exchange.

“I’m a guest in your house and I’ll not say another word on the matter Nathan….Agreed?” Andrew was standing behind the curtain Mercy had strung so as not to embarrass anyone.

“Andy! Drape that curtain about you and go to the library. I’ve got your clothes all laid out,” Mercy snapped as she entered the kitchen, ignoring the arguing of the two men. “If you haven’t gained too much weight these clothes just might fit.”

Andy walked into the library and a few moments later he reappeared still wrapped in the curtain and in a most solemn manner asked, “Dear sister, would you mind trimming my hair and beard like you used to in the good old times?”

“Of course Andy, sit yourself down and I’ll make your appearance fit for a King.” Mercy smiled and pushed a stool towards him.

“I have an early appointment this morning and when it’s over I’ll come right home, love.” Nathan kissed Mercy on the forehead just as he had done for many years. He clasped Andy on the shoulder, said his goodbyes to all and left the house.

Mercy, her scissors flashing, trimmed and clipped Andy until he began looking more like a man than the huge bear that had invaded the house the night before. She made a final snip and then stood back admiring her handiwork. “Now off with ye….get dressed!” She gave him a playful push towards the library.

Twenty minutes later a gasp from Jonathan hushed the din of the breakfast chatter. The family sat in silent awe, staring.

A BLUE BONNET, WHITE COCKADE,

HIGHLAND THISTLE AND FEATHER OF A SEPT LEADER.

In the doorway stood the most magnificent figure of a warrior ever imagined. From the Bluebonnet adorned with a white cockade and the eagle feather of a sub-chief, to the kilt, hose and brogues, Andrew stood resplendent in his accoutrements such as the ornate gorget at his throat and basket-hilted Claymore sword hanging from the buckled, broad shouldered belt at his side. The forbidden Tartan kilt was drawn from behind the waist, under his right arm and up across his chest to his left shoulder, where it was gathered and secured with the large crested brooch of his clan. The Tartan was allowed to hang free down to his knees, imparting a stylish and cocky flair, and at his groin hung a beautiful furred sporran to carry his rations. Such splendor!

“You’ve made me feel like a man again Mers. I’ve never felt prouder in my life than when wearing the Kilt. I feel invincible. I feel like I can go into battle and win!”

William, Jonathan and Tibby’s two brothers stood in awe. The four young men had only heard of such beautiful uniforms. The English Crown had outlawed everything ….the Tartans, Bluebonnets such as this and, of course, the beautiful Bagpipes….many years ago.

“That’s all I have left of the old family, Andy dear. Do you remember when the British were hunting you after the defeat at Preston and Nathan hid you and provided a vessel to take you to Ireland? This is your old tuck that we hid from the searchers. Every time I take it out of the chest I hold it close and it brings back memories of you and your brothers, when we were all so young. Now….you young people….don’t let that uniform sway you. War is the plague of the world! Tell them Andy.” Mercy turned away knowing in her heart she opened old wounds.

“Is it true, that if we don’t fight to put Charles on the throne, Scotland will forever lose its rightful linage to the throne?” Jonathan eagerly questioned.

“Right you are lad,” answered Andy.

“I see a lot of what appears to be Frenchmen in the countryside. Are they going to fight for Scotland against the English and then leave Scotland when it’s all over? Or will we have to be subservient to them?” asked William.

“You’ve been listening to your father. I don’t agree with his reasoning but I’m not going to argue against him in his house. That would not be honorable. I’ll just say that the Highlanders have a lot of history that the English have taken away from us and we have to try and recover it now.”

With that, Andy walked out to the pantry area where Mercy was washing his old clothes. They conversed for an hour asking and answering each others inquiries until you’d think they would talk themselves out of words.

When Nathan returned home he was surprised to see Andrew in all his fine regalia. Even though he wasn’t comfortable that Andrew should display symbols not of his choosing, he didn’t comment on the matter until he learned that his dear wife had stored the uniform, under his nose and in his house for so many years.

“You’d think a man would know a woman after thirty or forty years,” he mumbled, “yet, there she stands, the Mother of my children….and I don’t know her at all!”

Turning to William he said, “And I suppose he’s been filling you and the other boy’s heads with tales of the glory of war!”

“No sir,” said William, “He refused to discuss the coming crisis unless you were present.”

“Enough of this bickering,” Andrew announced, “I’m going to leave after dark for the Highlands in search of Charles’ forces and I’ll be stopping at Rufus MacAllister’s headquarters. Anyone wishing to come is welcome!”

“We’re with you Andrew MacCullough!” said Neil and Duncan in almost the same breath “We had business to tend to here in Dumbarton, but it can best be handled by others.”

Jonathan looked at his father. The look on Nathan’s face cautioned Jonathan to hide his excitement. “I’ll go as far as MacAllister Hall and see that Tibby is settled in with her Mother.”

He glanced again at Nathan, “Once she’s safe, I promise to return.”

Mother Mercy was already preparing haggis for dinner and oat porridge bricks for the Highland journey.

******

The ensuing months brought no direct word from any of the departed family members, only reports of clashes from as far down into England as Derby, just a few days travel from London. Then, days later, reports had the Jacobites back up in Scotland battling at Stirling.

Nathan and Mercy were at their wit’s end fearing that Jonathan might be caught up in the fighting when he hadn’t returned as promised.

William thought the fighting must be spreading through out the country or armies of men were traveling great distances very quickly.

The feeling of most people around the Clyde was hurrah for Prince Charles as long as he was triumphant. But many felt that he failed to arouse enough enthusiastic support from the population centers around Glasgow and that he should have made overtures to Presbyterian notables to attempt to restore their Scot patriotism. Without support of the Protestants he was sure to lose his following.

Word spread that a great battle had taken place at Culloden Moor just a short distance from Inverness. Further reports indicated that it was a total defeat for the Highlanders and that the English were in hot pursuit of anyone who may have participated in the general uprising.

British troops were seen coming over the back country from the direction of Stirling towards Dumbarton on the Clyde. Other reports had them coming down the west banks of Loch Lomond from the Grampians and converging on Dumbarton from the west. At the same time vessels of every type and description were assembling to carry the British troops south to engage the French; or so the Scots hoped.

It was early morning when a contingent of British troops entered Dumbarton. William had left for the foundry and Mairi had taken a horse and carriage to Tibby’s Uncle’s house. Despite the danger of traveling the roads during this fearful time Tibby had made the long trip from the MacAllister estate by herself. She had been in town with her Uncle for two days and Mercy and Mairi were curious to find out the reason for her return. Perhaps she had word of Jonathan’s whereabouts.

Highland Weapons

AFTER THE BATTLE

“ALL THE BROTHERS ARE GONE”

A tall elderly man stepped from behind a shed at the foundry and blocked Williams’s path. “Are you William Bothwell, brother to Jonathan?” He waited for an answer.

“Why do you ask?” William demanded.

“Are you, or are you not, Jonathan’s brother?” the old man asked again.

Fearing it might be some sort of an English trap; William was unwilling to reply to any more questions and continued to walk towards the mold shop.

“He’ll not make it through many more nights. Andrew and the MacAllister brothers were lost at Culloden.” He hesitated, noting the pain that twisted William’s face, then continued, “Jonathan was hit in his neck and shoulder and infection has taken over the wounds. We’re sore afraid of losing him and others we have in hiding.

“Now will you come?” he pleaded, “I’ll take you to him. It’s more than a two day’s ride and we’ll have to dodge the bloody heathens.”

“You follow me,” William said, after weighing his alternatives. “We’ll go by my house and get a few things. But, whatever you do, watch your words to my parents. They’re old…..and my mother has a bad heart. We can start from there after you’re fed. You look like you could use a meal.”

“By what name are you known?” asked William as he saddled his horse. The old man had gone behind the shed and walked out an old sway-backed nag, lathered from hard riding.

“MacTavish,” he replied, “Not enough of us around anymore to waste using Christian names.”

The road from the Clydebank to Dumbarton was teeming with people, their animals over-loaded with household belongings, many toting large bundles on their backs. Some were coming from Dumbarton and some seemed hurrying towards the city, indicating to William that the British military had infiltrated the entire area.

“Come,” William said, “we’ll make no time fighting this mob on the road. We can travel faster through the fields and over that yonder hill.”

They approached the Bothwell estate cautiously, observing a company of light horsemen leaving with arm-loads of booty that William recognized as coming from his house. They hid behind a heath row until the soldiers passed and overheard one horseman shout to a man evidently left to guard the house. “I’ll alert the Lieutenant and be back at sundown. It looks like a good place to camp. Get rid of the bodies….and if I find you’ve emptied the wine cellar, there’ll be hell to pay! Guard those ship instruments well. Maybe I can make my Sergeant’s stripes if Lieutenant Gordon is in a receiving mood!” The soldier laughed, kicked his horse, and galloped after the retreating men.

William tried not to think about the chilling words tossed out so casually by the soldier. Approaching his home cautiously, he and MacTavish got down from their mounts, tethered them behind one of the out-buildings and walked the last several hundred feet.

Through an open window they saw the sentry roaming through the house. He was oblivious to anything outside as he opened cupboards and drawers and scattered their contents in search of valuables.

When they saw him move from the great room towards the library the two men silently opened the back door and crept into the pantry. William froze in horror. The sight of his parents crumpled on the floor made him forget the soldier and he bellowed in rage.

The soldier ran back into the pantry, his bayonet ready to attack. At the sight of the soldier William picked up a chair and smashed the weapon from the man’s hands. Then he charged the man with his bare hands; punching, choking and kicking until there was no sign of life.

Gasping for breath, he returned to where his parents had fallen. MacTavish, seeing the old man stir, had lifted him off of Mercy and propped him up with a cushion. Nathan seemed to be coming around but it was obvious he was critically hurt. William knelt next to Mercy, but saw that nothing could be done for his mother; her heart must have just given up.

William moaned and gently closed Mercy’s eyes. “English bastards!” he screamed.

Rising from Mercy’s side, William glanced over at MacTavish, “There, man, in the bottom of that cupboard, you’ll find a ‘glass. Go up and keep a keen eye for the pigs. No doubt they’ll be coming back soon.

Dropping to his knees beside his father, William took Nathan’s hand in his. “They….wanted to know….where you lads were….they must think you…we….are Jacobites.” Growing very short of breath, the old man asked in a barely audible whisper, “How’s my Mercy?” William only shook his head.

Nathan, accepting the truth he dreaded to hear, closed his eyes and with a deep sigh, slipped away.

Trying not to think about his mother and father, but concerned with what his father had said, William started gathering any important family papers, letters or documents that bore the Bothwell name and tossed them into the blazing fireplace. He knew now, without a doubt, which side the English considered the family to be on. Nothing must be found that would connect the warriors at Culloden to William himself or to Robert Bothwell in the Americas, Master Storekeeper for the King.

A call came from above, “Mr. William, there’s a light carriage coming up the back trail with two ladies. I can see Tibby but I don’t recognize the other woman. What shall we do?”

“It must be my wife with Tibby MacAllister. Run out and stop them. Tell them to hurry to Cousin Fiona’s house and stay there until we come. Under no circumstances let them come in or indicate to them what’s happened.”

William stoked the coal in the fireplace to ignite as much of it as he could. Removing the uniform of the dead sentry, he stripped and dressed the body in his clothes and shoes. He then knelt at Nathan’s side and gently removed his ring with the family crest, then slipped it on the finger of the dead Englishman. Then he took an old flintlock pistol that was kept loaded above the mantel, fired a ball into the head of the dead soldier, and placed the pistol in the man’s hand. The red coat, white breeches and boots were tossed into the raging fire and stoked until there was no trace left of them. With any luck, William reasoned, when the marauders returned they would suppose the third body, if any traces remained from the fire he intended to set, to be William himself. William then ran upstairs to his room and dressed quickly for travel.

William loaded the soldier’s horse with odds and ends of household items. Then, leaving a trail of valuables as if being carted by a greedy and over-burdened thief, he led the mount to a stand of trees. William unloaded the loot and half-buried it, then removed the tack and chased the horse off.

He returned to the house and with hurt in his chest and tears in his eyes, William doused the bodies of his beloved mother and father and the English soldier with lamp oil. He sprinkled the rest of the liquid to other areas of the house then shoveled the glowing embers of coal about the once beautiful home, setting it full ablaze.

He grabbed the strong box, which he had removed from its hiding place, and bolted from the house. Transferring the contents of the box to his traveling case, he left the box open with some valuables scattered nearby giving the impression that the guard might have absconded with the loot.

Two miles up the back trail they paused and looked back at a column of smoke rising from the flames engulfing the once proud house of the Bothwells.

Cousin Fiona saw the two horsemen coming through the pasture and alerted her husband to take them and their mounts to the barn. She was carrying out food and blankets for the whole group. She offered fresh horses only if they would all ride out that very night and promise not to leave any trail or trace behind.

“The whole world has gone crazy and we don’t want any part of it. I’m afraid to house my own cousin for a night for fear they’ll swoop down and kill us all,” Fiona whined. “Please go away!” She turned on her heels went towards the house without even looking back.

Mairi ran up to her husband and put her arms around him sobbing, “What’s the world coming to? Why are we being treated like this? We’ve done nothing wrong. We’ve stayed out of the politics.”

William groaned and let out a long sigh, “I have such bad news for you Mairi, my love. Those English bastards murdered mother and father and the Bothwell home is burned to the ground. Now, we must leave everything we know and follow this man, MacTavish, up into the hills. Mairi buried her face in Williams shoulder and shook as she wept.

An anguished William turned to MacTavish and appealed, “They’ve killed my father and mother for a few pieces of silver and a cause too complicated for a common man to understand. Do you understand, man? Do you know the rights and wrongs committed in the name of the King, or England, or Scotland…or even in the name of God?” MacTavish didn’t answer, as he knew an answer was not expected.

William held Mairi in one arm and encircled Tibby with the other, “Come here Tibby. I want to tell you first. The Clan MacAllister is no more. They all fell in battle, as did Uncle Andrew. Your four brothers died like the heroes they were.”

MacTavish tugged on William’s arm, “Mr. William we’ve got no time to dally I don’t know how much longer Jonathan can last.”

Tibby, who had paled and sagged at the news of her brothers, started screaming, “No. no. no….it can’t be so….Oh most merciful Father please don’t take him from me also. Oh God…Oh God….Oh God.” It seemed to take forever for her to sink to her knees where she knelt, keening as she rocked to and fro…back and forth.

Mairi took her in her arms and tried to comfort her but there was no consoling the stricken girl. Nothing could be said to calm this poor young lass who had just been told that all whom she held so dear to her heart were dead or dying.

William turned to Tibby, took her from Mairi’s arms and gently stood her up on her feet. “Take hold of yourself, lass. I’ve found my mother dead and watched my father die! Then, with my bare hands had to kill a soldier and burn my family’s home. Now I learn that my Uncle is dead and my youngest brother is about to die. You’re not alone in your grief!”

“But….you don’t understand….I’m….I’m carrying Jonathan’s child. Oh dear God what am I going to do?” Tibby sobbed and turned pleadingly to Mairi.

William’s shoulders slumped and his head dropped, “When will it end,” he whispered, “when…will…it all…end!” Turning to MacTavish he said, “Come, man, let’s be off to the house to see about the horses.”

The men walked from the barn up to Cousin Fiona’s house and William offered to buy extra mounts, explaining that his carriage horses would not do for riding over rough terrain and that with good mounts they could get underway as soon as that very evening.

“Anything to be rid of ya William. Uncle Nathan was always good to us but with him killed by the Crown, what would they do to my family if they found you here?” Fiona’s eyes were everywhere but looking at William and she nervously twisted a corner of her apron.

“I guess I understand….” William hesitated and then asked, “Cousin Fiona, what if I should send a young lady to you that is with my brother’s child. Would you consider helping her until she delivers? I’ll make it worth your while.”

“When’s she due?” Fiona snapped… all business now.

“She’s due in two or three months at the most. Will you please take them in on their return from seeing to Jonathan?” “I’ll have Mairi stay and help. They’ll be no trouble.”

“We could surely use the money. I’ll do it… but only if you promise not to come around,” she replied.

Fiona turned to her husband, “Kelvin, you take their horses to the barn and see what you can do for riding mounts. Give that gentle little filly to Tibby, she’s not well.”

As William followed Kelvin to help round up the horses, he was thinking how he had never felt comfortable with Fiona’s husband; the man had never spoken ten words to him in all the years he had known him.

“I hear the English are offering money to tell where the Jacobites are hiding,” Kelvin muttered, “Fiona’s worried a neighbor might report you coming.”

Well, that made thirty words in as many years, William thought. And what unsettling words they were…he certainly hoped their little party had arrived unseen and that Mairi and Tibby could return unnoticed.

******

The journey to the Highlands where Jonathan and other survivors of the battle were hiding was fraught with fear. At every turn of the trail the party stopped to scour the country ahead making sure there was no enemy laying in wait.

Old MacTavish led the party. He would ride far up the trail then signal to come ahead when all was clear, leading them through valleys of rocky crags and up mountain slopes that both horse and rider had trouble negotiating. After two full days MacTavish led them near a large group of boulders and told them to stop. From somewhere amongst the huge rocks a strange voice demanded that they all dismount.

“It’s MacTavish, lad. I’ve brung Jonathan’s wife and brother. Take them to him and I’ll hide the animals.”

As the old man grabbed the reins and led the horses down the slope for safe hiding, a man scrambled down from the rocks and motioned for the group to follow.

As he walked up to the entrance of a well concealed cave, the man escorting them commented, “We have four badly wounded, including Jonathan, and seven of us are recovering. We lost three in the last four days. All the healthy men moved on to other places of hiding. No one dares go home again. There’s Jonathan over there,” he said, holding his candle high and pointing to what appeared to be an unrecognizable clump of rags against the cave wall.

Tibby rushed to the motionless mound, knelt, and gently cradled Jonathan’s head in her arms. She started wiping his perspiring face with her skirt, then gently kissing his brow and running her fingers through his hair. Jonathan seemed to respond ever so slightly.

“He’s in very bad shape. How he’s hung on this long we can’t figure,” said the escort.

“Do you have any drinking water?” William questioned.

“Water’s about all we have left. We were hoping you’d bring some vittles with you.” The man went to the entrance of the cave and brought back a bucket of water.

William took several cakes of porridge from his bag and exchanged them for the water bucket which he sat down next to Tibby.

Tibby tore a strip from her petticoat and she and Mairi started gently cleaning Jonathan’s face and neck area. The dried blood had mixed with dirt so that they couldn’t tell where the wound was until they started cleaning Jonathan’s back and shoulder and found the festering mass rising behind his left shoulder.

“Willy….I told da’ a lie about coming right back home….ask him to forgive me…. Uncle Andrew…. He treated me like his own son….like a man….I took his name for my own to protect our family’s name and I held him in my arms and watched him die. Will….it was so horrible….all the brothers gone.” Jonathan’s words were slurred and his eyes darted around the cave as he drifted in and out of consciousness; unaware the women were cleaning him up and changing the filthy dressings.

Finally, Jonathan stirred, opened his eyes and for a moment seemed aware of his surroundings; his eyes fell on Tibby and a hint of a smile touched his lips, “I love you sweet lady.”

“You have to get well so you can raise our son.” Tibby turned away so he wouldn’t see the tears streaming down her face. Whether he heard her words, only he knew. His will to stay alive had served its purpose and no more fight was left in him.

The men carried the body out of the cave and down the slope where several fresh mounds were barely visible. William and MacTavish laboriously picked and dug through rock and stone, trying to dig deep enough to bury young Jonathan.

As the men spent hours attempting to dig deep enough through the rocky terrain for a suitable grave, William questioned the tall man as to where his interest lay in all this. “Why are you so involved, Mister MacTavish? I’ve never met or heard of you before; you seem so deeply concerned for our welfare.”

“I’ve been a smithy for the MacAllisters nigh on to forty years. Clan chief Rufus and I fought side by side in many battles until I just gave out. Now with all the sons gone some one has to care for Tibby MacAllister. Besides, Jonathan and I became good friends.”

The tall leader of the group walked up to William and handed him a wrapped bundle, “These trappings belong to your family. Jonathan made a promise to come back and haunt us if we didn’t give them to you,” he remarked. “It seemed so important to him that you get the sword and other gear.”

As William took the large battle sword and drew it partially from its scabbard he saw the inscription ‘Clan MacCullough Semper Vivus’ with crosses of Saint Andrew engraved at each end. He sighed and shook his head as he assimilated the Latin phrase, “Clan MacCullough lives forever.”

“Maybe you can suggest a good hiding place for this gear,” William said to MacTavish, pointing to the Tartan and Sword.

The old man shrugged and looked at the hole they had just finished. “Why not let Jonathan take it with him to his grave.”

William laid the gear at the bottom of the shallow hole and together they lowered the body on top of the traps, then covered all and scattered the surface around the grave to appear as if the ground had never been disturbed.

“MacTavish, will you take the ladies down to Cousin Fiona’s place?” William said as they finished, “I’ll travel with you for a way then come back here, as my face is neither welcome nor safe there. I’ll give you some money for my cousin and for you to purchase and bring back what supplies you can. You know what is needed here.”

While waiting for MacTavish to return, William assisted in tending to the needs of the remaining injured men, cauterizing the infected areas and sewing up the punctures and cuts. William’s horse was slaughtered, some distance from the cave, for the meat. The bones and hide were buried to conceal any sign of human existence in the area. He hated to give the animal up, but if the English bush-beaters saw the animal in hiding it would be a dead giveaway. Now the group only hoped the weather would continue to stay cold and damp to make it miserable for the hunters. On the other hand, too heavy a downpour would force them, by the rush of cascading water, from this cavern carved out of the stone mountain.

They all feared that if someone left the cave and was captured that that person might be tortured into telling of its location. Therefore everyone agreed to stay until all were well enough to travel on their own…or dead.

The long hours of waiting gave William time to ponder and think of what his next move was to be. He hated to leave Mairi alone, but he knew she would be safer with Cousin Fiona than traveling with him. He was seriously thinking of making the journey to Ireland to hide, as many Scots had before him, until the world returned to a sense of normality.

One of the survivors who claimed he stood with the Camerons of Loch Eil in battle, told of his trek down from the defeat by way of Deeside. He had hopes of making it through Tayside to the west coast but the English were beating the bushes in every Glen north of Stirling…..and he had seen starving half-naked men and women coming out of their hovels to surrender to the troops, only to be put to the sword where they stood. He narrowly escaped capture only because of the coming darkness of nightfall. He made his way to this area near Glen Lyon on the journey to his home near Loch Eil some one hundred miles away.

This information regarding the route to the ports of Aberdeen or Dundee dashed any hopes William might have entertained to sail from there. He was positive he was being hunted and that a price had been placed on his head….just as surely as if he himself had fought along side the Prince at Culloden.

“What are the chances of going to the western shores?” he asked of the Scotsman from Loch Eil.

“Depends…..if you are of a Highland Clan and speak the Irish tongue then you’ve only got two enemies searching for you, the English dogs and the Argyll Campbells. Otherwise, the whole world is after the reward for bringing in a suspected Jacobite.” As the stranger from Loch Eil spoke, William guessed that the man was about the same age as he, and was as tall but a bit huskier.

The lack of the Scot brogue that was so typical of Highlanders conversing in English made William think that this man was well educated. There was also something about him that implied a military discipline, his posture, his ability to have others follow his suggestions.

The Loch Eil man continued, “I heard tell that the Government is paying five shillings for every Jacobite head brought into their camps. The bounty hunters care not whose head they take….even some of the heads of their own family are sold for the coin they can bring to line the pockets of those despicable blackguards! After all, the heads can’t talk to dispute the claims.”

“What is your name stranger?” William asked, “You speak the King’s English as well as the King himself and I noticed you also speak Gaelic to the others.”

“It would be better if we used no names, to keep at bay anyone with a thought of blackmail or reward. I know you to be the brother of Jonathan MacCullough so I know of your loyalties but I know nothing of the others.” In a hushed tone he confided to William that he had attended the University at Dunedin and the Academy de Geneva studying letters and Religion.

MacTavish returned in three days with most of the supplies but complained that the army was taking every thing they could lay their hands on. He also brought William back a letter from Mairi indicating that “things” would be tolerable and for him not to worry. Tibby, Aunt Fiona and she would get along nicely, as they intended to keep a very low profile.

Certainly, Cousin Fiona would not publicize the fact that they were staying on the farm. They were in dire fear for their lives but the soldiers roaming the area had been more content, at least for the present, to plunder the city homes and businesses than small back-country farms where there was little chance for personal “pocket” treasures.

MacTavish said that he wanted to drift back towards the MacAllister place and see if he could salvage any of his smithy tools. He confided to William that he wasn’t sure of the reception he would get when he arrived.

Many of the nephews couldn’t understand why their uncle Rufus MacAllister did not himself go to support the prince at the final battle but ordered all of his sons and all of their sons to show up on the battle lines alongside the prince. This almost caused a revolt at the family’s spring tithe gathering. Rufus’s reasoning was that should the English King prevail, the estate and lands would be safe from seizure. Should Prince Charles be victorious Rufus could claim the vagaries of old age got the better of him. A bit of playing both sides against the middle, but Rufus hadn’t counted on loosing all of his sons and their sons… everything he held dear.

Those who had minor wounds recovered sufficiently to travel. Two of the three remaining badly wounded men had died and were buried just before MacTavish’s return, leaving the count of eight remaining men, plus William. After dividing the rations, they all agreed it was time to leave the shelter and proceed on their separate journeys. At the first light of dawn they began leaving by groups of twos and threes.