THAT DAMNED PARROT

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

Karl Reinert was a crusty old fart who kept to himself for the most part. I later learned that the crew thought it was because of his heavy Danish accent and his slow responses (probably because he was taking time to mull over what was said, then translating between his native tongue back to English and by that time the thought or topic was out of sync with the rest of the conversation). He couldn’t understand why we didn’t burst out laughing at a punch line of his joke until we had taken the time ourselves to translate what he had said.

He had taught himself English by reading newspapers printed in English and Zane Gray novels he found aboard ship. Because of this, his pronunciation was often wrong or the accent would be on the wrong syllable. For example the word “vegetable” always came out of his mouth as “weG-a-TABLE”, “bottom” was “button”, shrimps were “skrimps” and our Chief Mate, “Hugh Rogers,” was “HuG RoGGers”….all “G’s” coming out hard in his translation. I won’t attempt to write as he talked, but I think you get the picture.

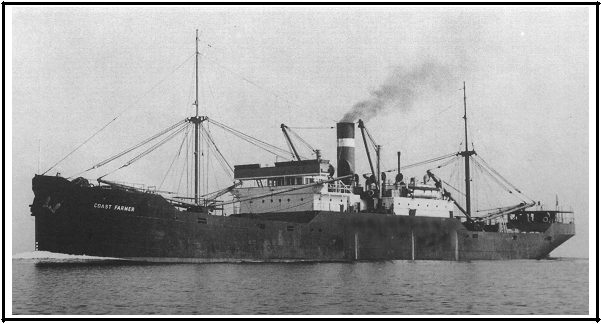

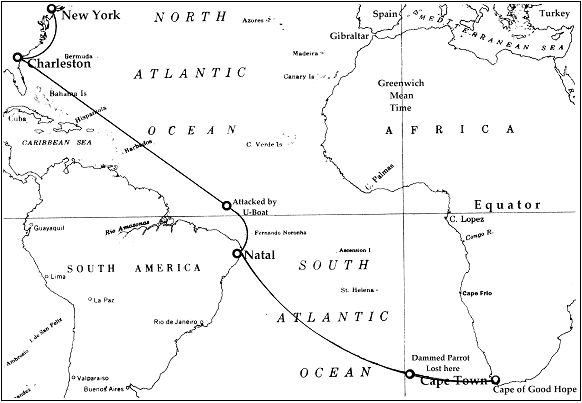

I was a Deck Cadet fresh from several months of classroom studies and on my first off-shore assignment aboard a World War I “Agency” ship. The ship, built at Newark, New Jersey by the “Submarine Boat Corporation” had a profile of the well known “Hog Islander” but was somewhat smaller at 5,500 tons and we were bound for who knows where during the summer of 1942.

So, I was assigned to share a cabin with one of the ship’s two Third Assistant Engineers, Mr.Reinert, now acting as a Deck Engineer, and his parrot….Mr. Reinert wasn’t a bit happy with this arrangement nor was his “damned parrot”.

A Deck Engineer on most merchant ships is considered a senior deck rate much like a Bosun. The position is seldom if ever held by an Officer but on this old ship I could see the need for all the help we could get. I found out later that a South American Shipping Company had been losing money operating the ship and the US Government stepped in and repossessed her, then turned her over to the Army Transportation Service.

There had been no time to lay the ship up for extensive repairs. A World War I, 4 inch cannon was quickly mounted on the stern and a couple of .50 caliber machine guns mounted on the housetop. Every hull that could float and make headway was being pressed into service.

Being somewhat naive and remembering the lessons on protocol at the Academy, I showed up in full uniform (including tie) at my first evening meal in the officers’ mess. I was quickly introduced by the Chief Mate as “The Commodore”, a tag that followed me for many years. Seeing my embarrassment at my new title as the ships officers guffawed, Mr. Reinert motioned for me to take a seat on a green leather bench next to him. His act of compassion created a bond, at least on my part.

After the meal I went to my cabin planning to remove my high-pressure uniform and change into working clothes. As I opened the cabin door I was attacked by a maniacal creature with flapping wings and feathers flying everywhere. The screeching and inhuman sounds coming from the bird forced me to back out into the passageway, slamming the door behind me. I set off immediately looking for Mr. Reinert.

As I charged down the passageway, I was told to report to Mister Hugh Rogers, the Chief Mate, at his cabin. He ordered me to assist and make sure that the forward cargo booms, winches and hatches were secure and ready for sea. And, since I was bunking with the Deck Engineer, I would be his assistant. (I was in training as a Deck Officer and Navigator and fully expected to be assigned to bridge watches….what a disappointment!)

It was chilly for May in New York, with a brisk wind making it seem even colder. And there I was in the light uniform I wore to dinner, which didn’t afford the warmth to go out on deck inspecting and securing for sea. Lucky for me I ran into my new boss as he was entering the passageway leading from the forward deckhouse.

“Mr. Reinert, your bird won’t let me in the cabin. I need to change into some work clothes and get a jacket so I can help make ready up forward for sea.” I really wanted to say more but remembering the instructions on diplomacy, I bit my lip.

“Follow me son and I’ll introduce you to Molly. Once you’ve been properly introduced she’ll tolerate you. Then it’s between you two to make friends or not.”

I followed him to our cabin….as he slowly opened the door he started talking very softly in what sounded like baby talk, “It’s only me Molly… Back away and let me in… That’s a sweet baby.”

“Do I have to go through that every time I want in?” I asked.

“Only until she gets to know you.” He turned and smiled, exposing a mouth full of gold filled teeth clenching on an unlit cigar stub. “Get out of those fancy duds grab your jacket and I’ll show you the ropes.”

I was introduced to Andy, the Bosun, as he was directing a group of men securing the cargo booms. Other deck hands were driving wedges as they battened the hatches. Every valve and pipe fitting was leaking steam and when a winch was started it became engulfed with so much escaping steam I could hardly see the winch driver.

“That’s the first job we have to do tomorrow while were underway. The Chief Mate wants both winches on No. 3 in good repair. You re-pack the valves and flanges and I’ll take care of the winches,” Mr. Reinert said, pointing the flashlight beam toward several areas. Darkness was taking over and the steam billowing everywhere left only indistinguishable silhouettes in its fog.

The Chief Mate appeared in the well deck and began talking with Andy. During a pause in their conversation I gave my report on the progress for getting under way and the deplorable condition of the deck machinery. I received not a glance or response from the Mate. Abruptly he began conversing with Mr. Reinert as if I wasn’t even around. “You and ‘The Commodore’ will standby at the anchor windlass when we begin undocking. Until then start tagging all the leaks while we still have steam on deck.” Having tagged the more noticeable leaks we broke for coffee and I ventured to the cabin to stow my gear and check out my bunk. I opened the door nice and easy and began talking in a soft low tone…” Hello Molly….back away from the door like a nice girl.” I slipped into the cabin; all was quiet, no disturbance. That was, until I turned the light switch knob on the bulkhead just inside door…the instant the light came on all hell broke loose! It was just like before only this time I was trapped on the inside. That damned bird was between me and the door and there I was, a grown man, defending myself and yelling at a bird weighing less than five pounds.

The commotion woke an off-watch Engineer in the next cabin who came charging in wearing only his skivvies. By that time the passageway was crowded and Mr. Reinert was trying to elbow his way through the crowd. He finally pushed the last man out of the way and burst into the cabin.

“I told’ja to try and make friends with Molly, Gutt Dammit! She’s never had to share with anybody!” He then put out his arm and the damned bird hopped aboard, its eyes never leaving my face and muttering, I swear, something under its breath.

“That’s it!….I’m going to the Chief Mate and get my berth changed.” I grabbed my jacket and started to leave.

Mr. Reinert grabbed my arm and pulled me right up into his face, almost sticking his still unlit cigar stub in my mouth and snarled …”He’ll eat you alive son….why do you think he enjoys putting a shame on you? He can’t stand you privileged school boys. He thinks the only real seamen come up through the hawse pipes and if he thinks you can’t take it he’ll put even more pressure on you.”

I began to see the old Dane’s logic….I wondered why the mate seemed to talk through me to someone else, acting as if I weren’t around….” The Commodore” tag, plus the Mate assigning me as a helper to an Engineer, was without a doubt to keep me away from the bridge and out of his sight. “It’s sure going to be a long trip,” I thought to myself. Mr. Reinert relaxed his hold on my arm and I stomped out on deck to contemplate my situation.

An Army jeep and a couple of 6X6 trucks drove up on the dock. Three army officers and about a dozen GI’s offloaded with a huge pile of gear and began hauling the bags and cases up the steep gangway. The Chief Mate noticed a bunch of deck-hands gawking at the army group and bellowed out. ”Don’t just stand there like a bunch of rail- birds. Lend a hand….get that gear aboard and be quick about it.”

The pilot was already aboard and the tugs had been standing by for at least an hour. Many of us had been wondering what the hold up was and now our question had been answered.

The gangway was lowered to the dock and all lines were singled up. The Chief Mate and his foredeck-crew were busy on the bow winching in the mooring lines as the pilot’s whistle “tweeted” and the tug’s crisp “toots” responded to the pilot’s commands. We were soon out in mid-channel under our own power.

On leaving the Narrows the crew was betting we would head east then maybe on to Boston to complete loading, instead we headed due south. As I didn’t have to stand a sea watch I went to the cabin to turn in, I certainly wasn’t looking forward to another encounter with Molly so I slowly opened the door and started to ease my way in. I noticed the flicker of flame from a candle in an odd shaped lamp on a gimbal-like contraption attached to the bulkhead over the small desk. The cabin reeked with a sweet odor from the fumes of the candle. In the corner was a large dome hanging from the overhead with a black shroud wrapped about it.

“Come on in lad, Molly’s been put to bed. She’ll not bother you any more tonight,” the old Dane said, climbing out of his bunk, “I’ve cleaned up the place. You can stow your gear in that far locker and the two lower drawers are yours as well.”

He took a bottle from the head of his bunk and poured a thimble-full of clear liquid into a shot glass and handed it to me. I sniffed the glass but couldn’t recognize the odor, I put the glass to my lips for just the tiniest sip. It was the most God-awful tasting stuff I’d ever put my tongue to. But, I wasn’t about to offend the only friendly person I’d met on this ship so I took a healthy swig. It burned all the way down and almost took my breath away. I shuddered, coughed and when I was finally able to catch my breath, caught a faint licorice-like flavor that seemed to wrap around my tonsils and head straight for my toes like a raging fire. As I pushed the glass back towards him he asked, “You want more?”

“No thank you Mister Reinert. What kind of booze is that?” I gasped, “I’ve never tasted anything like it before.” I could tell he already had a few shots before my arrival.

“Akvavit….A Scandinavian liquor, very popular in my country. Molly likes it too. I give her a dram every night before I put her to bed. During the day she’s used to having the run of my cabin and I leave her cage door open so she can come and go as she likes.” Mr. Reinert stopped for a moment to down another swig before putting the bottle under his mattress, “That is, if you don’t mind. I clean and change her cage every day.”

What could I say? I didn’t want to offend the old guy. The nasty stub of a well- chewed cigar was more obnoxious to me than that damned parrot.

While stowing my gear away the old engineer, being in a talkative mood, offered some background on his shipping. He said that he was sailing on a British ship trying to make it back home to Copenhagen when the war broke out in ‘39. Instead he had landed in the US and volunteered to sail on American ships to avoid getting involved in the shooting war. “Now it seems like I’m about to wind up in the middle of it anyhow,” he lamented, then added, “Instead of calling me mister Reinert all the time you can call me Karl like every one else does.”

Karl inquired on my background. I told him that most of the men in my family had gone to sea, either fishing or on coastal shipping. My dad was a skipper on an ocean going tug and that I crewed as a deck-hand with him every chance I could. It was my dad who had suggested that I apply to Maine Maritime Academy for an appointment.

I left the cabin to see what was going on in the officer’s mess. Only a couple of off- watch officers were sitting around playing cribbage so I moseyed up to the bridge deck and out on the starboard wing to gaze at all the lights on shore as we hugged the coast. The Mate recognized me and said “Hi there Commodore, I fully expect you to attend to your class projects even though you’re not assigned to bridge duty. I’ll get with you once we get on a regular routine.” (My class projects were well laid out in my binder. Several hundred questions, covering almost every function aboard ship. Those questions were expected to be answered, reviewed and signed off by the ship’s Second Officer and returned to the Academy for grading.)

“That sounds great. I’d about had given up getting any chance to stand bridge watches after being assigned as a deck engineer/s assistant. You must be Mister Skinner, the Second Officer. I was instructed to introduce myself to you when I came aboard but I got waylaid with other duties until now. My name is Robert Rhode, MMA class of ‘44″ (graduating class two years hence). I offered my hand and we shook.

“Thomas Skinner, Second Mate. Pleased to meet you. I understand and appreciate your situation. Somehow we’ll work around it. He then picked up his glasses and scanned the lights ashore then went to the pilothouse door and ordered the quartermaster to Acome right 15 degrees.”

The helmsman repeated the order and a moment later added, “Steering one eight oh degrees.”

“Hold your heading, course 180 degrees,” responded the Mate. Again the helmsman repeated the Mate’s command.

Seeing that the mate was concentrating on maneuvering and not wanting to interfere, I bid goodnight and left the bridge to go below and turn in.

Early the next morning Karl and I began replacing packing in almost all the flanges and steam joints and we even had to replace several valves. It never fails; when trying to do a quick fix on a valve the stem breaks or the wedge or plug won’t budge. We found the piston rods in the winches were badly scored, it’s a wonder they held any packing at all.

The project turned out to be more involved than we first thought. The Chief Mate was keeping a close eye on our progress and had the Bosun assign several day-watch seamen to assist us.

A few days later we entered Charleston, South Carolina and headed up the Cooper River for several miles. Steam pressure was brought up to the deck and, to our relief, only a few leaks were found and tagged. We hadn’t been tied up to the docks a half hour when a gang of Army longshoremen clambered aboard opening every hatch. A large Army contingent of soldiers, lugging what looked like everything they owned, filed aboard and disappeared down the small mid-ship No.3 hatch between the bridge deck house and engineering quarters.

Large bundles of lumber were hauled aboard and taken down No.2 hatch as well as the No.3 hatch between the houses. Everywhere saws were singing and nails were being driven. Thousands of bales of hay were taken down into No.2 hold and nobody had the slightest notion of what the strange cargo represented.

Mister Rienert and I were instructed to assist the shore-side pipe fitters in piping the No.2 hold for additional fire mains. Like a bolt of lightening it must have come clear to the old Dane. “Animals.” ….that’s all he said for the longest time, “Animals,” he repeated, “we’re going to transport animals.”

Cargo was shifted from hatch to hatch to trim the ship and finally all was closed up and we were under way. The G.I.’s in No.3 were still working and only came up for chow and an occasional breath of fresh air.

We had been underway five days and were still heading southeast. All were well aware of the U-Boat activities in the area and we had what we thought were several sightings of subs and/or their periscopes.

When I went to the bridge for my Cadet course review with the 2nd Mate I’d hear just enough gossip to spook the hell out of me. There was mention of a ship sinking nearby. We began zigzagging at irregular intervals.

On one of my bridge visits the Chief Mate called me aside, inquiring of my duties. He seemed very congenial and took interest in my replies. He indicated that he was satisfied with our deck engineering progress and pointed out that those duties fell under the Deck Mate’s jurisdiction and since I was in training it was considered part of my cadet course. He also commented that he heard that I came from good sea-farin’ stock.

As I left the bridge I pondered the Chief Mate’s response and considered myself lucky to have as good a friend and instructor as Karl Reinert.

By this time I was able to come and go from the cabin without a big scene with Molly. We weren’t the best of friends as yet; in fact we just seemed to tolerate each other.

One day after lunch I climbed up into my bunk to relax and dozed off to sleep. Something woke me. I opened my eyes and found myself looking straight into Molly’s beady little black eyes. She was just sitting there like a statue on the wooden side-board of my bunk, only four inches away and staring directly at my face. I didn’t move for a full minute, I was afraid if I startled her that her sharp beak would tear off my nose or gouge out my eyes. She tilted her head, first to one side then another as I eased up and back against the bulkhead of my bunk. I finally realized she meant no harm and let out a sigh of relief so big that my breath ruffled her feathers. My sigh evidently broke the spell and she turned and deposited a sizeable plop of parrot poop on my mattress before she fluttered down to Karl’s bunk. That Damned Parrot!

We had been plowing head-on into a fairly heavy sea for two days and most of the Army men were taking it pretty hard. The thought of any merriment soon to take place was farthest from their minds.

The next evening just before six, I had just sat down for dinner when the general alarm bell started clanging. The look-outs had spotted an object a few miles off the port quarter. The Armed Guard immediately manned their guns and the rest of the crew took to their stations. I was in charge of a fire station at the No. 5 hatch. We laid out the hose, opened the nozzle and turned on the fire main and let the water shoot over the side.

I saw a column of water erupt several hundred feet abeam of us, as did everyone else in my gang. Immediately we all ducked for cover. It seemed like forever before we heard the U-Boat’s cannon report.

On occasion when I think back of this incident, I wonder why I was so stupid that I risked coming out from my shelter just to look at the vessel shooting at us. She had gained on us some since first sighted but was diving into each swell and kicking up so much spray that I don’t know how the men firing the sub’s gun could keep from being washed overboard.

Because of our more stable platform our 4″ was firing three and four shots to their one. The .50’s opened up, but with little effect other than kicking up a lot of spray, and they seemed to constantly jam and time had to be taken to clear their mechanisms.

For some unknown reason the sub broke off her attack, either because of the coming darkness, or maybe we scored a hit that damaged her, or she feared possible interception knowing that we transmitted a SSS message, or maybe she had a mechanical breakdown, or….so much speculation as to “why”, but no sure answer.

For the next two days until we arrived into the safety of the harbor of Natal, located at the north eastern bulge of Brazil, all we could talk about was how lucky we were to be alive because there was no way we could have out-run that sub. But the mystery of why she quit still puzzled us. We didn’t hold our shellback ceremony but we were assured we would get our certificates.

On arriving inside the small harbor of Natal two ancient steam tugs with tall stacks belching black smoke that smelled like coal burners nuzzled us along-side a Liberty ship that was lying at anchor. Two camels, made up from large logs tied together, kept the two ships from rubbing their hulls together. The Liberty ship’s bow was down and her stern was high enough to expose her rudder and skeg but there was no sign of a prop or shaft. We found out that she was a dead ship. Repairs had been attempted but it was determined that there had been so much damage to her stern tube when the propeller shaft broke that it would require her to be put in dry-dock for repairs as soon as the government could locate one within a reasonable and safe towing distance.

Most of her crew was sent ashore or home until a replacement ship could arrive, transfer her cargo and continue on and deliver it to the Liberty’s original destination. We found out we were that replacement ship.

It took nearly two weeks to load cargo from the Liberty’s hatches and a whole lot of creative rigging to whip from our winches through her booms, to our deck then down into our holds. The more we loaded the deeper we settled in the water and the higher the Liberty went, until our booms barely reached the Liberty’s weather deck.

For two weeks there was no opportunity for the ship’s crew to have liberty ashore. When we weren’t loading we stayed busy splashing grey paint all over the ship to cover up a hull that had more rust showing than any original paint.

One day the Army’s contingent was herded onto a small ferry to go ashore on liberty….or so we thought. We razzed them as they left the ship, yelling for them to save a few virgins for us.

A day later the Army troops returned aboard two wooden barges with fences built all around the sides and a herd of mules packed in solid. The old Dane had been right….”Animals”. The loading of our four-legged passengers began. We first started with bringing aboard only one mule at a time, then two, three and finally four. It took two full days to get them all on board and into their make-shift stalls. You’ve never seen so much pootin’ and pissin’ or heard such squallin’ in your life; and the Army wranglers were cussin’ and yellin’ just as loud.

It didn’t take long for everyone to know just what our cargo was. You could smell us down-wind for a mile and aboard ship the stink permeated every cubic inch of air. We rigged up wind sails, canvas air scoops to try and circulate the air in the No. 2 and No. 3 holds.

During our stay the Armed Guard was able to requisition or steal two 20 millimeter cannons, mounts and ready-boxes from ashore. The skeleton Armed Guard crew from the liberty pitched in to help set up the new cannons.

We finally completed the cargo transfer, battened down the hatches and put out to sea. Our worry over the threat of subs again filled our thoughts and kept the crew edgy.

Noontime, three days out and on a heading of South by East at 10 knots. The weather was hot, humid and no breeze other than what the ship made. The sea was as smooth as glass. Everyone was hunting for shade, anywhere they could find it. The decks became so hot you didn’t dare touch it with your bare skin.

Karl brought his parrot and cage topside to give poor Molly a little relief. Several crew-members were sitting around in the shade of the engine-room skylight house on the boat deck dozing. The old Dane let Molly out of her cage and she perched on his shoulder, nuzzling his cheek and “talking” to him in low clucks and squawks. Everyone was silent and just staring out to sea, searching the horizon or just daydreaming. All of a sudden horns and bells sounded….safety valves popped….steam screamed as it escaped up the stack from the boilers….Everyone came to life, and Molly took flight. I saw her flapping her wings like an overfed duck trying to take off from a pond. I lost her as she circled the ship. Poor Karl was going out of his mind calling for her to come back….but to no avail.

The ship lost headway. No more sound of the turbine whining and soon everything went quiet….dead quiet….We just sat there gently rolling about in the calm sea. Any breeze we had before was now gone.

Karl knew exactly what had happened and started for the engine-room, begging me to see after Molly but the general alarm bell and the whistle interrupted our conversation.

I thought I saw a flash of Molly flapping her wings out of the side of my eye when the ship’s whistle blasted. But I had no time to confirm what I thought I had seen as I took off for my fire station.

Word passed around the ship that the lube oil system had automatically shut down the main engine when it had gone above a certain temperature. The fireman didn’t have time to bank his fires before the boiler steam pressure lifted the safety valves. That’s what caused all the racket.

The black gang was working feverishly, going through every point of the lube oil cycle trying to figure out what caused the failure. They certainly didn’t want to be caught down below in the engine room, dead in the water, with U-Boats roaming around looking for a fat cargo ship to put a fish into.

All afternoon and into the night we sat there. The heat was unbearable. Most of the GI’s brought their cots on deck as did I and many of the ship’s crew. I don’t know if we did this because we were really scared of being caught below if a torpedo should hit or if it was the heat. The stink from the mules was almost as bad as the heat. Then the flies found us and what we thought couldn’t get any more miserable suddenly did.

The mystery of the lube oil problem was solved. While we were lying in the warm waters of Natal, sea life (including shrimp, kelp, clams and assorted small fish) were sucked up with the cooling sea-water into the lube oil heat-exchangers and completely clogged the system causing them to over-heat. Both ends of the heat-exchangers had to be removed and near a hundred of the 12 foot long tubes had to be ram-rodded to clear the obstructions.

By dawn of the next day we were under way again to the relief of everyone aboard….and still no sign of Molly.

That morning one of the mules was found dead in its stall without any obvious signs. Of course the Army Animal Doctor was afraid it might be a disease that could infect the herd and requested of the Captain that the animal be brought topside and tossed overboard, along with all the manure that had been accumulated. He also suggested that all the stalls be hosed down with high pressure hoses.

The Captain wanted to hold off discharging anything until after nightfall so as not to leave a telltale sign of our presence for any lurking U-Boats. However, the Animal Doctor was very convincing about the contamination now that we were so badly infested with flies. With the threat “that it could even get worse,” the Captain reluctantly agreed.

The cargo booms were rigged and a portion of the hatch was opened. Large hod carrier-type wheelbarrows were filled with manure, hoisted and emptied over the side along with the one carcass.

I could tell that Mr. Reinert was taking the loss of his parrot very hard. All of his off work hours were used in searching the ship for Molly in the off-chance she was still aboard somewhere. At night he would sit topside and call out for her in baby talk much like he did when we first went into the cabin together, as tears rolled down his weathered cheeks.

In the beginning the crew was sympathetic and truly understood the old Dane’s misery. But after a couple of days watching a grown man wander about the ship, always looking aloft, and calling out soft and sweet comments they began to wonder….

As we worked our way down to the southern tip of Africa the weather turned cold and blustery. July in the northern climes was in the middle of its summer but in this Hemisphere they were in the middle of their winter and this far south, a freeze was not uncommon.

Karl took to the Akvavit bottle and began brooding openly. I covered for him where I could until I finally ran out of excuses for his absences at meal times. Almost everyone thought they had seen Molly. Some thought they had seen her at the cross-trees, others saw her flying around the stack but they hadn’t seen her land. It had been eight days since she bolted and everyone was wondering where she could get food or water.

Two days before entering Cape Town, South Africa, we had to dispose of two more mule carcasses. It was unknown what the cause of death was, as no open sores or bruises could be found anywhere on them. The Army Medic did an elementary autopsy but nothing conclusive was revealed and he saved some parts of the dead animals’ organs to send to a laboratory ashore when we reached port.

With the yellow pratique flag flying as we entered port, the pilot boat escorted us far away from any other ships or harbor facilities. We anchored and were told to wait for the Port Medical and Immigration officials to clear us.

I met the Chief Engineer for the first time when he come calling on Karl. I had brought some dinner to the cabin but Karl wouldn’t even look at it. He was, I thought, so shnockered he couldn’t even get out of his bunk.

Karl often spoke of his boss as being the best Chief Engineer he ever sailed with. I had asked Karl why that was and he answered that it was because he never once came down into an engine room.

The boss Engineer was portly and wheezed with every breath he took. When he came into the cabin he reached under the mattress at the head of Karl’s bunk and brought out an empty Akvavit bottle. Handing the bottle to me he told me to open the old Dane’s locker and bring out another bottle.

I opened the locker, reached in and fumbled through a case that was stacked on top of what appeared to be another unopened case and brought out a full bottle of the liquor.

“See that he gets a shot every hour and make sure he drinks a glass of water with it. He’ll eat when he wants to. I’ve been through this with him several times before, but, it looks like I may have to put him ashore this time.” The old Chief Engineer had difficulty getting up from the chair. Either it was from his age (he appeared to be 70 or better) or from his excess weight. As I watched him I thought he wasn’t long for this world. Here was a case of the war creating a need to crew ships with anybody holding a License. As he left he said he would ask the skipper to send the Army Doctor to look in on Karl.

I decided I couldn’t stay in the cabin that night and went to the sick bay to see if I could flop on an empty berth for awhile. Instead I ran into the Army Doctor and explained Karl’s condition. He said that the skipper asked him to look in on Mister Reinert and was just getting his bag and a few medical supplies together to examine him. He followed me to my cabin and bent down to examine the old gent. He suddenly stood up straight and announced that Mister Reinert was dead.

I couldn’t believe it. A man doesn’t just drop dead because he drank a little too much….and it surly couldn’t be from a broken heart over the loss of his parrot, could it? This was unreal.

The doctor had two men come and take Karl’s body out on deck and wrap him with sheets and a blanket. It was almost freezing on deck so it was decided to stow him outside on a cot until morning.

The next morning the port’s medical inspector and his crew boarded and asked everyone aboard ship to present themselves for a routine medical examination. When they were told of the dead body they didn’t want anybody coming close to them and hastily started backing away towards the boarding ladder.

Our Army Doctor convinced them that we had no contagious diseases aboard and requested, since the ship was going to be held in quarantine, if they would please take Mister Reinert’s body ashore and do an autopsy. He also requested that they examine the gland samples of the dead mules.

Any shore leave was out of the question. We were denied any contact with chandlers, agents or bumboats until we could pass a clean bill of health.

Three days had gone by and no word from the port officials and, again, no sightings of Molly.

As if we didn’t already have enough problems the Chief Engineer had a stroke or some kind of seizure and we had to blinker-light ashore for help. The medical people came out and took him to the hospital.

I took everything belonging to Karl, bagged it and boxed it and stowed his gear in the gyro-compass locker. His bedding was taken to the trash pile that was getting bigger by the hour. I soogied the cabin with the help of a messman and passed along a few bottles of Akvavit. No use letting it go to waste (besides most of the rotgut you’d buy ashore could poison you).

Early the fourth morning the port official’s launch headed our way with departmental flags of every nature flying from its yards. A large retinue of officials came aboard asking to be directed to the ship’s master and were directed to the officer’s mess. Sometime later word was passed for all officers to queue up for a health examination in the officer’s mess.

It was a simple check-over for everyone until they got to me. I was put through the wringer, every part of my body was poked and prodded, blood was taken, I had to piss in a bottle and spit in a little tub. The medical examiner asked questions for nearly a half hour and many of the questions centered on Mister Reinert and his parrot.

I found out that Karl had died from some exotic disease called Psittacosis (Ornithosis) or more commonly known as “Parrot Fever”. The doctor said that Karl’s liver was in very bad condition, due to drinking no doubt, and was unable to ward off the parrot disease.

“You are going to be placed ashore and held under observation for two weeks or until we feel incubation of the disease has passed,” announced the Port Cape Town’s Medical Examiner.

I turned to the Chief Mate and asked if I was going to be left behind. “I’m afraid so, son. I sure hate to lose you Commodore. I’ll write a letter of recommendation. You earned it.” This coming from a man who couldn’t stand young whipper-snappers of my ilk two months ago. All I could think of at that moment was to ask for my shellback card.

I saw the animal doctor and asked if he found out why the mules were dying. “They found a poison in their glands from eating some kind of foliage found in the back woods of Brazil. We can only hope that was the end of it.”

I spent two weeks at the infirmary in Cape Town and I was declared free of any disease. I stopped in to visit with the Chief Engineer who, by this time, was looking good; it seems that along with proper medication they had put him on a diet. I told him what Karl said about him being the best Chief Engineer he ever sailed with and he busted out laughing.

I also mentioned that I was disappointed that I had to leave the ship and he said that I wouldn’t have liked India or Burma during the monsoon season.

So that was our destination, I thought to myself, wondering what the hell they were going to do there with a bunch of mules.

An American flagged liberty was heading home and was short a mate. I was offered the position and jumped at the chance. As I climbed the boarding ladder I was greeted with, “Welcome aboard Commodore.”

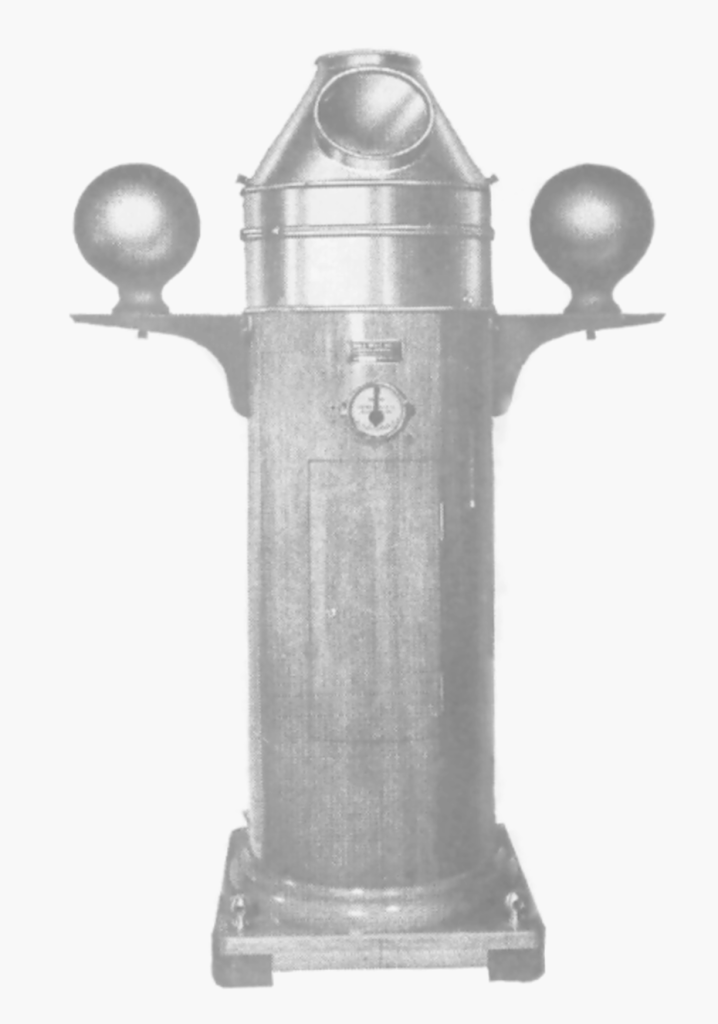

BINNACLE

COMPASS HOOD QUADRANTAL SPHERES

And MAGNET CHAMBER BELOW