JONAH & THE MARK OF CAIN

Ron Stahl

CLICK HERE TO VIEW IN ORIGINAL PDF FORMAT

Men of the sea have long been accused as being a superstitious lot. That especially applies to fishermen as they think that when paying their debts at the full moon good luck will fill their nets in the coming month. A few will filch something off a successful competitor’s vessel in hopes of bringing a bit of good Karma along with it, and a true mariner won’t whistle while at sea for fear that the devil will unleash his one mighty power (the winds). Nor will a seaman kill a seabird for fear of destroying the soul of a departed seaman, or will he lay a line or hose counter-clockwise for fear of invoking the wrath of God or that of his skipper. But…. none of this really means that seamen are superstitious…they say, of course, that they are only following “wise sea traditions”.

Long before the 1900’s, Priests or Ministers were often employed to christen a new ship at her launching by breaking a bottle of wine spirits on the ship’s prow, a custom reverting back to the dark ages when sacrifices of blood were used beseeching God’s mercy and good fortune for the vessel and her crew. Seamen continue to follow proud traditions that have been handed down through generations. Many seamen, including fishermen, hesitate to sail on a Friday, the day of Christ’s crucifixion, for fear of that old prognostication of trouble, that a voyage begun on a Friday is sure to be an unfortunate one or, as the fishermen say, “A Friday’s sail, Always fail”.

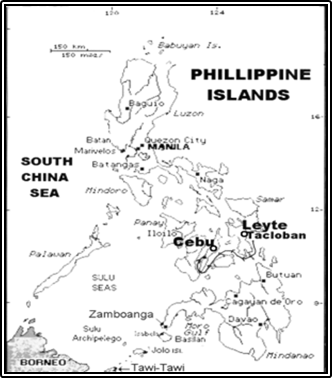

I never considered myself a religious person. I do believe in a greater being and have done a fair amount praying in my life…. and that is about the extent of it. On a Friday in mid February 1945, while anchored off the beach at Tacloban on Leyte Island, Philippines, we awaited my vessels turn to tie up at the makeshift floating docks to off-load cargo that had been taken aboard two weeks before at the island of Biak off the north-west coast of Dutch New Guinea.

A launch tied up along side bringing the replacement for our 1st Officer, who had just completed his contracted tour of duty with the US Army Transport Service. The launch was standing-by to take a mess-man ashore who had come down with bouts of high fevers and chills for most of the trip up from New Guinea. Because the Captain still had occurrences of the disease himself, he had diagnosed the ailment as a bad case of malaria.

I boarded at Hollandia about a month before, just prior to the ship”s passage to Finschhafen, Biak and Moritai and was on my first assignment as a Mate. I had served as a temporary Mate before on other boats (mostly small coastal supply vessels) until a licensed or classified Mate was available to replace me.

As a little background as to why I was recommended as Mate when I boarded this ship in Hollandia, I had been temporarily assigned for limited shore duty (because I had to go to the hospital for treatment every other day for a bad case of jungle rot) as an operator on the Harbor Master’s MTL Pilot Launch to ferry the harbor pilot to his assignments and then to pick him up at the sea buoy to return back into the harbor.

About 0400 one morning the pilot rousted me out of my bunk and waited for me to dress, explaining that we had a special assignment to help a troopship get underway while she could take the advantage of the tide.

During the night an Aussie Corvette had run aground in the harbor and the three largest tugs in the harbor were getting ready to tow her off the bar at the tide change. One tug caught a wire in one of her props, so they used her on one side to try and break the suction. The other two had been working all night without any success. Whoever was in charge wouldn’t release any of the tugs to help the troopship get underway from the dock.

Dawn was approaching as we arrived at our destination up harbor, and coming into view through the morning haze was a huge ship with many people manning the rails. I guess they were watching the exciting events across the bay at the Corvette.

On our way over the pilot had filled me in on the procedure he wanted me to take in helping him turn the ship around to head towards the entrance of the harbor. “When I’m ready I’ll give three short blasts on the whistle and the ship will start easing astern while we take a strain on our spring lines. When you see the bow start to inch out from the dock, put and keep your bow 90 degrees to the bow of the ship at all times and start pushing with a full throttle until I give a single long blast… then back off.”

The deckhands high up on the bow asked what I was going to do and I replied I was going to turn their ship around. They started laughing and making jokes and the people who were watching the main event must have tired and came over to our side of the ship when they heard all the joking and kidding around; they even contributed with their ridiculing remarks.

I told the crew I hadn’t had breakfast or coffee yet and several minutes later they called down and a package was tied to the end of a heaving line with a scrambled egg sandwich and a pitcher of coffee.

My little 45-foot tug had a 120 hp. Buda Diesel very similar to the one I operated up at Biak, and was a very easy vessel to operate.

I heard the winches start working as the crew began taking in the mooring lines so I nudged my bow against the hull.

Three blasts on the whistle. I revved up the engine and started pushing; it seemed to take a long time to see any movement. Then ever so slowly the big ship’s bow inched away from the dock as her engine was barely going astern, pulling a hefty strain on the doubled up spring lines. I had no problem keeping my tug 90 degrees to the ships hull. The ship’s engine stopped but we continued to swing out into the channel. Finally, the long blast on the ship’s whistle told me that we had done it! But what was really the icing on the cake was the spontaneous cheering from the on-looking passengers at the rails.

I followed the ship out to the sea buoy and then went alongside to take on my pilot, he met me with a broad grin and handed me a steak sandwich.

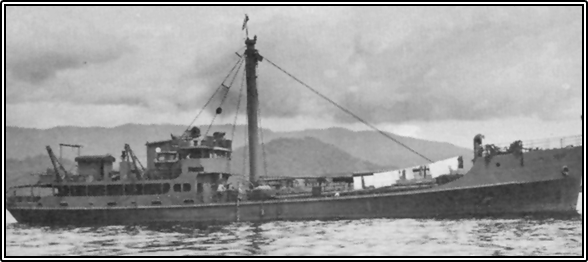

Not long after that incident I got a sheaf of documents with a notice to go to the back harbor and go aboard an FS boat and hand them to the Captain.

Now, a month later, the departing 1st Mate of our FS Boat learned for certain at Hollandia that he was scheduled to go home upon reaching the Philippines. He had told me only that morning that he was so eager to get off the ship and go home that he pushed for me to fill the Mate’s berth over the Captain’s reluctance. But, because the ship would have had to wait a few extra days for another replacement to arrive, and then sail on a Friday, it didn’t take much urging for the Captain to accept me. “So, that was the reason,” I thought to myself, “that the Mate took me under his wing and crammed all the information he could into me… just to prove to the Captain that he had made a good choice. But, until today, he failed to mention anything about the Captain’s reluctance to leave port on a Friday, and with a new untried Mate.”

I was saying my goodbyes to the departing 1st Mate at the boarding ladder when a deck hand informed me that the Captain wanted to see me up in the chartroom located on the bridge deck.

Oh oh, here it comes,” I muttered aloud to myself.

Don’t worry, you’ll do OK,” said the departing Mate as he climbed down the ladder into the launch, waving goodbye, “Just remember what I said about his superstitions.”

I made my way up to the wheelhouse and entered a compartment where all the charts, books and navigational instruments were kept. Two men were huddled over a sheaf of charts. The Captain walked the dividers up lines of one chart while the other man was sliding the parallels back and forth between the chart’s “compass rose” and then penciling zigzag lines on another chart. I cleared my throat to make my presence known.

Come on in. I want you to meet our new Chief Mate, Mister Jones. He just came over from the States. Mister Stahl meet Sam Jones”. The Captain added, “Mr. Stahl’s our other Mate.”

We shook hands as I offered, “welcome aboard Mister Jones.”

As on other small Army Transport vessels with only three officers on deck, they identified those positions as Captain, 1st and 2nd Officers or Mates. On larger ships with four officers I would only have been a 3rd Mate. On yet smaller vessels there would be just a Skipper and single Mate.

Come…. take a look”, motioned the Captain. “Our orders have been changed. We’ve been rerouted to deliver some of our cargo to another area. Mr. Jones came directly from the Harbor Master’s office with our new orders.”

I studied the new Mate as he and the Captain poured over the instructions and charts; his head would turn from the typed page to the chart, back and forth. I caught a glimpse of it again, a red triangular patch that looked like a tattoo above his left eyebrow, not much larger than a quarter. No, it wasn’t a tattoo it was more like a birthmark or a scar of some sort. I became fixated on that scar.

Without looking up, Mr. Jones cautioned me, “Pay particular attention to the depths in this area, there are only a few fathoms at mean low tide.” He glanced up at me and caught me staring. It embarrassed me and I apologized saying, “I’m sorry,” and hoped that would be the end of it.

Our trip from Tacloban on Leyte

to the Western shore of Cebu Isl.

Sea watches were set and the ship weighed anchor before lunch. I had the 4-8 watch and decided to go to my cabin and look over the books and manuals the departed Mate had left behind.

Amongst the books, I came across a Gideon’s Bible that had a tasseled page- marker resting in the first chapter of Genesis. I hadn’t read very far when I came across an underlined passage where Cain slew his brother Able for showing him up before God, with his grand offerings. Instead of punishing Cain for murder, God put a mark on his face for all to see and decreed that, “No one should ever harm him.”

That mark above Mr. Jones’ eye intrigued me and conjured up visions of when I was a young lad. I could still remember the Bible-thumping preachers at Aimee’s Temple loudly shouting the ravages of sin and the mark of Cain…. and right now I couldn’t fathom what the one passage had to do with the other or why Mr. Jones and his mysterious mark brought back those memories.

At 1800 hours, with dusk fast approaching and two hours into my watch, we were about to make a crucial course change. The Captain and the new 1st Mate, Mr. Jones, were taking bearings with the pelorus (dummy compass) on opposite sides of the bridge wings. They were taking running fixes off the headlands and peaks of several islands. I was with Mr. Jones jotting down the different degrees as he was calling them out. He would take his notes and go to the charts to add or correct the running fixes on the rhumb line from the last dead reckoning position. I was most impressed with his apparent navigational expertise.

Mr. Jones ordered a change of course and waited with the Captain until everything seemed to be going smooth, and then together they left the bridge and went below to dinner.

I took up my position on the starboard wing feeling very confident that all was going nicely. The warm breeze, starry night and the moon casting its light on the sea and small islands seemed so pleasant…. until a big shadow appeared directly ahead on our course. I rushed into the wheelhouse and asked the man at the wheel what course he was steering. The helmsman called out his gyro heading, which was the course marked on the chalkboard. I ordered the helm hard over to port and rang down to the engine room for stop engines…. and got no response.

It came out later that two of the Engineers were eating dinner, as were the Captain and Mate. The 3rd Engineer had stopped by the officer’s mess to grab a cup of coffee. The one Oiler on watch could only handle one set of engines at a time and, of course, unknowingly chose the wrong set of engines to start with. Imagine this; the starboard prop came to a halt. Rudder was hard to port (to turn to the left) but the port engines were still running full ahead…. they were heading right for the mass ahead when I rang down for both engines “full astern”. This new order only compounded the confusion already existing in the engine room.

In no time at all I had plenty of company on the bridge, but still no response from the engine room. Later, which seemed like forever, we could feel the vibrations of the engines being put astern. The Captain was on the phone to the engine room demanding an explanation. For a moment no one honestly knew what to do. I remembered just standing there looking at that huge dark mass getting ever larger…and then we hit it. Not a hard crash, more like a slow ploughing sensation until the ship surged to a stop.

For what seemed like an eternity everyone just stood there looking at one another. Then the spell broke and the Captain rang down to stop the engines. The bridge telegraphed immediately, acknowledging the order.

OK, what the hell happened?” the Captain uttered through clinched teeth.

I was looking at the gyro-compass and comparing it with the magnetic compass. They were only the usual fifteen or so degrees apart. I spun the helm full left then right, the rudder indicator stayed with the rudder angle changes. I was about to answer the Captain’s question when the ship started swinging around, sliding off the sandy shelf it had wedged itself in, and within a minute or so we were afloat and moving astern towards another large mass a short distance away.

The Captain took over the bridge. He telegraphed the engine room for slow ahead and called out for the helmsman to bring the ship around to a new heading as they worked themselves free from almost another incident.

With the moon-glow shining on the water, the men on the bridge could see swirls being stirred up by a very swift current as it veered off a jut of land; it was so obvious that no one had to say a word. Somehow the main thrust of the current must have grabbed hold of the ship from abeam and even though steering the proper course, drove the ship side-ways onto that sand bar.

There was no apparent damage to the hull and we continued on our way. Captain and Mr. Jones huddled in the chartroom pouring over charts and referring to a large volume of Oceanographic Sailing Instructions.

My watch was over and I had completed entering the incident into the watch-log, including a capitalized FRIDAY above the date and a memo of a rapidly dropping Barometer. I signed the log, but wasn’t about to leave the bridge until I was officially relieved. The Captain and Mate were not saying much but everyone could tell that the Captain was pissed. Unfortunately, I couldn’t tell if it was at me because I had been on watch, or the incident as a whole.

The ship was approaching another major course change to enter a narrow and shallow strait between two islands but first we had to clear several smaller islands. The Captain was heard muttering, “Now, dammit, let=s not make any more stupid mistakes.” I didn’t think the statement was meant for me. Mr. Jones was standing close to the Captain and I was on the other side of the wheelhouse. The man at the wheel looked at me with a sneer on his face and I just glanced up at the overhead in return.

After the maneuvering was completed, I asked the Mate if I was relieved. I was told to go below and get some sleep.

Sometime during the night I thought I heard a change in the rhythm of the engines and the grumble of the anchor chain running out, then silence. I turned over and went back to sleep.

The 12-4 AB knocked on the cabin door, opened it and called out “three-thirty” then waited for me to acknowledge his “wake the watch routine”. I got up, washed my face and on my way up to the bridge swung by the galley and grabbed a cup of coffee. On reaching the bridge I didn’t say anything to Mr. Jones as I was thinking of the Captain=s angry question of less than six hours earlier. I had yet to think of an adequate response and was quite reluctant to open up more questions from Mr. Jones.

Good morning Ron. The Captain left orders for the Army gunners to split up into watches to prevent any boarders. He said he had heard reports of the locals going aboard vessels and creating havoc when he was on his previous trip to this area. The weather is turning bad…have your watch trade off standing lookout on the bow. Don’t hesitate to call me if anything seems amiss…OK? By the way, we read your log entry. The Captain was very upset about something you wrote, so I=m going to have to get with you on the proper language to use when you try to explain certain problems. If anyone were to read your entry they’d think that some mysterious spirit took over the ship and put us hard aground instead of just touching the bottom.” I thought I caught a hint of a smile as the mate was explaining his appraisal of my entry into the watch log.

Wind and rain showers were pelting from every direction and I couldn’t make out any landmarks to take bearings on to insure we had remained securely anchored. I wondered why they had anchored in such an isolated spot, and just took it for granted that maybe they were supposed to arrive at the new destination at a particular time or that Sparks might have received a change in destinations while monitoring his radio.

The blackboard had instructions to call the Captain, Mate and Cook at 0530 to prepare to get underway. The rain-squall had passed and after an early breakfast they started to weigh anchor but everything ground to a halt with less than half the chain retrieved. Each time Mr. Jones threw the controller lever the windlass motor would just hum.

Mr. Jones and his anchor crew went below into the forepeak locker where the controller panel was. They tinkered with the breakers and kept asking the crew topside to push the lever this way and that way but still the motor would only hum.

The Captain had the crew start rigging the cargo booms to haul the anchor chain over the starboard mid-ship gunnel in the well deck. This ship was an earlier version of the many that followed and had no bulwarks in the well deck but instead had stanchions and chain for lifelines, making for a very wet deck at sea. Mr. Jones was still trying to get the windlass motor running when the Captain sarcastically called to him, “Quit tinkering with the damned windlass and get to work on rigging the cargo boom.”

The whaleboat was put over the side. The Captain instructed me on the step-by-step procedures he wanted me to perform while in the boat. I was to take a heavy mooring line and double-hitch it to the anchor chain just below a marlinspike that was jammed into a chain link. The crew at the cargo winch would bring in the line until the men at the gunnels could reach the anchor chain and attach a chain stopper that was secured at the mooring bits; they would then lock the heavy duty chain and grabber that was attached to the cargo hook to the anchor chain.

By hoisting the cargo hook along with the anchor chain about twenty feet above the deck and again securing it with the stopper at the gunnel, they could slowly lower the hook and with considerable effort, the deck crew could fake the chain on the deck in neat orderly rows. This procedure was repeated several times… until disaster struck.

The well deck had about six feet of freeboard because the ship was originally loaded to her so-called plimsoll mark and was now listing to starboard with her boom swung out and the added weight of the anchor chain. After about the sixth time of this slow and drawn out procedure, the chain was lowered to the deck. The stopper was supposedly secured at the gunnel. I was bringing the whaleboat back towards the side of the ship; we always backed off each time the chain was being hoisted just in case something gave way.

For some unknown reason the anchor chain started running over the side and back to the bottom of the bay. The chain snaked its way fore and aft almost as if it were in slow motion. Everyone started scrambling in all directions. Several hours of hard work in the extreme heat and humidity was lost in just a matter of a few seconds.

The Captain had gone aft earlier leaving Mr. Jones in charge of the operation. I was a few yards away from the ship in the whaleboat when the Captain came charging onto the well deck and towards a group of about eight men huddled around a seaman sitting on the deck clutching his knee and rocking back and forth in pain.

The group lifted the injured man onto a Stoke’s litter and carried him aft towards the fantail and out of the burning hot sun, just as I came along side in the whaleboat

‘OK…what the hell happened THIS time Mr. Jones?’ And like the time before there was no immediate answer to the Captain’s question.

The Engineers had been working for several hours on the windlass. They had disengaged the wildcat clutches and filed the arc burns off breaker contacts, were ready for a test, and called for Mr. Jones to come and operate the controls.

“Don’t you dare touch a thing, Mr. Jones, I’ll do it myself” The Captain charged in front of the mate, beating him to the controls, and then called out, “Is everyone clear?” He pushed the lever forward and the entire geared mechanism jumped to life. The Captain engaged the wildcat clutch and had the crew release the chain grabber, then turned the clutch lever to haul in the chain and anchor. It performed like new and in no time the anchor was secured and the ship was on its way again. There was no further exchange between the Captain and Mr. Jones…at least within my hearing.

Later, while slowly powering along the coast of a plush green island, we saw a lot of activity as men scurried around on the beach. A yellow flare suddenly arched above the palms. Several amphibious trucks drove into the water heading out towards the ship.

An upset Major was barking out orders that were partially drowned out by the noise from the exhausts of the Alligators as they approached the ship. “God dammit! I told y’all to anchor close to shore! There=s plenty of deep water right up to the beach!”

“Come aboard Major…we’ll discuss the plans for off-loading.” The Captain was red-faced with fury as he bellowed over his hailer at the approaching officer.

“We don’t have time to waste talking,” growled the Major in a heavy southern accent. “Move in towards the beach and start loading those supplies on our trucks…and I mean now! We’ve been waiting three days too long already.”

The hatches were opened and the first things to go into the amphibians were large heavy tents with red crosses on white backgrounds. One tent almost swamped the first amphib that had the loud mouth Major aboard and that set him off yelling again.

“We don’t want those damn hospital tents,” he screamed, reversing the loading process, “load ‘em back aboard and start unloading the Quartermaster supplies.”

“Major…for your information,” the Captain bellowed, “we don’t have any Quartermaster supplies…. we are hauling bombs that were destined for the airstrip at Tacloban and to get to those damned bombs we have to offload the hospital gear first…do you understand? If you want to discuss this further I suggest you come aboard and read my orders!”

The Major jumped to an empty Alligator, came along side and climbed aboard. Ignoring everyone and everything, he bulldogged his way up to where the Captain was waiting on the bridge-wing and without a hello or introduction grabbed the papers out of the Captains hand.

“Who the hell authorized these?” The Major arrogantly demanded from the Captain as he tried to make out the hen scratches for the signature on the mimeograph that had huge ink smears in the typed title area under the signature.

The Captain looked around at Mr. Jones and asked, “Who gave you these orders?”

“A Transportation Officer at the Harbor Master’s shack,” he replied and after a moment of thought added, “I think he was a 1st Lieutenant. He handed me a sheaf of orders and charts. He said that since I was now assigned to the ship that I was to take the package and deliver it to you.”

The Captain re-read the typed form page, where it said vessel, it said was very clear but the smudged mimeographed copy typed insert was hardly distinguishable. On closer examination an F and a P could barely be made out but the number was little more than a blob.

“And you, Captain, sailed your ship here where there is no airstrip, knowing you had bombs for the Air Corps…and said nothing!” The Major was practically foaming at the mouth. “I’m recommending that you be relieved of command and that your next officer in line take over! I am radioing my divisional headquarters to that effect when I return to my field post.”

“And I,” the Captain growled, nose to nose with the Major, “am ordering you off my ship. I’ll not listen to another word…leave now, or I’ll have you thrown overboard!”

Seeing his one chance to have a command handed to him disappear, the 1st Mate, to the Captain’s astonishment, sided with the Major saying, “Captain, I think you’d better listen to the Major and not do anything impulsive.”

The Major spun around and departed the ship, ordering no further discharging of cargo. He rounded up his six amphibs and took off towards shore at a high rate of speed as if they were invading a hostile enemy beach.

“Mister JONAH,” the seething Captain said in a low subdued voice, “I wish to speak with you privately in the chartroom.” He then turned to me and ordered, “Clear the bridge and see that no one disturbs us. Mister Jones and I will be tied up.”

“Yes sir.” It was all I could think to say, but the pursed lips and grim look on the Captain=s face spoke volumes.

Their conference lasted about an hour. The Captain retook the watch and relieved me to go to dinner. The 1st Mate did not show up for dinner and I was besieged by the officers and crewmen to explain what was going on. I said nothing, as I wasn’t sure just what was going on either. Listening to the scuttlebutt was like listening to a bunch of old women at a quilting bee, but one thing that was mentioned over and over again was the reference to “Jonah”, a name seaman frequently associate with a person of ill omen aboard ship. This was in reference to the character in the Old Testament and the whale incident when God blew up a mighty storm because Jonah refused to obey God’s command to go and do his bidding and the crew, believing he was the cause of their turmoil, threw Jonah overboard.

Nothing was officially said. The Captain and I stood six by six hour anchor watches and I took it that Mr. Jones was relieved of his duties. Everyone aboard ship spent a restless night.

The next morning, the deck crew had no sooner uncovered the hatches when it started to rain hard and they had to hurriedly re-cover them. Since most of the crew was already soaked they stayed topside taking advantage of the freshwater showers. Suddenly the rain quit just like it had started, leaving several men fully soaped with no way to rinse off other than to dive over the side, with the Captains approval of course, or to douse themselves with a bucket of salt water.

The roar of a lonely amphib could be heard as it worked its way out towards us. As it approached I thought that this, because of the Major’s threat, could a moment of serious consequences for the ship and, or, the Captain. Being so apprehensive, I went up to the bridge and pretended I was busy in the chartroom, thinking that it would be the best place to overhear anything that might transpire.

The Captain had the Army’s “Ship and Gun Crew” man the rail, in their khakis, hoping that their military presence might lend a bit of dignity to the occasion.

It must have made an impression. The Major and a Captain boarded and when they saw the uniformed GI’s at the rail, came to attention and saluted. They requested to meet with the ship’s Captain. A Tech. Sgt. responded with, “Follow me sir’s,” and led them up to the bridge.

“Good morning Captain,” said the Major, “may I introduce my Staff Officer, Captain Randel. I believe apologies on my part are in order for my short-tempered display yesterday. I do apologize. Captain Randel informed me on my return to the beach that we are to receive and set up a Field Hospital being transferred up from New Guinea. Another ship resembling yours was due yesterday with the Quartermaster stores. I regret if I caused you or your crew any unpleasantness.” After saying his piece he saluted our Captain, turned on his heel and with his Aide at his side started to leave the bridge without waiting for any response from the Captain.

“Hold on there ‘Mister’ Major! Your tantrum yesterday was the cause of destroying my First Officer=s career…I intend to hold you accountable when my ship returns to Tacloban. Now sir…you are free to go.”

The Major slowly turned around, and then froze. I got the impression that he was in a state of shock and couldn’t find the right way to respond. The surprised look on his face clearly showed that he had never been taken to task like this before, especially by a civilian. In his previous actions his demeanor had appeared to be resentful of having to deal with anyone below his station or not GI, and he now found himself at a loss at having to respond to being humiliated and dismissed by a “civilian”…and in the presence of others.

“Captain…may I…ah…again offer my apologies. Is there any way in which we may reach an amicable solution to your First Officer=s dilemma? Surely you can find it in your heart to forgive your…‘Officer’…for one slight indiscretion?” The Army Major extended his open hands in a final display of appeal and then, seeing no change of emotion on the ship Captain’s face, slowly left the bridge and departed the ship; an obviously tormented person.

It took the rest of the day to off-load the tents and medical equipment because the amphibs could only haul small loads without nearly setting them awash in the choppy waters.

Just as darkness was taking over, a gray painted FP boat appeared from out of nowhere; she was almost identical to the green painted Army vessel. It was obviously manned by a Coast Guard or Navy crew. She approached close aboard and hailed over her PA system asking how the bottom was for anchoring and if currents were severe.

“You’ll find plenty of water and a good bottom as close as 75 yards off the beach but you’re welcome to side-tie with us for the night,” the Captain offered. “We already have fenders and planks over the side to keep the amphibs from banging us up”.

“Will do…and thanks for the invite,” responded the person on the bridge without using the hailer. His men put over their own fenders as others passed over mooring lines and in no time the two vessels were secured together.

We had previously been informed that this particular area had been recently secured from any major Japanese threats. Only the larger islands in this group were invaded and many of the smaller ones were by-passed. Frequently out of desperation the enemy die-hards would take pot shots at passing vessels, then quickly evaporate back into the jungle.

As badly as the Major needed or wanted the stores ashore he didn’t want to expose his amphib-drivers to any harassing enemy fire while under lights, so we didn’t unload at night. I had the early night anchor watch (6-12) and went to wake the Captain for watch at 23:30. Getting no response from my call, I pounded on the door, but still got no answer. I then went to the Chief Engineer’s cabin and asked him to go into the Captain’s cabin with me. We tried knocking and yelling to no avail. The Chief kicked out the lower door panel, reached in from underneath and unlocked the door.

We found the Captain delirious and shaking violently. He was lying in a sopping wet bed, barely alive, from what appeared to be a massive malaria attack. The whole crew soon became aware of the problem. They brought up another mattress and several of the men transferred him to the dry mattress, then covered him with blankets and tried to force him to drink water while downing a hand full of Atabrin tablets.

Being concerned for the Captain=s situation, I went over to the Coast Guard vessel and asked the skipper, a CWO, if he had a medic aboard. They did and a man was sent to treat our skipper and stayed with him for most of the night.

After counseling with the Chief Engineer over the 1st Mate’s situation, we agreed that for the safety of the ship the Mate should resume his duties without any conditions attached.

The 1st Mate was asked to come to the Chief Engineer’s cabin for a conference, the problem was laid on the table and we all agreed it was the proper procedure.

Mr. Jones took the watch at 03:30, but before going below I entered a whole page of detailed events in the logbook and again, at the top of the page, added in capitol letters FRIDAY then signed it. While browsing the previous page I saw the statement, “Mister Jones, First Officer, relieved of duty this date. A Letter with details will follow,” The Captain’s signature was scrawled below.

After breakfast in the morning the Chief and I were left alone at the table. I asked him if was aware of the Captain’s superstitions and he acknowledged that he was, but considered the captains idiosyncrasies a form of personal entertainment and did not take them seriously.

The crew began shortening the scope of the anchor chain as the Coasty ship slipped her lines and moved closer inshore to anchor. They said that they had taken aboard much of the hospital equipment at Finschhafen a week before, but they were routed around Mindanao and sat there waiting out the storm that just passed through here.

The Coast Guard corpsman medicated and stabilized our Captain. The shaking came and went, as did the fever, for the rest of the night and as there was no hospital or landing strip near by, we decided to return to Tacloban according to our sailing instructions and to finally off-load the fin-less bombs.

Mister Jones, now in command, decided to go ashore to get signatures from the Major, accepting delivery of our cargo. Some of the crew thought it was just an opportunity for him to flaunt his new authority. On his return, he ordered sea watches set and the ship prepared to get underway.

Standing, 6 on and 6 off, watches wasn’t too bad because all the maneuvering through the straits kept everyone on their toes. After anchoring at Tacloban a launch came along side and took off the sick Captain. A short while later the launch returned with the Port Captain and some Army Officers and asked for all ships Officers to report to the bridge.

On my arrival on the bridge I was asked to inspect the logbook. It appeared that a page was sliced out as close to the book bind as possible by a razor and I was asked if I knew anything about the page that was removed. I was dumbfounded because the missing page had been there when I had entered my watch activities in the log at 0600 when I was relieved.

I thought that the only one to profit from the page’s removal would be 1st Officer Jones…now the acting skipper. Turning to the Chief Engineer I asked if he knew anything and he denied any knowledge of a missing page. Mr. Jones appealed to everyone in the wheelhouse, protesting that he knew nothing of the missing log page.

“Does anyone know or remember what was written on that page?” one of the Army Officers asked.

We all stood quietly, not wanting to commit to answering such a pointed question. We all knew what was entered on that page but none felt it was their place to volunteer such an incriminating piece of information. All eyes turned to Mr. Jones as we stood there silently.

Mr. Jones sensed the men’s stares on him like hammers pounding on his body. He blurted out, “I don’t think it’s a secret that I was relieved from duty…it was entered into the log…but that certainly doesn’t mean I removed the page!”

Several days later, I was relieved by a superior Mate and sent ashore to await a passage home, for I just completed another contract.

I went to the field hospital to say my good byes to the skipper only to learn that he was being ordered stateside out of the high humidity because of the severity of his illness, and was scheduled to leave in a day or two.

The Captain confided in me, “I was questioned by the army brass about the missing log page and got the impression that Mr. Jones had led everyone to believe that I had cut it out…but you and I know I didn’t…isn’t that so?” The tone in the skippers question was not that of a challenge or requiring an answer but one of seeking to confirm his personal deductions. Then after a pause he added, “after having this time to digest all the circumstances I believe that whoever destroyed it did the right thing.”

I remember the Captain telling me that he was a commercial fish boat skipper before World War II. He was a great storyteller and it seemed to amuse him to tell of old sea-going superstitions while standing watches or at mess. What was so intriguing was that the crew thought the Captain actually believed his own tales. He had a knack for applying folklore, tradition or superstitions to almost every incident, as circumstances would occur.

I never saw him read the bible nor heard him quote passages. I did find out that he was a Slav from the old country and was brought to the United States with his family as a youngster. That, no doubt, accounted for his old world eccentric superstitious nature.